Robert Pirsig and The Corrosive Effect of Dualism

“Making… an art out of your technological life is the way to solve the problem of technology.”

— Robert M. Pirsig, (Interview, NPR, 1974)

***

Robert Pirsig died today.

For those who do not know who Robert Pirsig was, it might be difficult to describe how much of a profound loss this is. Personally, it would be hard to explain the effect this man had on my life, though I never met him, knew little about his personal life, nor did I even know what his voice sounded like until recently. But, as an intellectually starving child of fifteen, surrounded largely by uneducated, uninterested people in a small rural town, his voice came to me with such clarity, I cannot even begin to describe its effect. His magnum opus, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, essentially one long essay thoughtfully disguised as an entertaining novel, allowed me to see the world in a wondrous way. If I had not heard his wisdom through his simple words, I don’t know how I could have survived.

I wish I still had that particular copy of that wonderful book but it was worn to nothing. The dust cover was missing, pages yellowed and annotated, spine split and hanging on only by a few bits of string. Having read the book two more times in the following two years, I discarded the battered grey hard cover in favour of the famous pink cover of the Bantam Paperback edition just before I graduated high school. I was the first of my family to go off to College, a hopeless endeavor doomed from the beginning due to the lack of funds and the limitations of a rural high school education. What Robert Pirsig showed me was that I wasn’t crazy. That I didn’t have to think like everybody else. The idea of working yourself to death until you retire has been shown to be the myth that it always was, and the quality of each moment is far more valuable than the mythical ‘life of leisure’ that had been promised our parents. That world, the one in which Mr. Pirsig wrote Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance,

was a short lived aberration that no longer exists.

“We’re in such a hurry most of the time … a kind of endless day-to-day shallowness, a monotony that leaves a person wondering years later where all the time went and sorry that it’s all gone.”

— Robert M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

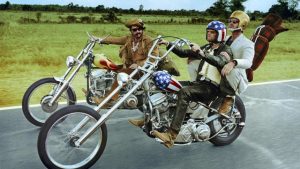

It was unfortunate that Mr. Pirsig’s voice was largely unheard in the din of the counter-culture movement of the 1960’s and 70’s, because he foretold the world we live in today, where we have become slaves to our own technology because we haven’t the faintest idea how it all works. Pirsig never rejected western culture like the hippies did during the counter-culture movement of the time.He thought the movie “Easy Rider” was an prime example of an impractical view of our technological society, pointing out, correctly, that Wyatt (Peter Fonda) and Billy (Dennis Hopper) would have never made it out of Southern California, simply based on the size of their engines in relation to the size of their gas tanks. It’s the sort of practical thinking that separates the counter-culture from what Mr. Pirsig was trying to communicate.

Persig suggested Easy Rider spoke to the impracticality of the hippy movement. He understood that these people were trying to run away from themselves, instead of embracing what they were – human animals, multi-faceted organisms that uses logic and spirituality in tandem to create a world of wonders of our own making. He certainly didn’t see quality in the Harley Davidson motorcycles of that era, he saw it in the Honda CB77 Super Hawk, a motorcycle with only a 300cc engine, but which ran comfortably and reliably for long periods, something he knew he would never experience on a Harley.

“On a cycle the frame is gone. You’re completely in contact with it all. You’re in the scene, not just watching it anymore, and the sense of presence is overwhelming.”

— Robert M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

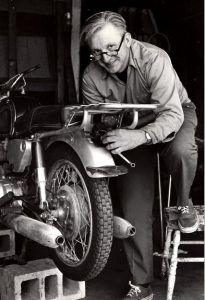

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance showed the world a different kind of counter-culture. Something that didn’t need to reject technological society but could embrace it. That the spiritual didn’t lie outside us, but within every mundane task we perform every day. It didn’t matter what task, only that we strived to find the highest quality in the moment as we perform it. That even something as logical and mechanical as the repair and maintenance of a motorcycle had an essential spiritual aspect to it that could not be ignored without risking catastrophic damage.

“And what is ‘good’, Phaedrus? And what is ‘not good’? Need we ask anyone to tell us these things?”

