Scrooge: A Christmas Carol (2022)

***

Movie mogul Samuel Goldman reportedly once said, “If ya wanna send a message, use Western Union.” (1) But despite Samuel Goldman’s misgivings, many authors do set out to deliver a message in their work, sometimes to great effect. Certainly, Dickens’s A Christmas Carol is one of those pieces. Dickens intended his novella to cause people to reflect on their obsessive pursuit of money at the expense of their spiritual selves, a message that should resonate particularly well in today’s consumer society. The sentimentality of the story aside, the message of A Christmas Carol has, over the last 175 years, struck a chord like few other classics.

A Christmas Carol has been reinterpreted for the movies almost from the beginning of cinema, running from the 1901 adaptation Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost (wr. Charles Dickens and J.C. Buckstone/dir. Walter Booth), to the 1951 classic Scrooge (wr. Noel Langley/dir. Brian Desmond Hurst), to Bill Murray’s Scrooged (wr. Mitch Glazer and Michael O’Donoghue/dir. Richard Donner), all the way to the recent frantic mess from Apple+ called Spirited (wr. Sean Anders and John Morris/dir. Sean Anders). And who knows how many other animated films, musicals, stage plays and re-novelizations on top of that. Ironically, the Muppet Christmas Carol (wr. Jerry Juhl/dir. Brian Henson) may have offered the most respect to the original work, using actual passages from the printed text in the on-screen narration.

A Christmas Carol has been reinterpreted for the movies almost from the beginning of cinema, running from the 1901 adaptation Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost (wr. Charles Dickens and J.C. Buckstone/dir. Walter Booth), to the 1951 classic Scrooge (wr. Noel Langley/dir. Brian Desmond Hurst), to Bill Murray’s Scrooged (wr. Mitch Glazer and Michael O’Donoghue/dir. Richard Donner), all the way to the recent frantic mess from Apple+ called Spirited (wr. Sean Anders and John Morris/dir. Sean Anders). And who knows how many other animated films, musicals, stage plays and re-novelizations on top of that. Ironically, the Muppet Christmas Carol (wr. Jerry Juhl/dir. Brian Henson) may have offered the most respect to the original work, using actual passages from the printed text in the on-screen narration.

With the recent release of Netflix’s Scrooge: A Christmas Carol (wr./dir Steven Donnelly), a computer animated musical interpretation of the holiday classic, we’ve taken another long step away from the problematic source material. This project is itself an adaptation, not of the original material, but of the 1970 musical Scrooge (wr. Leslie Bricusse/dir. Ronald Neame) starring Albert Finney. This noisy production would be so foreign to Dickens it’s doubtful he would even recognize it as his own work.

***

The problem is that surprisingly few people have actually read the original text, and therefore have little information on how they should interpret the original author’s intent, even if they cared to find out. The character of Scrooge was allegedly based on Dickens’ own father and two well-know miserly characters in London at the time; Parliamentarian John Elwes and banker Jemmy Wood. While these men were unattractive caricatures in the flesh, Dickens himself offered little in the way of a physical description of Ebenezer Scrooge, with only small hints of having ‘old features’ including a ‘a pointed nose’, ‘wiry chin’ and ‘ferret-eyes’. But this is hardly what comes across when surveying the depictions of Scrooge since the beginning of cinematic history.

Sometimes the most obvious racist or anti-Semitic works are right in front of your nose. Or maybe as clear as the nose on Scrooge’s face. Though the character of Scrooge in Scrooge: A Christmas Carol is surprisingly young and sprightly for an allegedly ‘old miser’, the filmmakers couldn’t resist the stereotype of the hooked nose. This is not a clear indication of anti-Semitism, of course. But it is a clear indication of the anti-Semetic interpretations of the story over the decades since it was written. And there-in lies the problem. When there is little investigation into the source material, it’s difficult not to fall into certain anti-Semitic traps when dealing with a property that is so immersed in the Christian culture where these stereotypes originated.

Sometimes the most obvious racist or anti-Semitic works are right in front of your nose. Or maybe as clear as the nose on Scrooge’s face. Though the character of Scrooge in Scrooge: A Christmas Carol is surprisingly young and sprightly for an allegedly ‘old miser’, the filmmakers couldn’t resist the stereotype of the hooked nose. This is not a clear indication of anti-Semitism, of course. But it is a clear indication of the anti-Semetic interpretations of the story over the decades since it was written. And there-in lies the problem. When there is little investigation into the source material, it’s difficult not to fall into certain anti-Semitic traps when dealing with a property that is so immersed in the Christian culture where these stereotypes originated.

