Oppenheimer and the Legacy of Genius

An essay by John Burke

***

“(They need us) … until they don’t.”

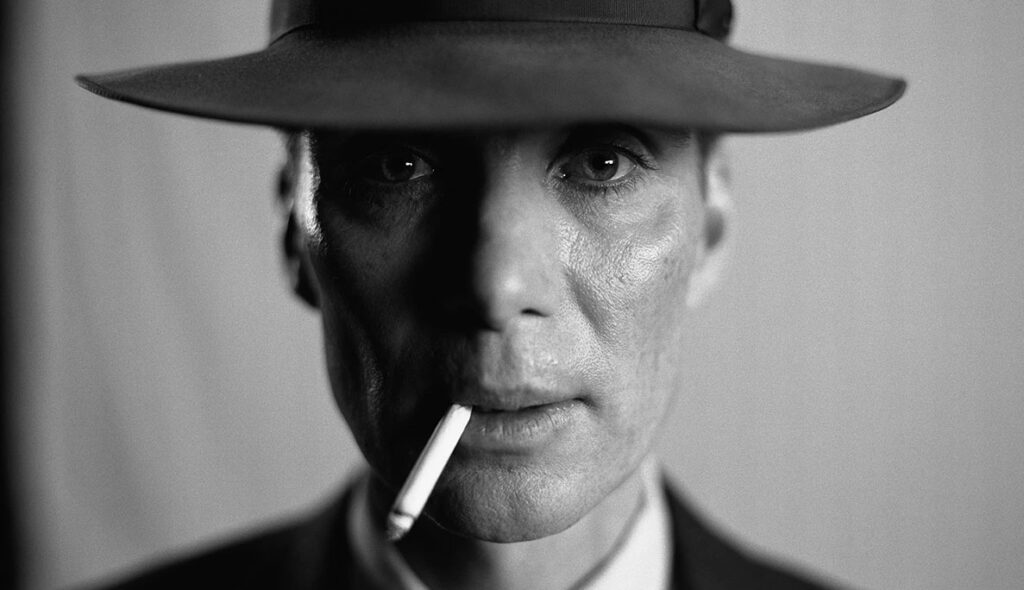

– J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy)

***

Any scientists involved in any kind of significant break-through would do well to be mindful of the above quote. Probably all creative innovators have felt the sting of this type of rejection at some point or another. Whether working for corporations or governments, democracies or dictators, most scientists are well aware that there will be an inevitable point where they are no longer needed. Harsh reality proves the lust for power has always fed on innovation and innovators rarely have any say in how their work is utilized. The creation of the first nuclear weapon is no exception.

With the release of Christopher Nolan’s epic biographical film Oppenheimer, the events surrounding the creation of the world’s first nuclear weapon have again been dramatized. Unlike previous public examinations of the events, this wasn’t precipitated by the sudden release of classified materials or the death of one of the principals, but an on-set gift from an actor (Robert Pattinson) to his director (Nolan) during a break in filming Tenent (wr./dir Christopher Nolan). According to Wikipedia, the gift was a bound copy of the speeches of physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer.

This steered Nolan into investigate Oppenheimer’s life, leading him to American Prometheus: the Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the 800 page biography by researchers Kai Bird and Martin J Sherwin, on which he based the screenplay.

Having read some parts of this tome when it was published in 2005, I found the endless details of Oppenheimer’s life came across a bit like a sordid soap opera, dominated by salacious details of sexual affairs and political intrigue. This is always a danger with source material that focuses more on the minute details of the hero’s life rather than the reason why they are remembered in the first place. No human being’s reputation could survive such invasive deliberation. Yes, humans are complex, but a writer’s job should be to distil that person’s life into a digestible form of overall truth. In the effort to make the character more ‘textured’ and ‘complex’, the endless attention to Oppenheimer’s flaws only served to undermine the premise that he was a capable man of good intentions.

