STAR WARS AS RELIGION

An Essay, December 29, 2017

Since I was in grade school, Science Fiction has always been a big part of my life. From the age of fifteen until I quit University, I read as many as three to four books per week, most of them Science Fiction. My friends and I earnestly discussed the latest stories we’d found in novels and magazines, disparaging our other friends who read ‘stupid’ comic books. In 7th grade English, I infamously submitted a three page Science Fiction short story in lieu of my un-prepared-for mid-term exam.(1)

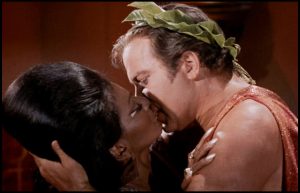

The first movie I ever saw in a proper movie house was Star Wars (wr./dir. George Lucas), and then after that, the unfortunately named ‘Star Trek: The Motion Picture’ (wr. Harold Livingston, Alan Dean Foster/dir. Robert Wise). Even today, I thoroughly enjoy reading a good science fiction story or seeing a good Science Fiction movie. The problem is, and has always been, that ‘good’ Science Fiction, in any form, is rare, and most of what I have read and watched on TV or seen in movies is embarrassing crap. (Star Trek, the original series is rightly known as one of the first smart Science Fiction television series, but also notorious for its lack of consistent quality.)

The problem is, and has always been, that ‘good’ Science Fiction, in any form, is rare . . .

There was a golden age of Science Fiction literature, of course, back in the 1930’s and early 1940’s, and, in film, the late-60’s to the early 80’s, when the technology of movie-making finally made it possible to properly visualize what these alternate worlds would actually look like. But for a few notable exceptions, those days are unfortunately long past. Science Fiction movies are notoriously difficult and expensive to make, which means there is little incentive to risk putting so much effort into something not everyone one wants to watch.

I can’t help but think it’s the result of studio executives who are completely mystified as to why these stories were popular in the first place. As a result, there seems to be a barren, meaningless quality to Science Fiction movies that makes me utterly disinterested in paying 12 bucks to see what ends up being just one more piece of corporate approved eye candy.

Some might argue that Science Fiction has become the biggest money making genre in modern cinema, but I want to argue against that point, or at the very least refine it. While the entire genre is notorious for the broad flavours of content under its umbrella, the common thread has always been what used to be disparagingly called a ‘morality tale’, a simple concept that held a deeper meaning in the real world. In all Science Fiction stories, the writer changes a few of the scientific rules of the universe, then speculates what human reaction and adaptation would occur as a result. ‘District 9’(wr./dir. Neil Blomkamp) and ‘Starship Troopers’, (wr. Edward Neumeier/dir Paul Verhoeven) speculated about the effects of a military reaction to alien contact. ‘Arrival’ (wr. Eric Heisserer/dir. Denis Villeneuve) and ‘Contact’ (wr. James Hart, Michael Goldenberg/dir. Robert Zemeckis) speculated how humanity might try to communicate with aliens. ‘Minority Report’(wr. Scott Frank, Jon Cohen/dir. Steven Spielberg) and ‘1984’(wr./dir. Michael Radford) speculated what would happen if our thoughts actually became criminal. ExMachina (wr./dir. Alex Garland) and ‘Blade Runner’ (wr. Hampton Fancher and David Peoples/dir. Ridley Scott) speculated about androids and artificial intelligence and how they would blur the lines of what it was to be human.

People don’t seem to understand that a movie like ‘Gravity’ (wr./dir. Alfonso Cuarón) isn’t really Science Fiction, even though there are space ships and other science trappings. Everything in that movie exists in the world we live in today, and so there is none of the scientific speculation inherent in what defines the Science Fiction genre.

