***

Since its release in the mid-nineties, I had always intended to read ‘Infinite Jest’, the Seinfeldian(1) epic of biblical proportions by David Foster Wallace. With twenty years having passed since its publication, I have only just found the time and the mental capacity to absorb it, after three unsuccessful attempts. Written between 1993 and 1995, long before the societal scars of 911 turned the United States of America against its own professed values, this dense tome has been lauded as a ‘post-’ whatever masterpiece. (Sorry, but when someone informed me that the book was ‘post-whatever’, my brain began to auto-cannibalize and refused to function again until that person was at least three nautical miles from my location.) As a shorthand, for those who don’t know what it means, “‘post-’ whatever” means that in short, the terrorists get what they want, and the two protagonists are incapacitated.

At one time, a story like this would have been considered the stuff of pulp science fiction, but it can now pass as serious literature, even to the point of being studied exhaustively by sage professors at prestigious universities. This is a trick pulled off only by the immense talents of the likes of Atwood, Vonnegut and (more than a century and a half ago) Mary Shelley. The fact that Infinite Jest is also a broad farce on the level of Cervantes seems oddly irrelevant in this context as it gleefully breaks the unwritten ‘rule’ of American literature, that serious books must be serious. Ignoring conventional story structure, Mr. Wallace jumps around his story creating what he described as a ‘fractal’ pattern of self referential sequences that reflected the whole. To say this made the story a little hard to follow would be an understatement. Multiple readings might well reveal the structure he described, but multiple readings of a 1000 page book(2) is a lot for a writer to ask, though in this case it might be worth it, if only as an intellectual challenge more than any intense interest in whatever meaning the story might hold.

“The truth will set you free, but not until it is finished with you.”

— David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest

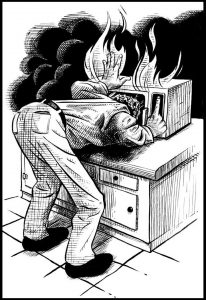

The novel takes place in a semi-fictional mid-2000’s Boston, but is clearly a reflection of pre-911 America that only exists now in the minds of people who’s already limited optimism was crushed by the election of George W. Bush and what happened afterward. I have to admit I never clearly figured out many of the actual dates Mr. Wallace intended these events to take place, and, based on some interviews, neither did Mr. Wallace. Whatever the case, it seems to make sense if you don’t examine it too closely. It tells the story of an exceptional family, and the exceptional people who surround them, all of whom are spectacularly incapable of achieving anything of significance as the result of their exceptionalism. The plot centers around something called ‘The Entertainment’, a Hitchcock inspired MacGuffin created by the family’s auteur-filmmaker patriarch just before exploding his own cranium in a specially rigged micro-wave oven. (I’m still not certain if this was supposed to be a performance art piece or a simple act of despair, but I’m fairly certain that Mr. Wallace had absolutely no interest in clarifying for the reader which it might have been.) To say that the Entertainment was effective in its titular purpose could only be described as an understatement, even to the point that an individual viewing this  Entertainment would endlessly avail themselves of it, forgoing food, water, sex and any other stimulation until, eventually, they die. The viewer’s brains are somehow directly stimulated by this eye candy in such a way that it induces an irrecoverable addiction to the brain’s own chemicals. Withdrawal from the Entertainment induces a psychotic meltdown that can only be satiated by The Entertainment itself. It leaves the victim in a catatonic state that s/he cannot wake from until s/he finally dies of starvation or insanity or immobility in general. The Entertainment is the logical progression (ad absurdum) of the American ideal of the pursuit of happiness. What this video ‘cartridge’ contained, Mr. Wallace never tries to explain, but as a metaphor for drug addiction, it is a brilliant notion. (It also satirizes American obsession with television, taken to its logical extreme.) Quebec Separatists intend to weaponize this Entertainment as a blackmail tool to allow the Province to secede from the oppressive control of the united government of North America. (The Organization of North American Nations (O.N.A.N), a unification instigated by some vague environmental catastrophe (called the Great Concavity from the American point of view, the Great Convexity by the Canadians) that rendered New England and parts of Quebec and New Brunswick inhabitable, useful only as an oversized toxic landfill.)