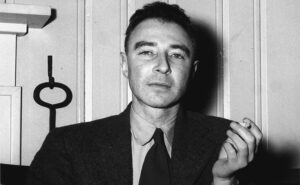

The first thing that must be understood about J. Robert Oppenheimer is that he was not the creator of the atomic bomb, or its father, or its builder. As far as I can tell, nothing of scientific value came from his published work. He did not discover any revelatory breakthroughs. His research did not break any new ground. He (like Einstein) certainly wasn’t the greatest mathematician. He didn’t directly contribute to the theoretical underpinnings of how the bomb worked. He didn’t split the atom. He didn’t develop any significant insights into quantum mechanics. And, unlike many of the scientists who worked under him, he never won a Nobel Prize.

When physicists Edward Teller accused Oppenheimer of being more a bureaucrat than a scientist, he certainly hit close to the truth.

My intention is not to dismiss the man, but to clarify why he was important. When physicists Edward Teller accused Oppenheimer of being more a bureaucrat than a scientist, he certainly hit close to the truth. Oppenheimer’s task was one of the less glamorous but equally important cornerstones of science: to confirm what others have discovered and summarize its significance. Oppenheimer was in a unique position to interpret the latest research for those who could never understand its implications. His European education allowed him to study under some of the most innovative theorists the world has ever known, including the brilliant theoretical physicist Niels Bohr.

He understood the latest theories of quantum mechanics, largely unknown in the US at the time, mostly due to Einstein’s stubborn resistance to the idea. Einstein’s insights into the mass/energy equation were enough to hint at the creation of a bomb, but he was spectacularly wrong about quantum mechanics and the nature of things at the atomic level. Oppenheimer’s job was to correct that. With his deep knowledge of both Einsteinian physics and quantum mechanics, Oppenheimer was the perfect individual to translate the ‘new’ physics into a practical reality.

***

Quantum mechanics is the ‘fire’ stolen from the gods as referenced in the book title American Prometheus. To this day, we still don’t know exactly why E=mc2 and we might never actually know unless we can figure out the details of quantum mechanics. But, despite having only a partial understanding of this science of the very small, we have been able to use what little we do know to create everything from atomic bombs to quantum computers. It’s entirely possible that some insight tomorrow might prove that none of what we thought we know about it is true. Every new discovery shows the world in a different light. Science is open ended, and has to remain so.

Few could question Oppenheimer’s essential role in the Manhattan Project. Certainly, he was critical in organizing the scientific and logistical effort. In other words, his genius was basically as a scientific administrator. But he was hardly the only one on the Manhattan Project. The other was General Leslie Groves, head of the Army Corps of Engineers, who actually provided the manpower and supervised the engineers who physically created the materials and who built the components of the bomb. By watching the movie, you would think the scientists themselves personally put the pieces of the Trinity bomb together and hung the bomb on the tower. The truth is that it was Groves and his engineers who actually built the ‘gadget’, a fact that seems to have been lost in Nolan’s effort. No one could know how an atomic bomb actually worked based on this film (though that was hardly the point) but, based on the movie alone, you suspect that Oppenheimer himself, portrayed as such a basket case, didn’t fully understand it, either.

As a pair, both Groves and Oppenheimer resembled the results of their work. In a different take on the story, the designations placed on their creations could symbolize them as a Laurel and Hardy like duo who struggle against the madcap world that surrounded them, pitting the idealism of the scientists against the realism of brute force military procurement. Groves was close to the dimensions of Oliver Hardy, matching the proportions of the plutonium-based ‘Fat Man’ bomb, while Oppenheimer was much thinner than Stan Laurel, matching the long, thin proportions of the uranium-based ‘Little Boy’ bomb. Anyone up for a prequel to Dr. Strangelove (wr. Terry Southern/dir. Stanley Kubrick)?

Oppenheimer and Groves were certainly not the only ones responsible for the creation of the bomb. There was Ernest Lawrence, Werner Heisenberg, Niels Bohr, Vannevar Bush, James Chadwick, James Conant, Enrico Fermi, Hans Bethe, and many, many more, including, let’s face it, Nolan’s antagonist Lewis Strauss. Nolan said that, once the atom was split, almost every physicist worth his salt understood within minutes that this could be the makings of a bomb. The difference was that Oppenheimer, along with Groves, made it happen.