Those who are not familiar with Science Fiction may not understand that there has always been a distinction between two broadly defined types of the genre; what I would describe as Speculative Fiction and Science Mythology. This split is easily illustrated by two benchmark Science Fiction institutions, Star Wars and Star Trek. Now, many could easily say there is little difference between the two series, but this could not be further from the truth. Star Trek was based on a humanist philosophy, where the fate of humanity is in the hands of humanity itself, surviving against the indifference of the universe using human innovation and adaptability. (A rationalist viewpoint.)

By contrast, the world of Star Wars is dominated by massive amounts of technology, but this harvest of human innovation is seen as the enemy of a residual faith-based belief in the divine. Essentially, it suggests that if we just close our eyes and believe in the ‘force’ (ie: God or a savior), then we will be saved. (A religious or spiritual viewpoint.) I think this delineation has always been present in Science Fiction, but it’s only in the last twenty years or so that there was much cross-over between the fans of one to the fans ofthe other. The primary reason for this would have to be large corporations who have wrestled control of these stories away from their creators and are now trying to manipulate the very people who made the franchises popular in the first place. Viacom, the conglomerate that owns Paramount Pictures and the Star Trek franchise, can’t figure out why it’s proving near impossible to massage their property into Star Wars levels of popularity, and the reason is obvious when you look at it from the religious/humanist philosophy of the two series. When their divergent philosophies are taken into account, it’s hard to imagine that any person who champions one point of view could have any patience for the other.

Viacom, the conglomerate that owns Paramount Pictures and the Star Trek franchise, can’t figure out why it’s proving near impossible to massage their property into Star Wars levels of popularity . . .

What I describe as Speculative Fiction has been described as Hard Science Fiction, but I feel that label sells short the creativity and humanity these stories can evoke. I don’t think Speculative Fiction is any more popular today than it was in its heyday. This is because it has a well deserved reputation for speaking truth to power, either through metaphor or sometimes even explicitly. (Star Trek was originally famous for putting subject matter on American television that would have not otherwise been tolerated.)

It is also rife with cautionary tales warning of hubris and the danger of uncontrolled technological development, not for the purposes of eliminating it and replacing it with religion, but to ensure such development didn’t cause the extinction of the species.

There are literally hundreds of very successful Speculative Fiction stories that have been made into entertaining movies with little or no spiritual aspect to them. I’m thinking, in no particular order, of movies like ‘Inception’, ‘Snowpiercer’, ‘Gattica’, ‘Twelve Monkeys’, ‘Alien’, ‘E.T. The Extraterrestrial’, ‘The Time Machine’ (1960), ‘Minority Report’, ‘Men In Black’, ‘War of the Worlds’ (2005)(2), ‘Invasion of the Body Snatchers’ (both versions), the ‘Back to the Future’ series, ‘Westworld’ (both versions), ‘Primer’, ‘Silent Running’, ‘Solaris’ (both versions)(3), the ‘Jurassic Park’ Series, ‘Tron’, ‘Planet of the Apes’, Frankenstein (pick one), ‘THX-1138’, ‘Brazil’, ‘Fahrenheit 451’, ‘Logan’s Run’, ‘The Fly’, ‘Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind’, ‘Dark City’, ‘Robocop’, ‘Wall-E’, ‘Outland’, ‘Predator’, ‘The Andromeda Strain’, ‘Moon’, ‘Dark Star’, the ‘Mad Max’ series and many, many more. These are all allegories for problems plaguing the modern day world, but set in the future or in space, or in another galaxy entirely. There are also great science fiction literary classics like Asimov’s ‘Foundation’ series or Larry Niven’s ‘Ringworld’ or Heinlein’s ‘Stranger in a Strange Land’ or Clarke’s ‘Rendezvous with Rama’ that have not been made into Science Fiction movies, despite the fact they are deservedly known world-wide as the best Science Fiction has to offer. In the context of the stories being told, there was little need for any sort of religious overtones in many of these stories.