Entertainment would endlessly avail themselves of it, forgoing food, water, sex and any other stimulation until, eventually, they die. The viewer’s brains are somehow directly stimulated by this eye candy in such a way that it induces an irrecoverable addiction to the brain’s own chemicals. Withdrawal from the Entertainment induces a psychotic meltdown that can only be satiated by The Entertainment itself. It leaves the victim in a catatonic state that s/he cannot wake from until s/he finally dies of starvation or insanity or immobility in general. The Entertainment is the logical progression (ad absurdum) of the American ideal of the pursuit of happiness. What this video ‘cartridge’ contained, Mr. Wallace never tries to explain, but as a metaphor for drug addiction, it is a brilliant notion. (It also satirizes American obsession with television, taken to its logical extreme.) Quebec Separatists intend to weaponize this Entertainment as a blackmail tool to allow the Province to secede from the oppressive control of the united government of North America. (The Organization of North American Nations (O.N.A.N), a unification instigated by some vague environmental catastrophe (called the Great Concavity from the American point of view, the Great Convexity by the Canadians) that rendered New England and parts of Quebec and New Brunswick inhabitable, useful only as an oversized toxic landfill.)

Half the story centres around the Enfield Tennis Academy, founded by the Entertainment’s filmmaker, James Incandenza, Jr., for the benefit of his sons, who were mildly talented tennis players. (It seems an elaborate edifice for such mediocre players, though I’m willing to concede that I may have missed the real reason why he might have built the place. I think it’s kind of irrelevant to the story anyhow.) The Incandenza’s dysfunctional family relationship, designed to reflect the familial bliss of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, filters down into the lives of the students of this fictional New England private school, where the students are subjected to the many Shakespearian-level mental problems of the staff.

The other half of the story centres on Don Gately, a brutish blockhead suffering from drug addiction and far too many blows to the head playing junior football, a man who accidently killed the leader of the Quebec Separatists using snot. (I would try to explain this but, like everything else in this book, it’s a very long story that Mr. Wallace tells better than I could ever hope to.) With no capacity to find his own course, Gately’s only redeeming feature seems to be his unreasoning loyalty to people who don’t, in any way, deserve it. He doesn’t find out until it is too late that happiness is brief, transitory and meaningless, and its endless pursuit is ultimately self-defeating. A recovering drug addict, he runs a drug addiction facility that many of the main characters end up gravitating to by the end of the book. (Which isn’t actually the end of the story but only somewhere in the middle. Hey, I warned you about the ‘post-whatever’ stuff.). A weird combination of events (again, a long story) eventually brings the wheel-chair bound Quebec Separatist Assassins (again, a long story) to his door where chaos ensues and he ends up in the hospital. This is where Mr. Wallace (with only some success) tries to tie up the flailing ends of his story. Much has been said about Mr. Wallace’s decision to end the book in what appears to be the middle of this hopelessly circular story, but I happen to agree with his decision to end it there. It was the only place where all the disparate elements converged, and one of the few places he would have had any hope of wrapping everything up, which he almost succeeds in doing.

“And when he came back to, he was flat on his back on the beach in the freezing sand, and it was raining out of a low sky, and the tide was way out.”

— Last line of INFINITE JEST, David Foster Wallace

One of the quirks of Mr. Wallace’s writing is his copious use of footnotes and endnotes, many of which could have been easily incorporated into the text in a more fluid manner. (Granted, that would have made the book even longer than it is.) Mr. Wallace contends this was a deliberate attempt to fracture the already well fractured narrative. (It should hardly be a mystery then why I repeatedly kept asking myself, even after passing page 500 and with more than half the book to go, why I was even reading the damn thing.) But even making allowance for his style, there were certain things could have been referenced much earlier, making the premise much easier to grasp, while maintaining the reader’s will to continue, which I found continuously challenged. This unnecessary confusion is most evident in the brilliant (but slightly over-used) satirical premise of the corporate sponsorship of each calendar year, which is presented not unlike Chinese Astrology where instead of the ‘Year of the Rooster’, it becomes ‘Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment’ and, given capitalist America’s penchant for excess, this inevitably leads to the ‘Year of the Yushityu 2007 Mimetic-Resolution-Cartridge-View-Motherboard-Easy-To-Install-Upgrade for Infernatron/InterLace TP Systems for Home, Office or Mobile’ by people who didn’t really understand the concept. But Mr. Wallace chose not to explain any of this until more than three hundred pages in, which made it difficult to keep track of what was taking place in the past or the present, a bit of a problem since the story is being told non-sequentially.