— Robert M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Robert Maynard Pirsig was, literally and by all definitions, a madman. Clinically insane. Paranoid schizophrenic. Manic Depressive. Possibly bipolar. Institutionalized and brutalized with electroshock therapy until he was irrevocably changed, he lived most of his life in self-imposed isolation. His engagement with reality could only seem tenuous to anyone whose connection to the universe was through conventional ideas of a person’s place in the world, especially when compared to the world as it was in the late 1960’s in America. And yet, in that brief period of time when he could still clearly remember his pre-treatment self (who he called Phaedrus(1)), he wrote two startling books, stories about the world as seen from the point of view of someone who was, literally, mad. Mr. Pirsig was as complex a man who has ever existed, and it might be another generation before we see the likes of him again.

Other than being white men of European descent, I can think of little that Mr. Pirsig and I had in common. He was an extremely intelligent, highly educated man(2) who had relative wealth and means, access to resources I could never have dreamed of as well as access to intellectual capital that I had no way of knowing even existed. He arrived at his skewed view of the world through war and travel to foreign lands that I had only the vaguest idea of. And yet his conclusions of what he had learned set themselves into my mind with an ease that couldn’t be compared to any other teacher I have ever known. On hearing his thoughts of the world and what ailed it, few people have made as much sense to me.

In Hamlet, Rosencrantz laments the fact that Hamlet acts like a madman, and yet what he says makes logical sense, which suggests he’s far from mad. Every psychiatrist who examined Pirsig thought he was mad, and yet he wrote a book of such clarity that it was beyond anything they could have understood. A serious book, written in an unpretentious folksy style, discussing existential philosophy very much grounded to day to day consequence. His insistence that the Mythos of western culture, Jewish/Christian/Muslim philosophical theories based on the work of Aristotle and Plato, that divided logic and emotion into two separate, irreconcilable things, prevent us from seeing the world as it really is. That the idea of dualism is horribly wrong and that the problems of the world are caused mainly by that dualism.

The concept that Persig used to illustrate this idea was ‘quality’, a word almost everyone understands, and yet is virtually impossible to define. (Pirsig notoriously refused to even try.) A word that is directly translatable into virtually every language in the world, and yet is not satisfactorily defined in any of them.

“Any philosophic explanation of Quality is going to be both false and true precisely because it is a philosophic explanation. This is not because Quality is so mysterious but because Quality is so simple, immediate and direct.”

— Robert Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

For Mr. Pirsig, the only concept that seemed to fit his view of the world was the ancient art of Zen practice. Western culture, of course, saw, and still sees, Zen as some form of religion, but nothing could be further from the truth. If anything, Zen opposes all the concepts of western religion in favour of finding meaning in the fullness of everyday experience. The simplicity of being engaged with all your thought in the task at hand.

It seemed odd to me that this simple idea could be lost on most westerners, and everyone I knew who read the book found it impenetrable, complex and vague. I could see that the reason for all their confusion was they were looking for complexity where Pirsig was pointing out the underlying simplicity of it all. As I understood it, what he was describing was a form of practical spirituality, the idea that what made something practical, like maintaining a motorcycle, was also what made it spiritual, the elegant simplicity of how every part of the motorcycle worked, down to its smallest part. And how the complexity of the motorcycle came from the unification of those simple pieces, none being more important than the others, big or small. The chain of events that is required to make a motorcycle move forward under its own power is manifest in the spirituality of flying in two dimensions, which is essentially what riding a motorcycle really is.

“Zen is the ‘spirit of the valley.’ The only Zen you find on the tops of mountains is the Zen you bring up there.”

— Robert Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

The spiritual quality of that motorcycle ride can only be achieved through logical, mechanical processes of design manufacture and maintenance. The logical mechanical process that makes a motorcycle move does nothing to explain the purpose of the motorcycle. And at any point, if the process is neglected, even the smallest piece of that machine will cause the whole not to function physically, and at the same time preventing it from generating the spiritual expression for which it was intended. If the logical processes are neglected, the spiritual purpose of the motorcycle can never be achieved. And at the heart of it all, the concept of Quality, the process of making the ‘better’ choice on a moment by moment basis.