Almost all the movies mentioned above have deep political, sociological and moral meaning, and though a few could be described as an unqualified success, most, however, were not financially successful, and some even bombed spectacularly when they were released in movie theatres. The reason could only be that these stories directly challenge the complacency of the movie-goer (and film studio executives, I suppose) who just want mindless entertainment. Few of these stories reflect well on the state of American materialism that has spread around the world, not to mention colonialism and the American government’s interference in other cultures. (I’m not suggesting that there haven’t been good movies made that criticize American culture, it’s just that they seem to be increasingly scarce in recent years.) Many regard Speculative Fiction as a cold, sterile Godless medium that can’t be reconciled with religious faith and it seems to gain popularity only as long as it doesn’t insult or criticize Judeo-Christian beliefs. But I feel Speculative Fiction can and should present spiritual concepts while also being critical of unquestioning religious faith.

There are movies, really good movies, where religious or spiritual stories are disguised as Speculative Fiction with great finesse, telling religious or spiritual stories that do not betray the scientific precepts in favour of unquestioning religious faith. For example, in ‘Blade Runner’, where human-like replicants return and demand answers from their God-like creator, only to be rebuffed. In ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’ (wr. Eduard North/dir. Robert Wise), where the Jesus figure comes to Earth and is martyred, only to rise from the dead and warn the world against its violent ways. In ‘Children of Men’ (wr. Sexton, Arata, Fergus, Ostby /dir. Alfonso Cuarón), where a miracle birth heralds the rebirth of mankind. In ‘Close Encounters of the Third Kind’(wr./dir. Steven Spielberg) where a man is tortured by visions and comes to understand the universe only once all is revealed to him. In ‘Ghost in the Shell’ (wr. Kazunori Ito, Shirow Masamune/dir. Mamoru Oshii) where the main character’s loss of humanity is only restored by her bond with a “ghost” living inside the machinery. Other really great examples of this include ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’, ‘Avatar’, ‘The Terminator’, ‘Cloud Atlas’, ‘Forbidden Planet’, ‘A.I.’, ‘Interstellar’, ‘The Fifth Element’, ‘Akira’, ‘Monty Python’s The Life Of Brian’(4) and many more. All of these stories are able to handle spirituality and religion within the context of the Speculative Fiction genre without subverting the humanist philosophy of its premise.

“. . . but I just hope the lad, now in his thirties, is not living in a fantasy world of secondhand, childish banalities.”

— Sir Alec Guinness

But it is when Science Fiction itself advocates for unquestioning faith and religion over humanist ideals that it becomes problematic. It’s a particular brand of Science Fiction that I find troubling, one in which the premise seems to advocate against the technological wonders humans have achieved, in favour of a primitive belief in the supernatural or the divine. This sub-genre, best described as Science Mythology, is willing to accept religious faith as a given, advocating for the idea that, no matter how much knowledge we gain, no matter how far we venture into space or into the human mind, our lives will never have meaning until we ‘accept’ God as our creator (whatever that means) and worship her/him unquestioningly.

What troubles me the most is that, unlike Speculative Fiction, Science Mythology has captured the imagination of this generation. There is little doubt that, as far as the general popularity of Science Fiction goes, Science Mythology has done most of the heavy lifting. It could hardly be seen as a coincidence that the Disney Corporation went to great lengths to acquire both Lucasfilm and Marvel. ‘The Avengers’ and ‘Star Wars’ will fit right in with Disney’s black and white version of the world as it ‘should be’, something that has always been the big winner when Americans get afraid and want to hide under the blankets and suck their thumb for a while. The thing about these Science Mythology stories, and their fatal flaw as far as I’m concerned, is their clear comicbook-level philosophical distinction between ‘good’ and ‘evil’, something derived from their mythological/religious roots.