***

It would be a truism to suggest that the world’s best film makers have a flair for the dramatic. Christopher Nolan is one of those rare filmmakers capable of also making their films intellectually challenging. (1) This makes him perhaps the only filmmaker alive today capable of making a commercially successful film adaptation of American Prometheus. And in that respect, he succeeded, at least financially. The movie is like a hugely overblown indie film, a character study not seen from Nolan since his hugely successful 2000 indie film Memento. Now, whether the story added enough to the public discourse to make it worth the lavish treatment Nolan imparted on it is another matter.

On a visual level, Cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema displays his usual deft touch to the images on screen, handling those massive, noisy IMAX film cameras with a skill that seems superhuman. Still, I had hoped the black-and-white sequences would have displayed a little more art. I mean, how often does a cinematographer get to shoot in black-and-white film stock these days? Ironically, his least convincing imagery was the explosion of the Trinity bomb itself, which might have been due to Nolan’s insistence on using practical effects. Obviously, Nolan didn’t have the luxury of detonating a nuclear bomb for his movie, which necessitated the use of small-scale conventional explosives. Photographing small explosions in a way to make them seem like big explosions is a tried and true Hollywood tradition, and (due to the laws of physics) they invariably look fake. If it were not for the incredible sound effects, the Trinity explosion as depicted in the film would only be anti-climactic, especially since we never see the iconic mushroom cloud we all recognize. It’s a strange quirk of human perception that the grainy 35mm film of the real Trinity explosion featured in Trinity and Beyond (wr. Scott Narrie and Don Pugsley/dir. Peter Kuran) is far more menacing.

It’s a strange quirk of human perception that the grainy 35mm film of the real Trinity explosion featured in Trinity and Beyond is far more menacing.

Sometimes, the millions of dollars spent on ensuring the historical fidelity of a movie can be easily undone with a single incongruous detail. Remember that infamous scene in Ben Hur (wr. Karl Tunberg/dir. William Wyler) featuring a Roman slave wearing an expensive gold wrist watch? Unfortunately, the most distracting part of Oppenheimer was an unintended consequence of the large-screen format, in the form of the piercing of Cillian Murphy’s left ear, a detail that would hardly have been noticed in any other medium. There were even a few scenes where the close-ups were so extreme, the focus puller wasn’t always successful keeping the relevant details in focus, bringing even more attention to it. My estimation was that, on the IMAX screen, the piercing in Murphy’s ear was close to two inches in diameter. And yes, that is what I was thinking of at that point, and not the dramatic moment the director intended me to focus on. Otherwise cleaving to such technical detail only made the incongruous ear-piercing even more distracting. It wasn’t a good sign that this was the over-riding memory I carried out of the movie theatre.

Ruth De Jong’s production design was well below her usual standards, though to be fair she didn’t have very promising material to work with, given the settings and the time period. How could a film dominated by desert browns and dry wood, with the most expansive scenes shot in black-and-white, be expected to be in any way colourful? The lack of any saturated colour might have been a stylistic choice used to convey the time period, but I found any type of colour symbolism either lacking or too overwhelmed by other factors to be noticed. It’s too bad the film turned out to be a waste of her considerable talent.

As for sound, Oppenheimer suffers from the same fault as Bladerunner 2049 (wr. Hampton Fancher and Michael Green/dir. Denis Villeneuve), where the musical score overwhelms the movie at certain points, sometimes drowning out entire sections of dialogue with a cacophony of noise meant to enhance the emotion and meaning. Ludwig Göransson’s score bludgeons you over the head in an attempt to make you feel emotions that you don’t really feel. The experience made me nostalgic for the crisp clean scores of Jerry Goldsmith or John Williams, scores that complemented the existing emotions rather than trying to manufacture them with sheer volume. What’s more terrifying than the musical doublets of Jaws (wr. Karl Gottlieb/dir. Steven Speilberg) or the incessant crackle of the Geiger counters in Chernobyl (wr./dir. Craig Mazin)? Or the profound silence of space in 2001: A Space Odyssey (wr. Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick/dir. Stanley Kubrick)? I’m willing to admit this might have been the fault of the sound balance in the theatre, though it’s hard to believe since part of the $20.00+ ticket was for the sound experience.

The experience made me nostalgic for the crisp clean scores of Jerry Goldsmith or John Williams, scores that complemented the existing emotions rather than trying to manufacture them with sheer volume.

