Can Machines be Taught to be Moral?

An Essay, August 12, 2018

The Mercedes-Benz ‘Luxury in Motion’ F 015 fully autonomous concept car.

***

“A no-win situation is a possibility that every Commander may face. Has that never occurred to you?”

— Admiral James T. Kirk (William Shatner), The Wrath of Kahn

***

In Mexico it is received wisdom that, as a foreigner, if you are a passenger in a taxi involved in a traffic accident, you should leave immediately. If not, you will be charged along with the driver, regardless of your tangential involvement in the cause of the accident. This is mostly because the driver is unlikely to have insurance and you, as a tourist, likely would. Now, I’m not suggesting that Mexicans are living in some kind of uncivilized anarchy.(1) It’s just a matter of practicality. They know your insurance company is more likely to pay out than get involved in a protracted legal case in a foreign country.

It would seem that we are in a similar situation now with self-driving cars. The way things stand, the criminal liability for any accident still lies solely with the occupant of the vehicle, regardless if they were actually driving at the time of the accident. But, given the primitive state of autonomous vehicles right now, is there no reason to think that anyone else should ever be charged in such an accident?

In March of this year, a woman was killed by one of Uber’s self-driving SUVs in Tempe, Arizona. Though the car was under the control of the computer, the driver, Rafael Vasquez, was found at fault and could face charges of manslaughter. Given that he was watching television at the time of the accident, I certainly agree with that assessment.

However, the software engineers at Uber and the regulators that allowed the car on the street in the first place were absolved of any criminal responsibilities. This doesn’t bode well for the people who will inevitably be injured or killed by these unaccountable electronic entities let loose on our neighbourhoods. If fully autonomous vehicles are ever actually allowed on our streets, it’s not hard to imagine what a nightmare the legal liability would be for any kind of accident, from an insignificant fender-bender, to the allegedly intelligent machine making the deliberate choice to kill someone.

Now that last idea might seem a bit absurd, but there are any number of situations where driverless cars, even when functioning as they were designed, can make a ‘conscious’ decision to commit such manslaughter. That situation has been illustrated in what researchers have called the ‘trolley problem’. The trolley problem has been described in various forms for more than a hundred years, but was popularized by Philosophy Professor Philippa Foot who introduced it into the modern lexicon as a way of studying human dilemmas like the no-win situation.

The best illustration of the no-win scenario is the famous Kobayashi Maru Test in the movie Star Trek 2, the Wrath of Kahn (wr. Harve Bennett and Nicholas Meyer/ dir. Nicholas Meyer). The storyline of the Wrath of Kahn is one extended examination of the trolley problem, where two of the main characters are faced with a no-win scenario and deal with it in different ways. Admiral James T. Kirk (played by William Shatner in his best performance of that character) must face the no-win situation of growing old and dying when his cleverness and denial no longer work against his inevitable decline into old age. At the same time, Commander Spock (played perfectly with ‘emotionless’ pathos by Leonard Nimoy) is faced with a different version of the trolley problem, where he uses logic and reason to justify sacrificing himself in order to save his crewmates and the ship.

“Were I to invoke logic, logic clearly dictates that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.”

— Commander Spock (Leonard Nimoy), The Wrath of Kahn

It could be said most of the stories in the Original Series of Star Trek were various re-imaginings of classical morality plays. There was hardly a moment in the Original Series where morality and doing the ‘right thing’ was not promoted. Many of the episodes even dealt directly with ‘trolley-problem’ type conundrums. (2) These stories offered some indication of the complexity of the problem of trying to impose human morality on a foreign intelligences, whether they be aliens or computers. But the contrived stories were deliberately set up to allow for a morally correct solution to the problem faced by the crew of the Starship Enterprise each week.

“I never took the Kobayashi Maru test until now. What do you think of my solution?”

— Mr. Spock (Leonard Nimoy), The Wrath of Kahn

There are three basic scenarios for the Trolley Problem:

The first is that you are operating a runaway trolley and you are approaching a switch in the tracks. You will almost certainly die in the derailment. There are various combinations of people trapped on either track and you, as the doomed operator, must decide between the two outcomes depending on which track you divert the trolley.

The moral dilemma is what you would do in different situations depending on the perceived value of the victims on either track. For instance, a child on one track, an adult on the other. Five people on one track, and only one on the other.