One of the more successful illustrations of this peculiar sub-genre of Science Fiction would have to be ‘The Matrix’ (wr./dir. the Wachowski brothers), a more-than blatant retelling of the Christ story in a Science Fiction cloak. (The second and third films of the franchise are hardly worth mentioning other than to say that they were meaningless, betraying the potential of the first film.) Thomas Anderson (Jesus of Nazareth) is proclaimed ‘the One’ (the new messiah) by Morpheus (John the Baptist), who teaches him the ‘Way’. (John’s religion. Sorry, you have to read the bible to understand that one.) Anderson is deemed to not be the ‘One’ (a false messiah) by the Oracle (the religious establishment). He is then persecuted by Agent Smith (Pilate), who eventually executes him. Anderson is resurrected by his own force of will and becomes a God, Neo (The New Messiah), who will lead humanity out of slavery and oppression. (If all this sounds familiar, it is just another retelling of Joseph Campbell’s Hero Myth, celebrated by George Lucas in the plot of the original Star Wars movie.)

It’s through gritted teeth that I tolerate people referring to comic book movies like Iron Man or Superman as Science Fiction, but technically, I suppose, they are.

Other clear examples of Science Mythology are superhero movies based mostly on comic books and graphic novels. It’s through gritted teeth that I tolerate people referring to comic book movies like Iron Man or Superman as Science Fiction, but technically, I suppose, they are. (After all, Superman is an alien crash-landed on earth, and Ironman is a technological superhero. Some, like Thor, are literally Gods.) But, that being said, the underlying philosophy of these stories places them firmly in the outer edges of the Science Mythology category, where the ‘only-one-man-can-save-us’ mentality allows any amount of hero worship with little regard for the historical reality of human misery such worship has generated since the evolution of our species.

‘Batman’, too, could easily be seen as a super-technological God, dispensing justice as he sees fit. (This is only one example of the extraordinarily weird concept of the corporate CEO as superhero that could only be conceived of in comic books, ‘Ironman’ being another.) The Joker is ‘evil’, certainly, and therefore he and his associates can be annihilated without compassion or due process of law. But, when taken from a strict ‘truth, justice and the American way’ point of view, Batman is clearly ‘evil’. There is no compassion shown for how the Joker came to be who he was, and yet the entire story is set up to make us feel sympathy for Bruce Wayne, a rich white boy who lost his parents to ‘evil’, who then also becomes a lawbreaker himself. Based on nothing other than their actions, no reasonable person would have sympathy for either of these people. (Unless, of course, you’re a corporate CEO who daydreams of such things.)

Superman is, by far, the clearest example of what it would mean if religious fundamentalists actually got their way, and their omnipotent God actually ‘returned’ to Earth. (From where exactly, the Bible never quite says.) If you seriously tried to imagine Superman attempting to govern the world using his rather vague principals of ‘good’ and ‘evil’, it would be a nightmare. I mean, the idea of some omnipotent figure, literally an illegal alien, dispensing ‘justice’ with no regard for due process or collateral damage, is exactly the kind of thing that America was allegedly founded to oppose, was it not?

If you seriously tried to imagine Superman attempting to govern the world using his rather vague principals of ‘good’ and ‘evil’, it would be a nightmare.

The most notable elephant (or cash cow) in the Science Fiction room is obviously Star Wars. Star Wars is an odd duck that doesn’t seem to fit comfortably in either philosophy. It has a strong advocation for religious belief, and at the same time seems to have a certain fetish for the secular worlds that it lavishes with such intricate technological detail. But despite the occasional bow to real secular principles, I think Star Wars falls very clearly onto the side of Science Mythology. It seems the light-sabre is a perfect symbol for Star Wars, an antiquated, virtually useless weapon that has inexplicably been upgraded to the technological extreme, but still holding almost magical powers, channelled through the religious practitioner (the Jedi Knight) who handles it. The Speculative Fiction element in Star Wars is hard to ignore, and yet the introduction of religious fundamentalism has brought together two disparate groups that would never otherwise coexist. This mix of the inherent optimism of Speculative Fiction and the religious devotion of Science Mythology has led to unheard-of levels of popularity world wide.