Spiritual contentment does not come from making the implicitly ‘right’ choice. Doing the ‘right’ thing without context is never the right thing. A series of ‘right’ choices can lead to disaster. And the primary reason for this is because doing the ‘right’ thing is external. It doesn’t come from the deep understanding of the relative quality of choices that need to be made in the larger context of the universe itself. Understanding this requires holistic thought, both logical and spiritual, since all the facts in the world will not help in the least unless those facts can be connected, woven into a process of thought that makes the universe understand itself.

“They associate metal with given shapes, all of them fixed and inviolable. (But) steel can be any shape you want if you are skilled enough, and any shape but the one you want if you are not. Hell, even the steel is out of someone’s mind.”

— Robert Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Someone couldn’t be expected to repair a mechanical system on a motorcycle unless they had a metaphysical understanding of what that system is designed to do. And that system itself could never have been conceived without a thorough spiritual understanding of what a motorcycle is meant to achieve. All the adventures of mankind have no meaning when humanity, spirituality and emotion are removed. And yet nothing can be achieved without logic and reason to guide the practicality of any decision. Both the metaphysical and practical value of the motorcycle can be nullified by the failure of even the smallest, most inexpensive part. A single tiny broken screw can obliterate the entire spiritual purpose of the machine, which is why the metaphysical quality of that screw must be as high as possible. It’s an easy concept to understand, but a difficult one to explain.

“… that the motorcycle is primarily a mental phenomenon.”

— Robert Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Pirsig’s idea that the overarching concept of quality, as he saw it, was the point where reason merged with spirituality, becoming one. Dualism is a two dimensional concept, where as quality, as he understood it, is three-dimensional, just like the world we all live in. Despite enduring since the time of Aristotle, dualism is surprisingly easy to debunk.

Love is not the opposite of hate. Indifference is the opposite of hate. And at the same time, indifference is the opposite of love. Does that make love and hate the same thing? Reason is not the opposite of emotion. Indifference is the opposite of emotion. Does that not make reason equal to emotion? I would hardly think so. This clearly shows that there is something wrong with the question. It was exactly this rejection of dualism that brought forth the Zen idea that one should not answer certain questions that presuppose dualism, refusing to answer either ‘yes’ or ‘no’, but ‘mu’, which means to ‘unask’ the question. A third alternative that rejects the basic prejudice behind the question. When applied correctly, the rejection of dualism in favour of a third alternative forces the divisions to disappear and opposing sides to evaporate, showing them for the arbitrary illusion they really are. Good versus evil. Love verses hate. Us versus them. Liberal versus Conservative. Thought versus action. War at great cost verses peace at any cost. None of these divisions actually exist except in the manner in which the questions are asked.

“Quality! That is what the Sophists were teaching! Not pristine ‘virtue.’ But aretê. Excellence.”

— Robert Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Every decision, if based on the overall quality of a situation, is the correct decision. Everyone understands on some level that emotion without reason is destructive, and reason without emotion is sterile. Passion coupled with reason creates wonders, and every great human achievement has been a result of the combination of both. Pirsig believed that nothing exists without this unified idea of quality and the value we place on that thing at any one time. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance was exactly as described: an inquiry into values. It was his way of explaining to us what he had discovered, that with the proper maintenance of mind, human values are far more prone to align than conflict.

So if Robert Pirsig was indeed a madman, then, like Rosencrantz, I find myself asking why it was he made so much sense. Could it be that he was the only one of us who was sane?

“Trials never end, of course. Unhappiness and misfortune are bound to occur as long as people live, but there is a feeling now, that was not here before, and is not just on the surface of things, but penetrates all the way through: We’ve won it. It’s going to get better now. You can sort of tell these things.”

— Robert Pirsig, Last lines of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

***

Robert Maynard Pirsig, Author

“Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values”

“Lila: An Inquiry into Morals”

Born: Sept. 6, 1928. Died: April 24, 2017

***

1) Phaedrus is a character in Plato’s Dialogue, based on an allegedly real Greek aristocrat who died around 400 B.C.E.

2) Pirsig had a Masters Degree in Journalism, studied Eastern Philosophy at Banaras Hindu University in India, and was a professor of writing and philosophy at Montana State and Illinois State Universities. Before electroshock therapy, his IQ had been measured at more than 170. His father, Maynard Pirsig, was one of the most celebrated Law Professors in Minnesota State history.

1,944 total views, 1 views today