The second scenario is basically the same situation except that now you are a signalman operating the doomed trolley from a railway switch. Though your own safety is now assured, you know someone on either track will die, but you don’t know who. You are still left with two outcomes, but now there is a another moral decision to make: whether to act or not to act. Not only do you have to decide who dies, you also have to decide if you want to be the one to choose who lives or dies.

The third version of the trolley problem is that you are a bystander with no stake in the incident at all. The runaway trolley is on the main line with lots of people trapped on the track. Near you is a siding with only a few trapped on it. You know the trolley will kill the maximum number of people if you decide not to act. But if you do act, you are making the conscious decision (and accepting the responsibility) of killing the person or people on the other track.

“Most people seem to believe that not only is it permissible to turn the train (trolley) down the spur, it is actually required — morally obligatory.”

― David Edmonds

Now it might seem, at least on the surface, that these three decisions are all pretty much the same, but they are far from it. This first two scenarios describe scenes where a decision must be made by an individual with a stake in the situation. There is an imperative for action, whether you are the trolley conductor or the signalman. Whatever decision they make would be based on their judgement and therefore not seen as being criminally irresponsible.

But this is where the concept of applying morality to these situations breaks down. Being forced into making a decision means morality never enters into the equation. Morality implies intent. If your motives for pulling the lever to save any particular group of people are good, then, in the first two scenarios, any decision you make can be seen as morally serviceable. The only immoral choice would be to abdicate your responsibility and not participate, allowing the events to unfold as if you were not there.

“I don’t believe in the no-win scenario.”

— Adm. James T. Kirk (William Shatner), The Wrath of Kahn

Now the third scenario might seem to call for the same intellectual decision, that one person is sacrificed to save five. But there is a huge difference between the first two situations and the third and this distinction is far more important because it’s, by far, a more common scenario in the real world. A crisis can be averted (killing five people) but only by interceding and reducing the damage (killing only one).

In this situation, you are not forced by circumstance to intercede. As an outside party, you make the decision whether or not to intervene and this is where the real moral conundrum comes into play.

The moral difference can be summed up in one word – agency. Agency is the distinction between action and inaction. Choosing to interject yourself into the events is a genuine moral dilemma. In the Wrath of Kahn, Mr. Spock made the moral decision to sacrifice his life, but he would have died in any case. As in the first scenario, he had a direct stake in the events as they unfolded. Other than morality, what difference would it have made if he chose not to act?

Kirk’s insistence that he doesn’t ‘believe’ in the no-win scenario showed him to be much more morally ambiguous. He could be seen as abdicating his responsibilities in that he had always managed to avoid facing the situation in the first place, and it cost Spock his life.

“I changed the conditions of the test. Got a commendation for original thinking — I don’t like to lose.”

— Admiral James T. Kirk (William Shatner), The Wrath of Kahn

Most versions of the trolley problem are presented as moral conundrums, where human morality is studied based on people’s reaction to each hypothetical situation; what would be the best moral choice in each situation. Seems pretty simple. And most people would agree that it is basically moral to choose the intellectually reasoned decisions with the highest benefit globally. If you are forced to choose between killing five people or killing one, then the intellectual decision would be to kill that one person. But this makes the decision mathematical, not moral.

The idea that five people are, by default, more valuable than one is a fallacy. The one person you kill might be the savior of the world, while the other five are useless drug addicts who rob and steal for drug money. If an adult is trapped on one railway track and a child is trapped on the other, then the choice seems less morally ambiguous. Unless, of course, that child is Hitler. Which would be the better moral choice then? The straightforward math of sacrificing one to save five is so reductive it fails to have any meaning.

The other problem with the trolley problem is that it supposes certainty. Certainty is anything but real outside this contrived situation. In the seconds before the decision is made to intercede, how could anyone ever be certain that you were doing the morally ‘right’ thing? You only have your own perception of the situation to go by. You can morally justify killing one person rather than five only if you are certain the five would have died. Maybe the five could have warned each other, after all five people would have a better chance of seeing the trolley car coming and they would be able to get out of the way. Maybe you could have derailed the trolley and saved everybody. Maybe the five would have only been injured. How could you possibly know this beforehand? The morality of the decision can only have meaning if all the consequences of your actions can be known and evaluated. Otherwise, any altruistic intent could be questioned.