It is hard to ignore the fact that the rise of religious absolutism in the United States corresponded entirely with the rise of the popularity of Star Wars. With rigid fundamentalism driving the faithful from the churches, it seems as though the majority of people who can’t live without faith in something outside themselves has transferred this religious zealotry to the mythological worlds we see in these films. Many lapsed (or lapsing) Christians in America almost certainly equate the religion of Star Wars with Christianity, with the banished British Empire presumably a stand-in for the ‘evil’ Roman Empire that Christ rebelled against.

Many others, disillusioned by the hatred and violence of their respective religions, whether Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, or many others, have found some hope in these stories, which are mixture of religious and humanist values.

For the few dozen people in the world who have never seen Star Wars, it’s a story about a farm boy who lives in the desert who joins a religious minority that is persecuted by an evil overlord (an Emperor, no less) who uses the persuasive powers of their own religion against them. This religious minority commits acts of terrorism and insurrection against this technologically superior Empire (which of course they see as evil) and, except for the odd victory, basically get the shit kicked out of them on a regular basis. (George Lucas made no bones about his use of this template for Star Wars, though I think he might have worded it differently than I have.)

Here’s a very similar story: A disillusioned young man living in the desert encounters a group of rebels who tell him about an ‘Evil’ Empire who persecutes his religion. When asked to join their rebellion, he is torn between his religious beliefs and loyalty to his family who are allies to the Empire. A rebellious sage assumes the father figure for the isolated young man, indoctrinating him further into the fundamentalism of his religion.

After the Empire supports a sworn enemy, they plot a plan of revenge against the Empire. Organizing an alliance of anti-establishment rebels, they attack a major establishment bulwark that shores up the Empire. They destroy the structure and are celebrated as heros by the followers of their religion.

This last one isn’t a movie, of course, but more or less a summary of the events that led up to the attack on New York and Washington in September, 2001. When seen from this perspective, the entire series of Star Wars films is a triumph of religious dogma over technology and modern civilization. My point here is that this illustrates the fact that the ‘Jedi’ religion could be just as easily seen by a Muslim teenager in Gaza as a metaphor for the struggle of Islam against the ‘oppressive’ Jewish State, whose existence would evaporate were it not for the support of the American Empire, to them a technological force of mythical proportions. But it would never occur to the people in America who watch Star Wars that the United States is the evil Empire and that Islam might be the true ‘force’ in the Universe. That the Judean/Christian ‘Empire’ of the United States and Israel are part of the ‘dark side’ trying to eradicate their faith, forcing them to defend themselves. For the Emperor in Star Wars, the death of Luke Skywalker’s guardians at the beginning of ‘A New Hope’ would cause him no more concern in the overall scheme of things than the death of any one of the thousands of civilian families due to ‘collateral damage’ from American drone strikes in Iraq. And yet the rise of the ‘Rebels’ and the rise of the Islamic State are both the result. In that context, to become an Islamic State fighter bent on killing Israeli’s and Americans seems like the morally righteous thing to do, just like Luke Skywalker when he joined the ‘Rebels’.

But it would never occur to the people in America who watch Star Wars that the United States is the evil Empire and that Islam might be the true ‘force’ in the Universe.

(Please don’t get me wrong, here. Israel is, by a very long distance, the most civilized democratic state in that entire region, and in that respect has far surpassed the exceedingly low bar set by the countries that surround it. But democracies are gauged by how they treat their minorities, and sadly, the people of Israel seem to no longer have the moral high ground they deservedly held after the Holocaust. Even if you eliminate the unjustified violence of a small minority of Muslims in Palestine, as it stands today, it would be hard to imagine a Palestinian Prime Minister of Israel, or for that matter a Muslim President of the United States.)