Oppenheimer’s run time could have been shortened considerably, especially in the first and last acts. Whether this was a reflection on abilities of the editor is hardly in question. Jennifer Lame is no slouch when it comes to cutting a film, starting her career as an editorial assistant for Sidney Lumet and Peter Jackson and of late managing to survive the editorial nightmare of Nolan’s Tenet. On that film, she replaced Nolan’s long-time editor Lee Smith, taking over the responsibility of managing the constant criss-crossed timelines. Was her attempts to introduce more significant female characters the cause of Oppenheimer’s (excuse the term) flaccid beginning and end? It’s possible, but it’s more likely the fault lies elsewhere.

Lately, writer/directors in particular seem to feel that every ounce of their creative juices must be faithfully displayed on the screen, regardless if it interferes with the storytelling. It seems a film is not considered serious unless it runs over-long. (2) Nolan in particular has been vocal about supporting theatrical releases, and yet he makes it near-impossible for the theatre owners to screen his films. As a movie, Oppenheimer definitely has a sense of overloaded self-indulgence, something to which Nolan is not usually susceptible. Juggling so many characters and so many plot lines required a torturous set-up that made the beginning a bit of a slog. And tying them up required an extended third act that seemed to never end. Nolan insisted the process of actually creating the bomb and detonating it was less dramatically important than the soap-opera of Oppenheimer’s betrayal by Strauss. When directors get too precious with their material, they have to trust their editors to trim the fat and the redundancies. But for editors, insisting on cutting out the director’s favourite scenes could lead them to the unemployment line. In the end, it’s the director’s decision, for better or worse.

I’m all for the ‘show-don’t tell’ ideal in film making for the most part, but in this case it runs very close to not succeeding.

Nolan indicated that he had written large portions of the screenplay in the first person, from Oppenheimer’s point of view. Such a conceit would explain why the audience was intended to accept the character’s allegedly naive view of the consequences of the Manhattan project, as well as the film’s dismissive attitude toward women. Depending solely on Oppenheimer’s internal struggle to drive the drama, Nolan was forced to use various metaphorical atom-like particulate visuals, as well as over-the-top music and extreme close-ups to display his angst. I’m all for the ‘show-don’t tell’ ideal in film making for the most part, but in this case it runs very close to not succeeding.

Nolan decided on the questionable necessity of portraying Oppenheimer’s childhood alienation during his school years. Other than introducing the character of Niels Bohr, to what ends was a mystery. So he was lonely at boarding school. I mean, what foreign student doesn’t feel alienated and alone? This sequence culminated in the poison apple episode, something both historically and dramatically problematic. Literalizing such an absurd tale only showed how preposterous it actually was. It didn’t serve to illustrate Oppenheimer’s eccentricity, only making the audience question his sanity. If it did happen in the manner portrayed in the film – and chances are it did not — it would be reason enough to revoke his security clearance. But, then again, the Sleeping Beauty reference (wr. Charles Perrault, 1697) would have been difficult for an over-the-top dramatist like Nolan to resist.

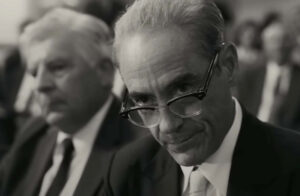

Nolan’s decision to focus on Oppenheimer’s POV was undermined by the necessity of putting us in the political back rooms with Senator Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) and his henchmen. Splitting the adversarial attack between the Senate confirmation hearing of Strauss and the AEC security clearance hearings of Oppenheimer only served to diffuse the peril. Both of these might well have been historically accurate, but I questioned the necessity of both being in the film. The AEC security clearance hearing could have only been a very boring affair in reality. It dominated later sections of the film, forcing Nolan to resort to spicing it up with dramatic pauses, over-the top music and awkward sex scenes.

The special counsel for the AEC, Roger Robb (played with calculated menace by Jason Clarke), is thrown into the mix with little introduction, playing for the ‘got-ca’ moment, guns blazing during the hearing, as if no one else knew about Oppenheimer’s background. But everyone knew, including the audience. Through much of the film, Oppenheimer’s affair had been dealt with and his communist background clearly explained. Recounting the incident in the hearing again seemed redundant. The ‘revelation’ felt a little wonky and ham-fisted. Perhaps, if the hearing had been used as a thread holding the film together, it might have cut back on the redundancies and justified its purpose.

