Blind Prejudice and the Naming of Sports Teams

An Essay, March 12, 2019

***

DISCLAIMER:

PLEASE BE ADVISED THE FOLLOWING ESSAY

CONTAINS OFFENSIVE LANGUAGE AND IMAGERY.

***

“A warrior kills only to protect his family, or to keep from becoming a slave. We believe not in death, but in life, and there is no object more valuable than a man’s life.”

— Kintango (Moses Gunn) “Roots”

It’s almost a given that, as a white male over the age of sixty, I’m racist. I’m certainly not proud of this, but I am fully aware of my shortcomings. With my upbringing, I can be a victim of my own prejudices even today, despite every good intention. I have resigned myself to the fact that I will inevitably slip up, and I will have to vigorously apologize whenever I fall into any sort of self-inflicted racial trap I set for myself. Thankfully, these occasions are rare. I suppose every white male of my generation is in that position now and perhaps that’s not a bad thing.

Though I grew up in the height of the civil rights movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s, I had never actually met an African American until well after University. I’m talking about a descendant of a person from Central Africa who had been brought to North America as a slave. I had met many people with dark skin, of course. We had two South Asian teachers and their families in our High School at the time. And one of the store owners in a nearby town was Ethiopian, I believe. (1)

“Chains ain’t right for n—–s, Fiddler!”

— Kunta Kinte (LeVar Burton), “Roots”

Though we did learn about American slavery in school, it wasn’t until I watched the mini-series “Roots” in 1977 that I really understood the history of black slavery in the United States. (2) And it wasn’t until I moved to Halifax, Nova Scotia in the late 1970s that I finally met an actual black American.

Believe it or not, when I moved there after university, I actually went on a quest. I had learned in history class that some of the loyalist blacks who had settled in Halifax after the American Revolution were descendants of slaves. But even then, when I finally tracked one down — a really great guy named Will who took pity on my ignorance – I was hardly surprised to find he was nothing like his television counterparts, my only frame of reference at the time.

Even to this day, none of the African-Americans I’ve met even remotely resembled most of the characters I saw on American television during that period. Don’t get me wrong, there was occasionally a glimpse of recognizable black people on television. Say what you will about “Sanford and Son,” (played by Redd Foxx and Demond Wilson, created by Norman Lear) at least the characters felt like real people with real jobs and genuine flaws and strengths. Sydney Pottier’s performance in “In the Heat of the Night” (wr. Stirling Silliphant/ dir. Norman Jewison) certainly didn’t jibe with the typical portrayal of blacks on American network television. These were heroic figures mostly because they were so normal.

I personally found most representations of blacks on television almost as insufferable as the racism itself. I believe Norman Lear is a television god, but there were a few of his shows, especially the sitcoms, that dealt with black stereotypes in a really uncomfortable way. I’m talking about characters like ‘J.J.’ Evans (played by Jimmy Walker) on “Good Times” (cr. by Mike Evans, Norman Lear and Eric Monte).

Mr. Lear was hardly the only one guilty of this, of course. Later examples of this were Erkel (played by Jaleel White) on “Family Matters” (created by William Bickley, Robert L. Boyett, and Thomas L. Miller, et.al), and Whitley (played by Jasmine Guy) on “A Different World” (created by Bill Cosby). They pranced around in exaggerated characters that were only one step removed from Amos and Andy (played by Alvin Childress and Spencer Williams). I’m certainly not blaming the actors for this. It was a job that few others could claim to hold. But that didn’t make it any easier to watch.

It wasn’t until the 1980s and The Cosby Show (created by Ed Weinberger, Michael Leeson, and Bill Cosby) that white Americans saw what everyone had always suspected: That black people are just like us. People today can’t even imagine the revelation it was to see an African-American man playing a happily married professional whose wife was also a professional and whose family was just, well, normal. (3) But it really begged the question why this show was such a revelation.

“We are not Africans! Those people are not Africans; they don’t know a damned thing about Africa!”

— Bill Cosby

Not long after his show was cancelled, Mr. Cosby tried to make the case for American blacks to stop using the past to justify their bad behavior and he got taken down a notch or two for it. (4) He was a bit frustrated with the constant reference to the past and he just wanted to have a different conversation and I get that. I did see his point even if I don’t necessarily agree with it. African Americans have been lamenting their ancestors treatment ever since they were freed from slavery. And it’s true that most African Americans today are not subjected to the levels of grinding poverty and subjugation they had in the past.