So this begs the question, why are the ‘heros’ of Star Wars acceptable but Osama Bin Laden and his group terrorists? If those who love Star Wars think their little story of a farm boy turned war hero isn’t about terrorism then they need to look more closely. If anyone fits the definition of misguided, religiously radicalized youth, then it would have to be Luke Skywalker and Rey, though they do not fit an American’s definition of ‘terrorist’. It seems the definition of terrorist has grown so polarized, to the point where there is little substantive meaning to the word anymore. Any small act of violence on one side could now fit the definition of terrorism, and, on the other, any act of grotesque violence can be justified.

I would hope that ‘evil’, if it exists, could not be seen as a relative term. By this definition, were George Washington and Paul Revere not terrorists? Or, turning that around, could the terrorists in the Middle East not look to the American Revolution as an example of what they could achieve? Certainly, Osama Bin Laden was a horrifying murderer, but he was still a human being, and to call him ‘evil’ presupposes supernatural intervention, denying his actions are within the purview of any human being, given the right circumstance. American and British forces killed hundreds of thousands of Iraqi civilians in what could only be described as revenge for the deaths of just a few thousand Americans, something that would be considered a horrifying war crime if it had been perpetrated by any other country. Just from the body count alone, would this not be described as ‘evil’? The ambiguity in the definition of this word needs to be eradicated if there is any hope of peace in the real world, or perhaps the use of the word itself should be eliminated.

Maybe I can offer a contrasting story that I see as clearly within the Speculative Fiction realm. In a classic episode of Star Trek, ‘Devil in the Dark’ (wr. Gene L. Coon/ dir. Joseph Pevney) a mining colony is being attacked by a faceless ‘monster’ that eats bare rock and kills everyone it encounters. By the end of the episode, the real monsters turn out to be the Federation and, by extension, the crew of the Enterprise, while the alien was just a mother protecting her children. This story is the kind of good Speculative Fiction that could never be told as Science Mythology. It makes it clear that there is a fine line between what constitutes a good guy and a bad guy, and neither assumption should ever be taken on faith alone.

Captain Kirk might be regarded as a hero, but he is never seen as infallible nor is he seen as superhuman. His ‘superpowers’ are being smart and resourceful and brave. There is no religion propping him up, only his friends and co-workers.(5) Spock, his second in command, rejected the religion of his forefathers to pursue a life of exploration and science. Most of the crew on the ‘USS Enterprise’ are diverse and inclusive, and few subscribe to any overt form of religion. They depend on each other, not on God. There is never a moment in Star Trek where the characters are seen as anything other than flawed human beings. It might be instructive to know how many actual wars were depicted in the first Star Trek television series. (The short answer, none.) This is because the creator of Star Trek, Gene Roddenberry, had seen war first hand and knew that it was something to be avoided if at all possible. The Federation was an organization of peace keepers, reflective of the United Nations as it was after World War 2, where (in theory, at least) colonial interference in other cultures was severely restricted. On more than one occasion, Kirk and the crew ended up being emissaries of peace, rather than rushing into situations, guns blazing. In Star Trek, there is no ‘evil’, no ‘dark side’, unless you consider the support of unquestioned authority as the dark side of humanity. (Or in this case, the Klingons.) The misguided actions of any of the characters were attributed to the characters themselves, not some ‘evil’ force that somehow controls the actions of man.

It might be instructive to know how many actual wars were depicted in the first Star Trek television series. (The short answer, none.)

To be fair to George Lucas, he did try to drag the Star Wars series back toward Speculative Fiction and a more secular view of the universe. In the three prequels (’The Phantom Menace’, ‘The Attack of the Clones’, and the ‘Revenge of the Sith’), he tried to illustrate what the alternative form of government to the ‘evil’ Empire would look like, but it became a cinematic mess, an endless parade of long political speeches and ill-conceived back-stabbing intrigue that was very reminiscent of the gridlocked government of the United States itself.