But the biggest problem with the trolley problem is when it involves personal agency. When the agency of an outsider suddenly places another person in jeopardy who would have otherwise survived the incident, that outsider is choosing to impose his morality onto someone else. In other words, that person’s death or injury is a direct result of someone reacting to their moral interpretation of a situation and interjecting their moral will onto it. I could only imagine that this would be objectionable to the family and friends of the victim. What right does that outsider have to impose their a moral choice on them, costing the life of one of their loved ones? It’s impossible to argue the fact that the outsider has committed voluntary manslaughter, regardless of the intellectual reasoning behind it.

Everyone involved in the research surrounding the trolley problem agree there is actually no answer to the problem that would satisfy everyone, and there probably never will be. Most can’t even agree on how many versions of the problem would constitute a definitive list.

“You ask a philosopher a question and after he or she has talked for a bit, you don’t understand your question any more.”

― Philosophy Professor Philippa Foot

So why has solving the trolley problem suddenly become so urgent? Well, the short answer is that, with the advancements in autonomous computer systems, it has become a matter of life and death for thousands, if not millions of people. And one of the primary reasons for the sudden push for autonomous computer systems is the application of these systems for autonomous weapons. The logic goes that if a system can decide who lives or dies on the highway, it can decide who lives or dies on the battlefield. The reason so much funding is being placed in the field is that has direct military applications, from autonomous aerial drones to land-based hunter-killer robots.

Civilian justification for the technology doesn’t remotely trump the military interest and this shows in where the bulk of the research money is coming from. Certainly, there are hundreds of practical military applications for this technology in the defensive sphere. But when it comes to offensive weaponry, where the technology is used to arbitrarily take life rather than protect it, it gets frightening. Regardless of the level of machine learning achieved in any AI system, it’s still a machine, and having machines make the decision to take human life is just not morally correct on any level. There isn’t a single human law that can be devised that applies to the situation where such machines kill the wrong person. For a human to be executed for war crimes is of consequence and cannot be taken lightly. But for a machine, any notion of a deterrent would be completely meaningless. For one thing, if a machine is deactivated for war crimes, it can simply be turned back on at any point.

Clearly, there is no real-world situation that is so simple that it can be compared to the trolley problem. It’s an idea with no foundation in reality. Humans make moral and ethical judgements from a very early age and we make our choices, even our automatic choices, as a result of animal instincts that have been in place for the entirety of human existence. The assumption is that if machines can somehow emulate this process in a meaningful way, then we could have them make these difficult decisions for us. And therein lies the danger of artificial intelligence and autonomous machines of any sort. It’s one thing for me to drive my car off a cliff to save a puppy on the road. But, if a driverless car is going to drive me and my family over a cliff in order to save someone else, then I damn well want to know how the algorithm works before I ever set foot in that car.

As sophisticated as these algorithms can get, they will never actually understand human morality and values because we don’t understand them ourselves. So how can we expect to reproduce it using a few thousand lines of computer code? These life-and-death decisions require a value judgement, and there is no judgement of value or morality in any decision a computer algorithm makes. They simply do not have the means to learn such morality any more than a psychopath could. And are we really proposing that all our most difficult decisions be handed over to mechanical psychopaths?

“If the Martians take the writings of moral philosophers as a guide to what goes on on this planet, they will get a shock when they arrive.”

― Philosophy Professor Philippa Foot

And even if we could teach a computer to make moral judgements, whose morality and value systems should such an algorithm based? But just because some computer geek sitting at a basement work station at Uber headquarters thinks something is moral, doesn’t mean I agree. And I’m fairly certain my morality is different from yours. Certainly our moral judgement is different than a Muslim hijacker’s morality, or a Christian Fundamentalist waiting for the rapture. But it takes an enormous amount of arrogance to automatically assume a machine’s morality is, by default, superior.

Another danger is that AI can make such a decision in a millisecond. As a human being, I would never be given the luxury of making such an intellectual decision in that time frame. These types of no-win situations are rare occurrences, and having time to ponder the morality of such a decision just before it occurs is unbelievably contrived. I would instinctively react to the situation without thought, or be paralyzed and not react at all. Either way, the situation would always be seen as an accident, something beyond my control and therefore beyond my capacity of blame. But the AI system in the car can make this perfectly logical, intellectually-reasoned decision in a millisecond, making the killing of an innocent person a deliberate act that cannot be defined as accidental.

“They say it got smart. . . It decided our fate in a microsecond.”