I did see his point even if I don’t necessarily agree with it. African Americans have been lamenting their ancestors treatment ever since they were freed from slavery. And it’s true that most African Americans today are not subjected to the levels of grinding poverty and subjugation they had in the past.

But Mr. Cosby failed to see the need to maintain constant pressure, evidenced by the backsliding just since the recent election a certain racist president. Black Americans have it better now only because of more than 150 years of constant application of what little power they possessed. It has always been this way for minorities. Education and money are meaningless without the power to maintain it. Money and education did not help the Jews in Nazi Germany. It did not help the intellectuals in Soviet Union after the revolution. And it won’t help minorities in the United States unless they are willing to exercise their power. Maybe the descent from slavery isn’t the immediate problem for African Americans, but the systemic racism they have endured since then certainly is.

“Well, I took a trip to (Kenya) — I saw people. African people. I saw people from other countries, too, and they were all kinds of colors, but I didn’t see any ‘n—–s.’ I didn’t see any there because there are no ‘n—–s’ in Africa.”

— Richard Pryor

***

Now, some would have you believe that institutional racism doesn’t exist, but it’s easy to refute this by pointing out where racism is not only up front, but completely acceptable to millions of people, namely with First Nations peoples. When I indicated my own racism earlier, I was not referring to African Americans. After all, it would be difficult (though not impossible) to be prejudice against a group of people I had never encountered. But there decidedly was a great deal of prejudice in the community where I grew up. There was a very specific hierarchy that virtually everyone cleaved to, and it was never questioned for the most part.  At the top were the British (Anglo-Saxon Protestant Anglican), then the Scots (Protestant, but Methodist) and then came the Irish (mix of Protestant and Roman Catholic). Then came our group, and the Acadian (or Breton) French (also Catholic). The one thing we all had in common, however poverty stricken we might have been, was this: At least we weren’t ‘effen Indians’ (also Catholic, but just barely).

At the top were the British (Anglo-Saxon Protestant Anglican), then the Scots (Protestant, but Methodist) and then came the Irish (mix of Protestant and Roman Catholic). Then came our group, and the Acadian (or Breton) French (also Catholic). The one thing we all had in common, however poverty stricken we might have been, was this: At least we weren’t ‘effen Indians’ (also Catholic, but just barely).

Though I was indoctrinated into this way of thinking at a very young age, I could never completely atone for my attitude toward those people who lived on the nearby reservation when I was growing up. It was only my friendship with three intelligent, funny First-Nations classmates in high school that changed my attitude. None of these boys could ever be described as ‘savages’. And, thankfully, none would tolerate my racism. Also, it was a little hard to reconcile calling them ‘Indians’ when my science and geography teachers were actual Indians from India. So I was forced to change my attitude and I am forever glad for it.

And this is why I’ve taken up the unwelcome task of dealing with the clearly visible bigotry in some American professional sports names. Sports are not really my thing, but I felt compelled to say something. I understand that the converted can sometimes be more offended by such things than the victims, but in this case I think I am justified in pointing out the hypocrisy.

It’s only because I had friends who are constantly having to endure such discrimination that I find it so debilitating to see a professional sports club, comprised most of black men, unashamedly wearing a jersey with a racist cartoon ‘Indian’ — or worse, the name “Redskins” — proudly emblazoned across their chest. It’s hard to believe that, in 2019, we’re in a situation where a racist can wear their racism so blatantly on their sleeve, literally. I have yet to find a First Nations person who would admit to being a fan of the Washington Redskins or the Cleveland Indians. That’s hardly surprising. I just find it hard to believe anyone else would.

“But what that Comanche believes — ain’t got no eyes, he can’t enter the spirit-land. Has to wander forever between the winds.”

— Ethan Edwards (John Wayne), “The Searchers”

***

Unfortunately, most North American’s ideas about First Nations people were shaped by Western movies and television. Before revisionist Westerns like “Little Big Man” (wr. Calder Willingham/dir. Arthur Penn) and “Dances With Wolves” (wr. Michael Blake/dir. Kevin Costner) came a long, most Westerns had a common theme — the hatred and fear of the native ‘savages’. The pinnacle of such movies, or at least the one with the most obvious tropes, was “The Searchers” (wr. Frank S. Nugent/ dir. John Ford). At the first viewing of “The Searchers”, I didn’t have a problem when Ethan Edwards (played by John Wayne) shoots the eyes out of a dead Comanche so that the warrior “can’t enter the spirit-land.” But on second viewing, it was bothersome that it wasn’t enough to kill the Comanche; Edwards had to desecrate him, too. To not just end the man’s life in this world, but in the hereafter too. Even the worst depictions of racism today would be reluctant to portray the death of a black man in such a manner. The only movie scene that comes close to such hatred would be the ‘curbing’ incident in “American History X” (wr. David McKenna/dir. Tony Kaye) So what could possibly generate such visceral hatred?