The AEC security clearance hearing could have only been a very boring affair in reality … forcing Nolan to resort to spicing it up with dramatic pauses, over-the top music and awkward sex scenes.

Frankly, I wondered why the Strauss’ Senate committee hearing was worth the effort of its portrayal. Finding out Strauss instigated the AEC hearing could have been handled in that one excellent final scene where Strauss revealed himself, rather than the protracted character study of Strauss, someone whose name has thankfully faded into history. But, for an actor and a director, the character was just too good to discard. I believe it was Nolan’s intention to force the slight dodge that the audience wouldn’t realize Strauss’s full intentions until the end. It might have served the tension of the film better to have a more conflicted, less bad, bad guy right from the start.

It’s unfortunate that a large part of the beginning of the film was set aside to portraying the affair Oppenheimer had with psychiatrist Jean Tatlock, (played with erratic confusion by Florence Plug). Tatlock’s character is portrayed as little more than a politically naive, emotionally unbalanced woman. In reality Tatlock was a politically savvy and well educated psychiatrist who just happened to have political views that didn’t align with American societal and plutocratic ideals. There was little doubt Tatlock was a communist, but did that make her unbalanced? And were her mental problems really any worse than Oppenheimer’s? After all, didn’t Nolan portray him as so emotionally unbalanced he was willing to commit murder and almost succeeded? And yet there is the implication that Tatlock was somehow guilty of some greater crime, perhaps that of being an ‘emotional’ woman who kills herself over love.

Nolan uses Tatlock to introduce Bhagavad Gita, finding the book on Oppenheimer’s bookshelf and conveniently giving him the opportunity to read the quote for which he is most famous. “Now I am become Death, destroyer of worlds”. Nolan didn’t even bother to have Oppenheimer read the context of the quote, only the famous line. This felt like a huge coincidence since the scene takes place years before the Trinity test. And it seems gratuitous to place such a thing in a sex scene, as if it was some ham-fisted way of suggesting impotence. Or was it orgasm? As they sit naked on opposite sides of the room afterward, it certainly didn’t represent intimacy. Precisely why it was necessary to include these scenes is a mystery since they had little real impact on the story. Was Nolan concentrating on an ‘R’ rating for the controversy? Hard to tell.

The sterility of the cold, efficient sex scenes, and the repeated references to the bomb during them, are a little ‘on the nose’.

Whatever the reason, the ‘whores or saints’ view of women is in full force here. The only two female characters in the film are hardly there for any other purpose than to make it clear that Oppenheimer was a ‘lady’s man’. The sterility of the cold, efficient sex scenes, and the repeated references to the bomb during them, are a little ‘on the nose’. Not unlike those in Eyes Wide Shut (wr. Fredric Raphael/ dir. Stanley Kubrick), no one could describe them as being ‘sexy’ in any way. Nolan often focuses on stories that are set in worlds where men were almost exclusively the source of drama, worlds mainly populated only by men. The disintegrating bromance in Memento. The soldiers in Dunkirk. The magicians in The Prestigue. The superheroes and super villains in the Batman trilogy. These man-on-man confrontations are a common thread in almost all of his movies, with the women pushed to the side and minimized. And when featured, they are hardly flattered.

A good example of this is Oppenheimer’s alcoholic second wife, Kitty, played with delightfully stern disapproval by an under-utilized Emily Blunt. It beggars belief such a talented actor was wastefully relegated to essentially a background player for most of the film. Though Kitty does become more significant toward the end, mostly she’s written as a nagging, unpleasant wife goading her meek husband into action. Much of the suggestion of Oppenheimer’s naivety was based on her goading, with one withering glance at her husband during the AEC interrogation scene defeating our already emasculated hero. When one looks into it, the character of Kitty turns out to be far more interesting than the emotionally damaged Tatlock and a better decision would have been to forsake one for the other. Perhaps it might have been far more interesting to see that sex scene.