As described on the novella, Scrooge is a humourless miser who hunches over his coins like a dog over a bone. A money-grubbing businessman who abuses his Christian employee right up to the end of the work-day on Christmas Eve. He refuses to acknowledge the religious principles of his employee and even resents one day off per year to celebrate. And he certainly does not celebrate the Christian holiday himself.

… it is a clear indication of the anti-Semetic interpretations of the story over the decades since it was written.

The story’s message is also suggestive that this money-grubbing miser could only be shown the error of his ways and achieve true happiness through his conversion to Christianity. When the character of Ebenezer Scrooge is described in isolation like this, it’s hard not to imagine him as anything other than a Jewish caricature.

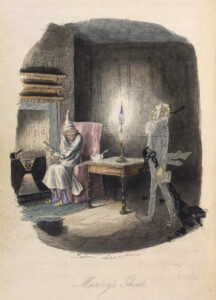

This perception is not helped by the original illustrations by John Leech. When Leech was tasked with portraying Scrooge, his image of what a money-grubbing non-Christian would look like could only be called a Jewish caricature. And in the ensuing adaptations, almost no one saw the need to correct this error, not even Dickens himself. Dickens might be forgiven if this was a single occurrence, but it is quite clear that most of the other ‘money-grubbers’ in his stories are represented as Jews if not in name then in spirit. The likes of Fagin in Oliver Twist (1839), Ralph Nickleby in Nicholas Nickleby (1838-9) and Joshua Smallweed in Bleak House (1852-3) and many others, were all illustrated as this anti-Semitic caricature.

When taken as read, the novella of A Christmas Carol is definitely a story of its times. Most of the population of an overtly Christian country like England would have hardly objected to such depictions. Christmas at the time Dickens wrote the story is not what we think of it today. It was, by and large, a religious celebration, and a distinctly Christian one. They would certainly look on someone who didn’t celebrate Christmas with suspicion, regardless of whether or not they actually were Jews. I’m not suggesting the novella is an anti-Semitic diatribe, or even religious propaganda, but it does deliver a heavy-handed Christian message.

Christmas at the time Dickens wrote the story is not what we think of it today. It was, by and large, a religious celebration, and a distinctly Christian one.

Dickens often suffers from the same fate as many authors whose work has fallen into the public domain; the Americanization (ie: the Disney-facation) of their works (or worse). Authors like William Shakespeare, Mary Shelley, H.G. Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle, Oscar Wilde and many more have all seen their work reinterpreted for the American audience, stripping the meaning and the message from the stories to suit whatever agenda the filmmakers imagine audiences want to see.

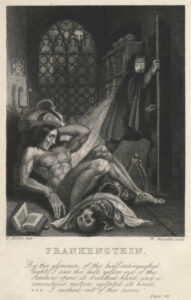

The original victim of such careless adaptations is, of course, Mary Shelley and her depiction of Frankenstein’s monster. Almost everyone who reads the book is surprised to learn that the monster is of superior intelligence, even to the level of Victor Frankenstein himself. This is mostly due to the James Whale classic Frankenstein (wr. Garrett Fort and Francis E. Faragoh/dir. James Whale) where the monster is portrayed as an inarticulate imbecile. This might have been done to enhance the frightening unpredictability of the monster, but more likely because any hint of intelligence was usually jeered at by American audiences. In the process, the depth of humanity embodied in the monster was completely lost in the childish actions of a simpleton. In the film, the killing of the little girl was accidental, but in the book, the killing of Frankenstein’s relatives was very much deliberate; revenge for Victor Frankenstein’s refusal to acknowledge his responsibility toward his creation. The monster, as Shelley saw it, was as grotesque internally as externally; his murderous psyche the result of his creator’s callous indifference.

The original victim of such careless adaptations is, of course, Mary Shelley and her depiction of Frankenstein’s monster. Almost everyone who reads the book is surprised to learn that the monster is of superior intelligence, even to the level of Victor Frankenstein himself. This is mostly due to the James Whale classic Frankenstein (wr. Garrett Fort and Francis E. Faragoh/dir. James Whale) where the monster is portrayed as an inarticulate imbecile. This might have been done to enhance the frightening unpredictability of the monster, but more likely because any hint of intelligence was usually jeered at by American audiences. In the process, the depth of humanity embodied in the monster was completely lost in the childish actions of a simpleton. In the film, the killing of the little girl was accidental, but in the book, the killing of Frankenstein’s relatives was very much deliberate; revenge for Victor Frankenstein’s refusal to acknowledge his responsibility toward his creation. The monster, as Shelley saw it, was as grotesque internally as externally; his murderous psyche the result of his creator’s callous indifference.