By the time of the ‘wild west’ depicted in these movies, eastern tribes like the Cherokee had been repeatedly forced to migrate into the traditional lands of other rival tribes like the Apache, the Comanche, and the Navajo, inevitably increasing the hostility between tribes and the settlers. How could it not? They were trapped between traditional enemies and murderous colonist invaders. They had no choice but to fight back. This detail is conveniently left out of “The Searchers” and most other Westerns as it would have conflicted with the ‘manifest destiny’ that was the theme of these stories. The director John Ford might have professed to stand up for the Navajo, but he never questioned the white man’s right to conquer the west.

But Ethan Edwards was hardly the only portrayal of this kind of racist character in Westerns. There were literally thousands of movies and television shows where Native Americans were slaughtered with even less thought than this. I highly recommend a wonderful documentary called “Reel Injun” (wr./dir. Neil Diamond, Catherine Bainbridge and Jeremiah Hayes). In it, the directors had some of the Navajo dialogue spoken by the actors on-screen translated into English. (5) What the actors were saying was hardly complimentary or suitable for a child to hear. The film makers were so racist that it never occurred to them to translate what the actors were saying; that it might actually be a real language they were speaking.

“Well, there are some things a man just can’t run away from.”

— John Wayne

***

But the reality was that most of the Indigenous peoples were not particularly belligerent against the White Europeans initially. They were forced into that role by the behavior of the colonists. The natives didn’t turn against the passengers of the Mayflower, the passengers on the Mayflower turned against the natives. They were the very definition of rude guests, and would not have survived their first winter were it not for the generosity of the native tribes who helped them. In thanks, the settlers slaughtered them.

But the reality was that most of the Indigenous peoples were not particularly belligerent against the White Europeans initially. They were forced into that role by the behavior of the colonists. The natives didn’t turn against the passengers of the Mayflower, the passengers on the Mayflower turned against the natives. They were the very definition of rude guests, and would not have survived their first winter were it not for the generosity of the native tribes who helped them. In thanks, the settlers slaughtered them.

Far more indigenous people died in the European invasion of North America than in all of the American slave trade. It could even be said that the genocide that resulted from the European invasion of the Americas is easily an order of magnitude above the death and misery inflicted on African slaves in the United States. When you consider this, the least we can do is afford their survivors the same respect demanded by African Americans.

“And I can see that something else died there in the bloody mud, and was buried in the blizzard. A people’s dream died there. It was a beautiful dream –”

― Black Elk (Black Elk Speaks)

My personal interactions with First Nations people when I was growing up were exclusively the Mi’kmaq, whose traditional lands comprised parts of New England, the Maritime Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula. In the beginning, their relationship with European settlers was mostly amicable, especially with the French traders they first encountered. The English settlers were more confrontational, especially when the French were driven out of the area in the early 19th century. And even then, it wasn’t until the British imposed draconian rules on native tribes just before Canadian Confederation in the middle of the 19th century that they became hostile. But by then it was too late for the Mi’kmac to fight back. They had been converted to Christianity and integrated into the new colonies and, like most conquered peoples, they did what they could to assimilate into the new culture imposed on them.

“There is an endless supply of white men, but there has always been a limited number of human beings.”

— Old Lodge Skins (Chief Dan George), “Little Big Man”

***

Contrary to prejudicial beliefs, no native North American peoples have actually had anything resembling red skin.

The original ‘redskins’ are the tribes of indigenous people called the Beothuk who occupied the Island of Newfoundland for about 500 years before the arrival of Venetian explorer John Cabot (Zuan Chabotto) in 1497.

The Beothuk used red ochre to paint their bodies during their spring rituals, causing the European settlers to call them ‘Red Indians’ or ‘Redskins’. Though this ritual body painting was hardly universal when it came to indigenous North Americans, the name stuck.

From the beginning, the Beothuk refused to interact with the English and French settlers who came after and they were systematically forced to retreat as the invaders slowly swallowed their land. Little is know about them because they were never integrated into the culture like the Mi’kmac tribes that dominated the rest of the Maritime region. They were never converted to Christianity and very few learned English or how to write. Unfortunately, their refusal to integrate led to their eventual extinction. As a result, the Beothuk are no longer around to protest the use of the ‘Redskins’ pejorative.

***

“I’ll never change the name of the Redskins. You have my word on that.