As portrayed, Kitty Oppenheimer believed that her husband wanted to be torn down, as evidenced by the portrayal of his shabby self-defence during the AEC hearing. Was Nolan suggesting his guilt prevented any articulate defence of his real crime, which was his naive belief in the inherent goodness of his government? What I found really hard to accept is that Oppenheimer, a notorious egoist, stammered and fumbled when he was forced to justify his choices to a petty government lawyer. He had literally faced down the fires of hell developing the bomb and yet he trembles before the board of review without a coherent argument and absolutely no moral outrage at the affront of such accusations. It just didn’t add up for me.

This has become a sort of niche Hollywood trope, where a scientist who has up to now been articulate and passionate becomes inarticulate and flustered when questioned by a non-scientific ‘authority’. In the movie Contact (wr. James Hart and Michael Goldenberg/dir. Robert Zemeckis) the character of Ellie Arroway (in an almost giddy performance by Jodie Foster) crumbles when confronted by idiotic arguments by government officials bent on taking advantage of her discoveries. Similarly, in Don’t Look Up (wr. Adam McKay and David Sirota/dir. Adam McKay), doctoral candidate Kate Dibiasky (a quirky Jennifer Laurence) becomes an inarticulate freak when confronted by vacuous reporters. It’s becoming the norm that intelligent, thoughtful characters, mostly scientists, revert to anti-social idiots when the story requires it. Rather than suggesting character complexity, it smacks of lazy writing.

Oppenheimer is at least as interesting for what the filmmaker opted to leave out.

Oppenheimer is at least as interesting for what the filmmaker opted to leave out. Distilling a story like American Prometheus into a screenplay requires making a lot of these choices. It’s not like there weren’t tons of far more interesting scenes Nolan could have chosen to render.

Given that physicist Klaus Fuchs played such a huge role in Oppenheimer’s humiliation, it made no sense that he barely existed in the film except for a bit of throw-away dialogue. Though he didn’t actually assign Fuchs to the project, Oppenheimer made a point of keeping all of the scientists on the project as confidants. It seems unlikely Fuchs would be the one who escaped such attention. Could Oppenheimer have suspected what Fuchs was up to? It’s a fair question, certainly more compelling than whether his former lover was a communist. More could have been made of the other people who could have helped with the bomb but refused. According to physicist Phillip Morrison (an accused Communist sympathizer), after the war Oppenheimer was hardly empathetic to their stance, and he even turned in a few of them during the Communist witch hunts in the 1950s. Nolan would have done well to focus on exactly why Physicist Niels Bohr (played with proper British condescension by Kenneth Branagh) was important to the development of the bomb, or perhaps have Oppenheimer turn to Bohr (his former teacher and mentor, allegedly representing his conscience) for advice, rather than Einstein (3)

Or perhaps Nolan could have illustrated how difficult it was to explain complicated concepts to the politicians and generals who would have to marshal the resources to pay for it. I waited for the scene where Oppenheimer was forced to explain the concepts behind the bomb to Lewis Strauss (a staunch Einstein follower who also questioned quantum mechanics), but unfortunately the delicious scene never materialized. Oppenheimer’s condescension would have been a far better motive for Strauss’ vendetta.

Oppenheimer’s condescension would have been a far better motive for Strauss’ vendetta.

Casting Cillian Murphy as the titular character was a masterstroke, possibly the only thing that saved the movie for me. Few other actors are capable of such restraint and yet still convey real emotion. He rarely resorts to affectation to make his point. Others have made valiant attempts at this, like Ryan Gosling in Drive (wr. Hossein Amini/dir. Nicolas Winding Refn), Bladerunner 2049 (wr. Hampton Fancher and Michael Green/dir. Denis Villeneuve) and First Man (wr. Josh Singer/dir. Damien Chazelle), and Brad Pitt in Ad Astra (wr. Ethan Gross/dir. James Gray). But in this case, Murphy succeeds. Though he doesn’t particularly look like Oppenheimer, he seemed to channel the physicist without doing an impersonation. There was never a point where an audience member would question if they were watching Oppenheimer himself on screen.

The same couldn’t be said for the secondary and supporting cast. There are an inordinate number of small roles, maybe too many, populated by too recognizable faces. This created the expectation that these characters are much more significant to the story than they really are. There was definitely a point where I was questioning the decision to have this endless parade of recognizable faces in positions usually filled by solid character actors or up-and-comers. (4) Don’t get me wrong, it is fun to find un-credited cameos in movies. Gary Oldman as President Truman was a good choice. Sure, I can understand the appeal of bigger name actors wanting to be invited to the party, even if in minor roles. But when you add Matt Damon, Rami Malek, Kenneth Branagh, Josh Hartnet, Matthew Modine, Gary Oldman and Casey Affleck to the mix, it gets pointless and distracting, pulling me out of my suspension of disbelief.