– Kyle Reese (Michael Beihn), The Terminator

The current solution for corporations to skirt their responsibilities , of course, is a manual override. This will give the driver of the car the option of over-riding the car’s decision, if such a thing were even possible within the time frame. Problem solved as far as the manufacturer is concerned, since this is a way of shifting liability to the occupant of the vehicle if s/he doesn’t switch the system off in time. If the human is considered the moral arbiter of the car’s decisions, then this absolves the manufacturer and the programmer of liability, both legally and morally. This is what happened in Tempe Arizona. (3)

“When morality comes up against profit, it is seldom that profit loses.”

― Shirley Chisholm

The majority of these tech companies have solved the liability problems of driverless cars by making every effort to divert the ethical responsibility for their under-developed — and sometimes outright faulty — products onto anyone who is too dumb to know what they are trying to do. It’s the reason why there is a huge push toward ‘no-fault’ insurance. What this does is make the general public liable, while the people who perpetrated the crime not only go free, but make huge profits. But the very idea of no-fault insurance is completely contrary to the so-called American ideal of personal responsibility. If the battle for universal health care is any indication, then its doubtful anything like no-fault insurance will even be accepted.

But you still have another problem in that there is one, and only one, guiding principal in the commercial application of these systems: Capitalism. Let’s imagine a idealized world where some unknown genius was able to get past all these barriers and produce a morally upstanding autonomous system that would make all the right decisions in all circumstances. They will patent that system, preventing anyone else from using it. Competition will dictate that others will also develop systems, and their price will have to come down to compete. Anyone who develops a competing system will be forced to cut corners, and all the hazards that entails. The free market has always dictated that an adequate product at the lowest price always wins out. (4) What could possibly go wrong? Cut rate Levi’s are one thing. Cut rate AI is outright dangerous, especially when it comes to a driverless car, or a hunter-killer robot.

“Once you give a charlatan power over you, you almost never get it back.”

― Carl Sagan

The most obvious culprit implicated in the questionable decisions of an autonomous vehicle are the programmers themselves. If the car’s program made a decision that cost someone their life, how could it not be the fault of the programmer who created the artificial intelligence code in the software? But the manufacturer and the programmer are equally likely to point the finger at the AI system itself, despite the fact that they are the ones responsible for manufacturing it, programming it, and giving it the capacity of independent decision making.

They would claim, with some justification, that placing fault with the programmers doesn’t apply because AI doesn’t work that way. It does not come down to a culpable person consciously imparting weighted numbers into a set of rules. The algorithms used in AI are allegedly self correcting, allowing the computer to modify its own behavior in response to previous decisions. Mistakes are inevitable, even for humans. These machines learn from their mistakes. Learning from those mistakes requires a shift in behavior that would, in theory, prevent the mistake from happening again.

But what exactly does it mean when it is claimed that the algorithm ‘learns’ from its mistakes? The implication seems to be that it learns from its mistakes ‘just like humans’. But that’s just not really the case. The mistake, by definition, was a result of an unforeseen circumstance, something the machine has never encountered before and was unable to predict. But humans are capable of imagining scenarios that they have never encountered before, and can adjust their behavior accordingly. Machines cannot do this.

“I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that.”

— HAL (Douglas Rain), 2001: A Space Odyssey

A human learns from an early age that if you fall out of bed, you hit the floor and hurt yourself. A human can interpolate this to reason that if you step off a cliff, it will hurt even more. Humans can see how one situation is analogous to another without being explicitly told. But an autonomous vehicle would have to drive off the cliff to learn this lesson. In humans, these intricate systems of association and interpolation are complex and inscrutable; so far beyond our intellectual understanding that they’re impossible to reproduce even theoretically. The developers of these autonomous systems seem to think that this ability will somehow appear out of the complexity of their systems. But it’s not the accumulation of information that matters here. It’s how that information is being used.

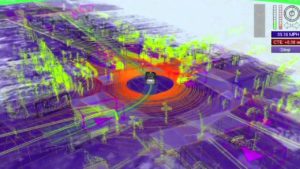

It’s presumed the autonomous car not only has the time to make a decision, somehow has all the information it needs too. But how could it possibly have this information? Chaos theory proved that complex systems cannot be predicted without knowing every variable down to infinite resolution. Current autonomous systems are not even remotely close to this. The LIDAR and Photogrammetry scan. (5) are comically inaccurate when compared to human sight and sound. There is no where near enough information in these systems to make any kind of nuanced decisions that could cost someone their lives.