This might have been done to enhance the frightening unpredictability of the monster, but more likely because any hint of intelligence was usually jeered at by American audiences.

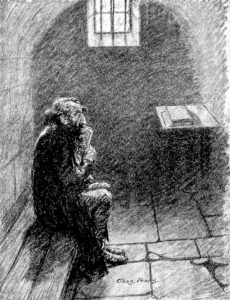

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle has also been one of the most aggrieved parties in this public domain free-for-all, where his Sherlock Holmes character has been distorted into the likes of Benedict Cumberbatch’s Holmes in the BBC/PBS production of Sherlock (cr. Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat) set in modern day London, to the gender switched Netflix production of Enola Holmes (wr. Jack Thorne/dir. Harry Bradbeer). Spoofs of the characters Doyle created are fair game, I suppose, though some are offensive for another reason: they simply weren’t funny. Will Ferrell’s tired rendition of the man-child in Holmes and Watson (wr./dir. Ethan Cohen) certainly fits into that category. No adaptation could be more offensive than Robert Downey, Jr’s Americanization of Holmes in Sherlock Holmes (2009) (wr. Michael R. Johnson, Anthony Peckham and Simon Kinberg/dir. Guy Ritchie), where the villains are turned into comic book super-villains, forcing Downey’s Holmes into the mould of silly comic book super-heroes that have become the actor’s current claim to fame.

Even Steven King is guilty of misused Doyle’s famous character when he quotes Holmes in his novel The Outsider. “Eliminate the impossible,” Holmes famously said. “Whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” But in this case, King uses this to justify belief in the supernatural. The acclaimed author took it to mean that if you can’t immediately explain something, then it has to be ghosts (or in this case, Outsiders). Conan Doyle would have been appalled, even given his belief in garden ferries. The one thing that Conan Doyle insisted Holmes not believe in was the supernatural. Sherlock Holmes is, at its best, a celebration of intellect over brawn, where there is little doubt that mind will triumph over matter; the ultimate vindication of the scientific method. Any other message would be a betrayal of the material.

Conan Doyle would have been appalled, even given his belief in garden ferries.

The pinnacle of faithful adaptations of Conan Doyle’s classic character would have to be Jeremy Brett’s wonderfully eccentric performance in the Grenada Television series The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1984, cr. Michael Cox),(2) His portrayal focused on Holmes as an impassioned advocate of the scientific method, despite being an eccentric drug-addled bachelor who barely tolerated the eccentricities of others. This was true to the novels, and the series was much better for it.

An often-ignored example of this kind of abuse is H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, a classic story of how our fate is bound to the whims of nature. In the book, our unnamed narrator (a British every-man) witnesses the destruction of his world by hostile forces beyond his imagining. He sees that where our best weapons of war have failed to protect us, a tiny, insignificant microbe saves the day. An instructive episode in the text is a chapter that reflected Wells’ own atheism. When a priest’s religious fervor threatens his life, our hero beats him to death with a shovel. Of course, this would never play well with American audiences. In the 1955 film version (wr. Barré Lyndon/dir. Byron Haskin), that priest (now named Pastor Collins and played by Lewis Martin) is transformed into a religious martyr when he is killed by the invaders. In the 2015 adaption (wr. Josh Friedman and David Koepp/dir. Steven Speilberg) the priest has been replaced by an unstable, evangelical former ambulance driver called Harlan Ogilvy (played by Tim Robbins). Given Wells’ stated religious beliefs, he certainly would have objected to both interpretations of the character, though he might have agreed that religious belief in all its forms is a kind of mental illness.