The primary antagonist turns out to be Lewis Strauss, though this isn’t clearly evident at the outset. At his slimy best since he quit drugs and went superhero, Robert Downey, Jr. plays Strauss as a straightforward antagonist, a vindictive politician who gets his comeuppance in the end by being denied Secretary of Commerce in the Eisenhower administration. (Strangely, as the primary antagonist, Straus, is almost never in the same room with the protagonist.) But, as usual, it wasn’t that simple. I’m hardly one to defend right-wing conservative religious politicians (Strauss was a devout Jew) but his very human reaction to his ambitions being thwarted was understandable. After all, he was forced out of a very exclusive nuclear club he helped create, essentially because he wasn’t smart enough. Credit where it is due, Strauss did much to secure funding for the Manhattan Project, as well as fighting hard for his government to recognize the persecution of Jews by the Nazis. And his opinion of Oppenheimer as a lapsed Jew with questionable moral and political principles wasn’t that far from the mark.

And his opinion of Oppenheimer as a lapsed Jew with questionable moral and political principles wasn’t that far from the mark.

Strauss gave Downey a lot of material to work with, possibly more valid material than Oppenheimer provided for Murphy. I wouldn’t be surprised by a supporting actor nomination for his work here. But without a thorough bit of research, you would never know any of Strauss’ back story, since little of it made it into the final film. The idea that he blamed Oppenheimer for Einstein’s slight was a little thin to say the least, especially since it was based on an incident fabricated for the movie. (3) Yes, his vilification of Oppenheimer was unfair, but it did ultimately backfire, making for a satisfying end to the movie. But I can’t help but wonder if it would have been more satisfying if we had learned more about him.

I can’t say much in favour of the portrayal of General Leslie Groves, played for comic relief by a miscast Matt Damon. The suggestion that Groves did not understand the risk of igniting the atmosphere with the Trinity test is a bit cartoonish, robbing the formidable personality of the real General Groves. Damon is a good actor, but I have never seen his acting range come near the gravitas need to properly give Groves his due. I’m not sure why Nolan chose to minimize this important relationship in favour of the sexual affairs and political intrigue. After all, it was Groves who chose Oppenheimer and vigorously defended him throughout the development of the bomb. But in Oppenheimer, Groves was relegated to just another of the people who turned on our hero.

I’m not sure why Nolan chose to minimize this important relationship in favour of the sexual affairs and political intrigue.

An interesting supporting character is Edward Teller (in a somewhat uniquely accented performance from writer/director and part-time character actor Benny Safdie). Nolan hinted at Teller’s importance in the development of the Hydrogen bomb and the escalation of the Cold War that followed.

To his credit, Safdie did display some of the physicist’s belligerent hawkishness toward anyone who opposed his plans for the Hydrogen Bomb, including the ‘cry-baby’ Oppenheimer would eventually become. In the trailer of the movie much is made of the fact that the scientists involved could not be certain that the Trinity test would not ignite the atmosphere and destroy all life on earth. It was Teller’s questionable calculations that predicted the odds of setting the atmosphere on fire as being ‘almost impossible’, highlighting the fact that scientists are never certain of anything. As soon as anything becomes unquestioning and dogmatic, it ceases to be science. And if there was one thing that Teller eventually became it was dogmatic. (5) There’s just enough insanity there to make a movie all its own.

***

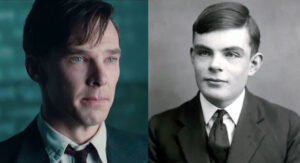

Oppenheimer begs comparison to two other films with very similar themes, Fat Man and Little Boy (wr. Bruce Robinson/dir. Roland Joffe) and The Imitation Game (wr. Graham Moore/dir. Morten Tyldum). Fat Man and Little Boy opted for a more straight-forward Hollywood depiction of the events, hardly a condemnation considering the inherent drama of possibly the most significant event in human history. Paul Newman’s take on Groves in Fat Man and Little Boy was certainly more satisfying in a Hollywood sort of way, unfortunately overshadowing Dwight Schultz, who played Oppenheimer.