(If only these films had the political intrigue of House of Cards, then he would have had something.) Worst than over-long and confusing, the movies were derided as boring and uninteresting, even comically naive and racist. But I’m eternally grateful for the effort he expended making the ‘Prequel’ movies, for no other reason than to illustrate the boring hard work representational democracy requires, not to mention the complicated notion of compromise when it comes to governing large groups of people. His failed effort showed the danger of trying to insert the subtlety of reality into a comic-book universe.

Their lack of popularity also showed how blatantly uninterested people are in the real process of governance. If George Lucas had been a better story teller (sorry Mr. Lucas, sir), he could have entertained his audience while showing them where this kind of political polarization could possibly take their country, allowing them to have more patience for the message he was trying to convey. But stretching that message over three long films came across as browbeating the audience, and many religiously devoted fans still resent even the attempt.

“So this is how liberty dies . . . with thunderous applause.”

–Senator Padmé Amidala (Natalie Portman)

I could hardly blame George Lucas for selling out to Disney, though I would not have thought the guy needed the money. (I wonder if his own idealism has been corroded by the ‘dark side’ of capitalism.) I kind of see it as ironic that the Empire in Star Wars was created when the trappings of a religion were used to usurp the will of the people, generating unrestrained political power and infinite wealth. And yet Star Wars (and Marvel) itself, using the religious devotion of the fan base, is now being used by anonymous unrestrained entities to gain near infinite wealth and power in their own realm.

What does going to the ‘dark side’ even mean, anyway? Does it mean you are an innocent, seduced by the outside forces of evil? (ie: The devil made me do it.) If this is the case, does this not absolve the individual of any responsibility for their actions? If you are an oppressed minority with no power, is it okay to use the ‘dark side’ of the force to get a little bit of power, just temporarily, honestly believing that once you have some power, you will use it for good? But how much is enough power? And how do you define good? And how do you react when someone equals your conviction, but defines good in a different way? The ‘dark side of the force’ corrupted Anakin Skywalker, but in the end, he repented and was forgiven. Does this mean he was no longer responsible for his crimes of genocide? (He killed an entire planet full of people, after all.). He was seduced by the ‘dark side’, and attained ultimate power as a result. Saul of Tarsus spent decades persecuting Christians and, after repenting, founded the Christian church as we know it. (Before you get bent out of shape, you have to admit that Peter can’t even touch the influence of Paul in the Christian churches.) He was absolved of his sins by claiming he was possessed by ‘evil’ until his ‘conversion’, whatever that means. Should he have been? If Jimmy Swaggert can be forgiven for his sins, why can’t Osama Bin Laden, after all, both were innocents swayed by the devil, weren’t they?

The religious zeal of Science Mythology allows the execution of any number of ‘Stormtroopers’ with little regard for what lives under the mask. In ‘The Force Awakens’ (wr. Laurence Kasdan, MichaelArndt/dir. J.J.Abrams), we learned that these anonymous soldiers, so casually killed by Rebels in the first six movies, were just like us, human creatures with moral standards and the capacity for self-determination. (I always thought they were some sort of mindless cyborg. Who knew?)

In the ‘Matrix’, bystanders are ‘possessed’ by Agents, who are inevitably dispatched by the ‘heros’ with little regard for the life of the person these Agents possessed, who I presume had lives, families, ambitions and a world view that may or may not have been copacetic with Neo and his cronies. Would the friends and relatives of these people who lost their loved ones to Neo and Morpheus and their band of gun-toting nihilists not see them as ‘evil’?

But, in this world, there is never any doubt that the ‘religion’ of Neo-worship is superior, and like many religious zealots, Neo has little regard for the billions of people plugged into the Matrix who, if they survived its destruction, would be forced into a subsistence living on a planet where their forefathers had ‘scorched the sky’.

Which life would you choose? Personally, on this one, I’m with Cypher, the character who chose to be plugged back in. Hitler famously said that “. . . by the skillful and sustained use of propaganda, one can make a people see even heaven as hell or an extremely wretched life as paradise.” If we really do live in the Matrix, I would like to know about it, certainly, but I doubt I would be willing to immediately call for its destruction.