There are many of these ambiguities that are never clarified. For instance, the ghostly wraith who moves furniture, tortures some of the students and bothers Gately’s recovery from his gunshot wounds near the end of the book is almost certainly the ghost of James Incandenza, Jr., and it seems he is firmly tied to his son, Hal. If Hal was the patient in the bed next to Gately near the end of the book, and he knew where his father’s head was buried, then it makes sense when they, along with Joelle, dug up his father’s head looking for the ‘Master Copy’ of the Entertainment with the double agent John Wayne, only to find out about his brother Orin’s treason. (That seems to almost makes sense, doesn’t it?) So that means James Incandenza, Jr. (through Hal) was perpetrator of the pranks that the book attributes to the wraith, which makes the first chapter fall into place, the result of his addiction to Pemulis’ stash of super-powerful drugs that had been hidden in the old shoe in the ceiling, which Hal seems to know is there but Permulis never suspects him of indulging in. (Hal’s excursions into the lower areas of the ‘lung’ to smoke ‘pot’ seem to me to be overblown, as is his need to seek help at the addiction centre for dependence on it. I’ve heard of some powerful strains of pot in my day, but his reaction to it is something out of Reefer Madness, in other words a substitution for the substance he is really taking down in the ‘lung’. Or maybe I’m completely wrong about that, too.) In other words, I suspect that the author himself might not be very reliable as a witness to the events in his own book.

David Foster Wallace On Infinite Jest

And these are hardly the only questions that don’t get clarified by the end of the book (or the middle of the story, whatever you prefer). There are seemingly huge questions that never get answered in anything near a satisfactory manner. Was Hal’s mother a Quebec spy? (Probably.) Did she know that her student lover, John ‘No Relation’ Wayne, was a double agent? (Who knows?) Was Hal’s mental disability at the beginning (ie: the end) of the story self inflicted? (Almost certainly given the theme of the story.) Did Hal kill his own father and hide the master copy of the Entertainment in his decapitated skull? (Who knows, but he did seem oddly unaffected by his discovery of his father’s decapitated corpse.) Then there’s Mario, the cartoonishly handicapped middle child who makes laughable documentaries of the situation the great man ‘Himself’ left behind in the wake of his suicide. Is he even James’ son, or did the ‘Moms’ have an affair with Charles Tavis, the man who took over the Academy after that unfortunate death? (Again, who knows?) And did Orin, the oldest son, betray his country under torture? (Absolutely) Was his Orwellian bug-infested torture chamber real, hallucinatory or symbolic? (Who knows? But being trapped inside an enormous drinking glass while suffering detox would be pretty emblematic for an alcoholic.) Was the Entertainment itself symbolic? After all it remained (literally) inside its creator’s head even after his death. (Who knows?) Then there’s Joelle Van Dyne, radio phone-in mystic and principal actor in the lethal ‘Entertainment’, who has destroyed the lives of everyone she has been involved with, including the almost the entire Incandenza family. This woman causes irresistible obsession in men even when unseen and anonymous on a late-night radio programme, much like the drugs that have caused such harm to the people surrounding her. (In the absence of drugs, Gately chooses her as a substitute obsession.) Was Joelle actually deformed by a parental acid attack or does she wear the veil to protect herself and others from her lethal beauty? (Who knows? She calls this her ‘deformity’, but I can find little evidence anything physical happened to her appearance, which was remarkable enough to earn her the label of P-GOAT, the prettiest girl of all time.)

“She had a brainy girls discomfort about her own beauty and its effects on folks.”

― David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest

These questions, as well as hundreds of other loose ends, didn’t seem important enough for Mr. Wallace to feel the need to clarify, as well he shouldn’t have. Such speculation, even by the writer, would be endless. Most things in life have no explanation worth investigating, even less so in a novel as deliberately convoluted as this one. It seems a shame to have hidden such brilliance in opaque prose and confusing structure. For whatever reason, it seems Mr. Wallace couldn’t or wouldn’t avail himself the services of a good editor, though I’m told the editor of Infinite Jest was one of the best in the business. As a result, a lot of stuff gets lost in the tangle of mundane details that seem ultimately irrelevant to the actual story, which itself becomes an intentionally narcissistic bit of mental calisthenics by the author. I do understand that the self-involved nature of the author is self-consciously reflected in the self-involved nature of the characters, and Mr. Wallace is using this as a premise for their downfall. The pursuit of pleasure to the point of death, the ultimate fallacy of the endless pursuit of happiness. Was Mr. Wallace predicting his own downfall? Was it a cry for help? (He committed suicide in 2008.) If suicide is seen as the ultimate in self-involvement, then the deaths caused by the Entertainment (and drugs) could only be seen as such. Greater minds than me have speculated endlessly on this with little to show for it.