But even when the author is involved with the production (and sometimes well paid), there is no guarantee that the authorial intent will be preserved. In an unscrupulous ‘bait and switch’, many titles are not even related to the alleged source material. Notoriously, the film The Birds (wr. Evan Hunter/dir Alfred Hitchcock) has little to do with the novel by Daphne du Maurier on which it was purported to be based. Bladerunner (wr. Hampton Fancher and David Peoples/dir. Ridley Scott) is based on Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep by Philip K. Dick, but the title is from the book The Blade Runner by Alan E. Nourse, which is actually a story about teenagers smuggling medical equipment into a post-apocalyptic New York City. In the 1997 film adaptation of Carl Sagan’s novel, Contact, (wr. James V. Hart and Michael Goldenberg/dir. Robert Zemeckis) the religious character of Palmer Joss (played by a smirkingly superior Matthew McConaughey) was turned from an anti-science fanatic into a sympathetic love interest for Jodie Foster’s Ellie Arroway. Judging by Sagan’s other books, including The Demon-Haunted World (1995), it’s unlikely he would have had much sympathy for such a character, never mind making him one of the heroes of the story.

Palmer Joss was turned from an anti-science fanatic into a sympathetic love interest for Jodie Foster’s Ellie Arroway.

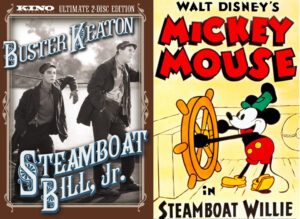

This is the problem when dealing with people who have no intellectual or moral obligation to the authorial intent of the material they are adapting. The heart of the matter is that huge multi-national corporations are now cashing in on someone else’s intellectual property, a cardinal sin in today’s corporate environment. Disney, the worst offender of them all, fights the hardest to prevent their own intellectual property from falling into the public domain. And the reason is simple: They certainly don’t want anyone bastardizing (or profiting from) their intellectual property. (3) Never mind that their signature character, Mickey Mouse, was made famous in a blatant rip-off of Buster Keaton’s character from Steamboat Bill, Jr. (wr. Carl Harbaugh/dir. Charles Reisner) combined with various racist blackface cartoon characters.

This is the problem when dealing with people who have no intellectual or moral obligation to the authorial intent of the material they are adapting. The heart of the matter is that huge multi-national corporations are now cashing in on someone else’s intellectual property, a cardinal sin in today’s corporate environment. Disney, the worst offender of them all, fights the hardest to prevent their own intellectual property from falling into the public domain. And the reason is simple: They certainly don’t want anyone bastardizing (or profiting from) their intellectual property. (3) Never mind that their signature character, Mickey Mouse, was made famous in a blatant rip-off of Buster Keaton’s character from Steamboat Bill, Jr. (wr. Carl Harbaugh/dir. Charles Reisner) combined with various racist blackface cartoon characters.

I’m willing to bet these people hardly offered a polite hello to the hundreds of Bob Cratchits who toiled over their computer stations into the wee hours creating the film.

Dickens’ intended message in A Christmas Carol could not be more clearly stated, and yet that obvious cautionary admonition is lost in the noise for the most part. The problem is that many of these adaptations are hardly created for someone in a meditative mood.

Needless to say, the idea that Netflix and Apple+ would expend millions of dollars to produce a cautionary tale about putting consumerism before spirituality is a bit disingenuous. Did the producers of Scrooge: A Christmas Carol really give much thought to the underpaid animators who slaved ungodly hours to produce their attempt at a Christmas classic? I would hardly think so. I’m willing to bet these people hardly offered a polite hello to the hundreds of Bob Cratchits who toiled over their computer stations into the wee hours creating the film. I’m not saying the result wasn’t somewhat entertaining in a diversionary kind of way. But the content seemed specifically designed to ensure the audience didn’t have time to meditate on Dickens’ original message, or the hypocrisy of the filmmakers.

***

1) – Apparently this was Humphrey Bogart paraphrasing Goldman. The real quote from Goldman went something like: “Messages? Messages? From Western Union you get messages. From me, you get pictures.” Not as pithy, but certainly sounding more like Goldman than Bogart.

2) – Followed by the later series The Return of Sherlock Holmes (1986), The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes (1991) and The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1994). The remaining Holmes novels and short stories were unfortunately never filmed due to the death of Jeremy Brett in 1994.

3) – Though it’s hard to think of any way to bastardize a film like ‘Song of the South (wr. Morton Grant, Bill Peet et.al./dir. Harve Foster and Wilfred Jackson).

***

Scrooge: A Christmas Carol (2022)

Runtime: 1 hour 36 minutes

Distributed by: Netflix

Direction by: Stephen Donnelly

Written by: Stephen Donnelly

Based on Scrooge (1970) (wr. Leslie Bricusse/dir. Ronald Neame)

Starring Luke Evans, Olivia Coleman, Jonathan Pryce and Jesse Buckley

860 total views, 1 views today