It’s too bad this Science Mythology religion doesn’t seem to be going away any time soon, and it’s unlikely the converted are going to become aware of how empty this type of fanaticism really is. They will be fed the same reprocessed crap and dutifully parade their way into theatres to see the next installment of ‘Star Wars’ or the ‘Avengers’ and walk away momentarily distracted, but ultimately unsatisfied. In these stories human cooperation and ingenuity are trumped by individual heroics and impossible “powers” that no one could ever possess. And the real work of maintaining a democracy falls to the wayside as we wait for a non-existent “superhero” to save us.

Rich corporate CEO’s are not ‘superheros’, no matter how many tax breaks they receive, in fact I would suggest that maybe they are the ones causing the erosion of our values in the first place. Whatever their economic justification might be, the rights of the stockholders do not trump the rights of citizens.

The entire problem with Science Mythology, in the guise of Superhero movies and the ‘One’ as our savior, is that it inevitably leads to fascists like Hitler, Mussolini, and a thousand other tin-pot dictators who proclaim themselves the ‘messiah’ and say, without embarrassment, “Trust me, only I can fix this, but only if you give me absolute power to do so.” The distinction between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ is never as easy to define as it is in mythology, and you can be assured that unscrupulous people will use than ambiguity to usurp power. Unquestioning faith in any religion needs to be questioned, and, for me, the unnatural popularity of Science Mythology (and also Fantasy Fiction like ‘Game of Thrones’) smacks too much of unquestioning religious devotion, where virtually anything offered is blandly accepted without question.

Speculative Fiction refuses to simply bow down to a Judeo-Christian God, or any other, but challenges him/her at every turn. History has proven that the abandonment of our diversity of belief in favour of religious certainty is only likely to produce less freedom, not more.

***

(1) To this day, I’m eternally grateful to my teacher, Mrs. MacDonald, for her patience and generosity, since I’m fairly certain the story was genuinely awful. Though, at the time, I thought it unfair that I only got a ‘D’.

(2) The 1953 version of ‘War of the Worlds’ (wr. Barré Lyndon/dir. George Pal) had religion imposed on it by the filmmakers. H.G. Wells was decidedly an atheist, illustrated by the fact that, in the novel, when the priest’s fanaticism threatens the life of his unnamed hero, Wells had him beat the priest to death with a shovel.

(3) The 2002 version of ‘Solaris’ (wr./dir. Steven Soderbergh) was a really good movie, but it didn’t really say anything more than the original did, nor did it include anything that had been eliminated from the book. The 1972 film, (wr. Fridrikh Gorenshteyn/dir. Andrei Tarkovsky, from a brilliant book by Stanislaw Lem) was filmed in Soviet Era Russia, Ukraine and urban Japan, lending it a flavour of exoticism that the remake could never hope to achieve. Sorry, Mr. Soderbergh.

(4) I put that one in just to see if you were paying attention. I’m betting not many remember the alien spaceship in ‘Life of Brian’ (wr. Chapman, Cleese, Palin, Idle, Gilliam, and Jones/dir. Terry Jones), but it is there, trust me. One of the best throw-away lines in the film is in the aftermath of the UFO crash: “Oooh, you lucky bastard!”

(5) Well, that is until J.J. Abrams got his hands on the characters. In this series, Kirk is anointed Captain of the Enterprise by the Captain Pike and Spock ‘Prime’ (an angel from the future?) without ever having accomplished anything significant. He is handed exceptional power based solely on his parentage, even after an attempt at mutiny. (The Divine Right of Kings?) This was hardly the only issue I had with this trilogy. For instance, Abrams also had the character of Uhura, an early African American heroic icon, get her position on the Enterprise because she was sleeping with the First Officer. (No, really. She was originally assigned to another ship.) But this is stuff for a future essay.

2,898 total views, 2 views today