And then there is the questionable predictive capability of the algorithm itself. Making short-term predictions under strictly controlled conditions is difficult enough. But making life-and-death predictions under real-world conditions is orders of magnitude above anything we can do today with computers. A computer can be taught to catch a baseball (a spinning spherical ball) because its behavior is classically Newtonian and relatively easy to predict. But a tumbling football, an oblong object on an elliptical path, has so much chaos built into its shape and its environment as it moves that a robotic wide receiver could never be programmed to catch it with even close to the same consistency as a human being, never mind with the skill of a professional wide receiver. Human beings rarely follow a fixed trajectory, so how could it possibly predict the behavior of a pedestrian crossing the street with any degree of accuracy? Would this logic not make the pedestrian liable for her own death because she didn’t follow a predictable path across the street?

“All men make mistakes, but a good man yields when he knows his course is wrong, and repairs the evil. The only crime is pride.”

― Sophocles, Antigone

Human beings make mistakes, and most catastrophic accidents are usually caused by a series of simple mistakes, any one of which was not terribly significant on its own. There is little consequence if Netflix chooses the wrong movie to recommend to you (as it does for me seemingly at every turn). But autonomous systems have much higher stakes when they make a mistake. The Uber car in Arizona made a mistake; it apparently identified the pedestrian first as an obstruction, then a pedestrian, then a vehicle, and then a pedestrian again, all in a split second. The programmers made a mistake by not allowing the automatic braking system to function while there was an operator in the car. The driver made a mistake by glancing down at his television screen at exactly the wrong moment. The regulators made a mistake by allowing a system they didn’t understand function in a public space that endangered real people. But the AI, the company, the programmer and the regulator were found not to be at fault, only the driver, despite the fact that he wasn’t actually ‘driving’ the car that the time. If an autonomous system can’t predict the consequences of just these few mistakes, what are the odds that we can foresee the consequences of thousands of unpredictable factors needed to make a moral decision?

There has always been a consistent legal precedent for car manufacturers that clearly states that they are liable for any defective system they put in their vehicles, whether an unreliable light switch or the recent problem with airbags. And autonomous systems have already been integrated into modern vehicles safely, many becoming indispensable safety features like electronic fuel injection, anti-lock brakes, airbags, side collision warnings and collision avoidance. But they are defensive measures for the most part, and few involve agency.

If laws are passed shielding these corporations from prosecution and liability, then this responsibility would be removed, leaving victims with no other means of restitution. If we allow this to happen, what recourse would victims have for wrongful death of a human being brought on by such a machine? Where would the blame then lie?

I firmly believe that, ultimately, the only moral question that matters concerning autonomous vehicles of any sort lies not with the vehicle, but with us. It’s clear to anyone who examines the idea of driverless cars closely that this is an abdication of responsibility on everyone’s part, from the ‘drivers’ of these autonomous vehicles, to the people who build them, to the regulators who allow them to operate in public. When a person assumes control of a car, there is a tacit agreement that they are responsible for the safe operation of that vehicle. The real immoral act is abdicating that responsibility. Any human being with any sense of morality would know this immediately if they were ever in the position where they helplessly watched their autonomous car plow into a group of pedestrians, whatever the reason the computer might give for the decision. I, personally, would be devastated, as would be virtually anyone with any sense of morality. The car itself would not be capable of caring one way another.

“I am free because I know that I alone am morally responsible for everything I do.”

— Robert Heinlein

But now we have the situation where we have hundreds of pilot projects all over the world that are studying the viability of a system where all moral decision making is taken up by the AI systems in the cars. Inevitably, someone ended up dying, and a very strong legal case is being made against the person sitting in the driver’s seat, regardless if he was actually driving the car or not. So, effectively, it comes down to the culpability of the passenger. And, like in Mexico, the best the passenger can hope for is to get away quickly enough so that they can’t be implicated.

***

(1) – Mexico would be fantastic were it not for the mobs of uncivilized tourists who flock there.

(2) – Most notably, “The Galileo Seven” and “City On the Edge of Forever” dealt with the trolley problem directly. “The Doomsday Machine,” “A Taste of Armageddon,” and “The Ultimate Computer” dealt with the dangers of deferring human decision-making to machines. There are many more indirect references, I’m sure.

(3) – Tesla was also absolved of its responsibility for a fatal accident with this handy legal maneuver.

(4) – This is why we ended up with VHS video instead of the much-superior Betamax, remember?

(5) – LIDAR is a device to scan terrain with a laser. Photogrammetry is the construction of a 3d model of terrain interpolated from still photographic images.)

948 total views, 1 views today