–Daniel Snyder, Washington Redskins football team owner

Daniel Snyder has sworn that he will never change the name of his organization. His attitude is the very definition of blind racism. In his refusal to acknowledge his racism, it’s almost impossible to reason with him when it come to making this long-overdue change.

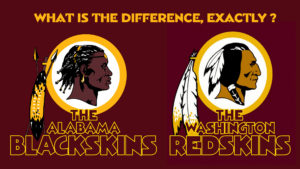

Now, I could spend hours making a convincing case for why these sports logos are racist, but it would be much easier to simply illustrate the problem. A picture is worth a thousand words, after all. I took it upon myself to create the logos for two fictional sports teams: The Alabama ‘Blackskins’ and The San Francisco ‘Laundrymen’. I certainly hope that if any team owner suggest either of these names for a National Football League team, the league would never allow it. I’m also hoping you’re as offended seeing them as I was making them.

The owners of the Chicago Black Hawks hockey team would rationalize that the warrior chief depicted in their logo is a proud depiction of Black Hawk, the famous Warrior Chief of the Sauk tribe of the American Midwest. (6)  It’s meant as an image of reverence, not malice. And I suppose it is, in their minds. But my depiction of the Maasai Warrior in the Blackskins logo is also a proud warrior meant as a respectful tribute. (7)

It’s meant as an image of reverence, not malice. And I suppose it is, in their minds. But my depiction of the Maasai Warrior in the Blackskins logo is also a proud warrior meant as a respectful tribute. (7)

The depiction of Chief Wahoo on the sleeve of the Cleveland Indians jersey can’t make the same claim. Nothing complimentary can be conjured up about this image, witnessed by the ease with which I was able to convert it into the worst kind of racist Asian stereotype. Now, to be fair, the Cleveland Indians have decided to drop the depiction of Chief Wahoo from their official logo this year. But come on, it’s 2019 for Christ’s sake.

***

The only real indigenous tribe of ‘Redskins’ that ever existed were the Beothuk, and they were victims of genocide. But just because the Beothuk are extinct doesn’t make it morally acceptable to use derogatory representations of their culture on a football jersey. At least African Americans have the opportunity to speak up for their rights. The Beothuk can never speak up for themselves. They’re gone forever.

The very fact that these people were exterminated makes using the term ‘Redskin’ easily as offensive as ‘n—–r’. Naming your sports team the ‘Redskins’ is the equivalent of naming them after the Jews of Auschwitz. (I thought about converting the ‘Redskins’ logo to the ‘Auschwitz Jews’, but it was so offensive I couldn’t bring myself to do it.)

Imagine if white Americans, instead of enslavement, had succeeded in exterminating African Americans into near extinction and then had the temerity to name their sports team the ‘Blackskins.’ How do you think that would make the surviving black Americans feel? I would hope that any black player on the Washington ‘Redskins’ would never agree to play football for the ‘Alabama Blackskins,’ so why would they agree to play for the ‘Redskins’ unless they too were racist against Native Americans.

It’s difficult to imagine the mental gymnastics required for a victim of racism to be seen to be openly racist against someone else. And that’s the problem with blind prejudice. By definition, it isn’t apparent to those who participate in it.

So, even after all the controversy, if Daniel Snyder still can’t see the need to change the name of his football team, then I suggest he create a real sports jersey for the Alabama ‘Blackskins’ or the San Francisco ‘Laundrymen’ and wear it around any populated region of the United States. I’m fairly certain there would be no shortage of people who would volunteer to explain his ignorance to him.

***

(1) – I also knew a family from Libya and another from Egypt, all of whom were African, too, even though they didn’t have dark skin.

(2) – Too bad the author, Alex Hailey, plagiarized much of that story of “Roots” from another work, Harold Courlander’s “The African”.

(3) – The success of this show makes Cosby’s demented personal life all the more harsh for its betrayal.

(4) – At the time, Mr. Cosby could say such things and not damage his career too much.

(5) – The film they referenced was “A Distant Trumpet,” (wr. John Twist/dir. Raoul Walsh).

(6) – Who, incidentally, fought for the British against the Americans in the War of 1812. That makes him an awkward choice for an American sports team, even ignoring the racism.

(7) – Okay, so the shield is actually Zulu, but what’s the difference? All black Africans are the same, aren’t they? Just like all Native Americans are just ‘injuns,’ right? But they aren’t, are they. A Mohawk is not a Navajo in the same way a Scot is not an Italian. They come from two completely different thousand-year-old cultures separated by a thousand miles.

1,317 total views, 1 views today