“I read,’ I say. ‘I study and read. I bet I’ve read everything you’ve read. Don’t think I haven’t. I consume libraries… I do things like get in a taxi and say, “The library, and step on it.”

― Hal Incandenza, Infinite Jest(David Foster Wallace)

I believe Infinite Jest is, above all, a story about dependence in all its forms, not just addiction. While a large part of the story takes place in an chemical addiction facility, the overall story seems to be about what happens when dependence fails you, and how much worse it would be if it ultimately didn’t. Dependence on other people to define your own existence is something that perpetuates endless human suffering not just in America, but everywhere, whether that dependence is about mindless entertainment, drugs, sports, a parent or some other human savior, all of which inevitably and eventually let you down. We’re all addicts in rehab simply substituting one form of dependence for another. This book presents an absurdist view of American class and privilege and  how ultimately meaningless it all is. The book brilliantly exudes a clear sense of the narcissism of America during the period it was written, shades of the self-aggrandizement that would lead to the election of George W. Bush and the creation of the oversized SUV (and all that implies), where Bill Clinton’s message that ‘it’s about the economy, stupid’ was distorted to its ridiculous extreme and the artificial pumping of money from the pockets of the poor to the pockets of the rich escalated to a frightening scale, interrupted (or perhaps accelerated) only briefly by the distraction of the 911 attacks. With everything that has taken place since the publication of this book, it inadvertently creates a strange mirror image of our world, an alternate present day that seems remarkably accurate and at the same time, completely foreign. No cell phones, much less hand-held computers. Television ‘cartridges’ instead of the digital universe. Terrorists as only peripheral, small scale threats. Drugs that seem tame in the face of synthetics like carfentanil. ‘Entertainments’ designed to directly effect our individual minds without our knowledge, somehow seem much less frightening than secret algorithms designed to effect entire populations and influence elections. This world Mr. Wallace describes is a good illustration of how tame are nightmares can be when compared to reality.

how ultimately meaningless it all is. The book brilliantly exudes a clear sense of the narcissism of America during the period it was written, shades of the self-aggrandizement that would lead to the election of George W. Bush and the creation of the oversized SUV (and all that implies), where Bill Clinton’s message that ‘it’s about the economy, stupid’ was distorted to its ridiculous extreme and the artificial pumping of money from the pockets of the poor to the pockets of the rich escalated to a frightening scale, interrupted (or perhaps accelerated) only briefly by the distraction of the 911 attacks. With everything that has taken place since the publication of this book, it inadvertently creates a strange mirror image of our world, an alternate present day that seems remarkably accurate and at the same time, completely foreign. No cell phones, much less hand-held computers. Television ‘cartridges’ instead of the digital universe. Terrorists as only peripheral, small scale threats. Drugs that seem tame in the face of synthetics like carfentanil. ‘Entertainments’ designed to directly effect our individual minds without our knowledge, somehow seem much less frightening than secret algorithms designed to effect entire populations and influence elections. This world Mr. Wallace describes is a good illustration of how tame are nightmares can be when compared to reality.

“That everyone is identical in their secret unspoken belief that, way deep down, they are different from everyone else.”

— David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest

I think science fiction can be defined as a medium of ideas and Infinite Jest is absolutely brimming with ideas. The book is very funny at times, mostly as a winking parody of James Joyce and his stream of consciousness techniques superimposed over a wacky world of distorted, frighteningly realistic characters. But it works only if you’re able to endure the intellectual exercise Mr. Wallace sets out for you. I liked the book in the end, but I couldn’t help but feel that a funny novel about addictive entertainment should have been more, well, entertaining.

***

(1) – The book was published at the height of popularity for the TV show Seinfeld, notoriously a ‘television show about nothing’, which this seems to be, at least on the surface.

(2) – That’s right, more than one thousand tight, dense pages, not including (what seems like) hundreds and hundreds of pages of endnotes that I had absolutely no interest in reading.*

* It has been suggested that reading the end notes is essential since they explain some of the ambiguity of the story. But if such a thing is really necessary, has the story really succeeded?**

**Yes, I am referencing something irrelevant to my story in a footnote within a endnote in a self-consciously ironic way. This meta-ironic cynicism is boringly common today, but was hardly known back when the book was written. It would be overstating it to say that Mr. Wallace popularized such a thing, since it isn’t (and has never been) particularly popular.

***

1,995 total views, 1 views today