This was 1989, so, of course, the filmmakers chose not to venture into any suggestion about Oppenheimer’s sanity, choosing only to portray the situation where he was forced to decide between two equally bad choices. The period demanded overt dramatic licence, mostly embodied in the fictional character of Michael Merriman (played by John Cusak), who’s death provides the karmic retribution for the bomb’s development. (6) The filmmakers decision to lean into the tragic/romantic storyline unfortunately undermining the gravity of the chilling debate over whether the scientists bear any responsibility if the bomb is used. In that respect, Oppenheimer offered a more credible conundrum for the main character, even if it was unnecessarily diffused by the focus on his faults.

It’s easier to compare Oppenheimer to The Imitation Game, though that might be somewhat unfair, since they are very different films in style and content …

It’s easier to compare Oppenheimer to The Imitation Game, though that might be somewhat unfair, since they are very different films in style and content, with the more main-stream approach of The Imitation Game making the film more entertainment than work of art. Still, both films are dependent on a certain trope that implies the mental deficiencies of certain scientists are the source of their genius. Nolan’s fetishist attention to Oppenheimer’s eccentricities couldn’t help but reference Benedict Cumberbatch’s on-the-spectrum performance as Alan Turing. Such tropes are easier to portray, rather than having to examine the real source of the genius – hard mental work. (7) But depicting such endeavours like ‘thinking’ is notoriously un-cinematic. In this case, I think The Imitation Game was more successful in portraying the thinking process by artificially linking revelations to the everyday life and problems of the character, including his attempts to disguise his homosexuality.

The conviction and suicide of, arguably, England’s most essential protector, Alan Turing, had a far greater impact on the world than the revoking of Oppenheimer’s security clearance by the AEC. Losing his security clearance didn’t quiet Oppenheimer in any way, and in fact might have made him more influential than he would have been otherwise.

Turing, on the other hand, was silenced by his persecution and untimely death, never witnessing his oversized influence on our world. Who knows what he could have accomplished if he had been supported rather than persecuted? What kind of an ambassador for peace would he have been had he been allowed to express his opinions freely? Though what happened to Oppenheimer pales in comparison to the invasive persecution of Alan Turing, the result was the same. The work they started was usurped by those who undeservedly elevated themselves at their expense. Once the political spin was applied, it was decided that their country didn’t need them anymore. They were deemed a ‘cry-babies’ and put in their place. In the end, both Turing and Oppenheimer were vindicated, their persecution acknowledged and apologies offered. But that was meaningless. The damage had been done.

Nit-picking aside, Oppenheimer is an astonishing achievement in film making, shot on a notoriously difficult format with exceptional skill.

Nit-picking aside, Oppenheimer is an astonishing achievement in film making, shot on a notoriously difficult format with exceptional skill. But knowing some of the more significant events of the story were ignored in favour of playing up the lead character’s flaws made it a lot less entertaining than I had hoped. Going into Christopher Nolan’s epic with a small amount of previous knowledge about the scientific administrator and what he accomplished, I left with few new insights into his character. The movie is a very good bookend to The Imitation Game, providing a perspective that the other film could never achieve. Though there was never a point where I regretted seeing Oppenheimer on the big (read: giant) screen, the story itself, as told, didn’t really justify the trip to the theatre. I actually look forward to re-watching the film on my smallish 60” television, where the sound won’t batter me into submission and I can actually hear what the actors are saying. Only then can I really assess whether a film that focuses on only the flaws of such an exceptional person would be interesting to watch. Nolan seemed too intent on making us believe in Oppenheimer’s naivety. He tells us ‘Oppie’ regretted the danger he had helped release on the world. That’s hardly a revelation. But Nolan wants you to understand that he REALLY regretted it so very much. I frankly found the premise a little hard to swallow.

As atrocities go, the impersonal death of 100,000 Japanese civilians pales in comparison to the very personal efforts of a few Nazi Party bureaucrats with some poison gas and a cremation oven.

The question of Oppenheimer’s late developing morality has been debated endlessly. But to suggest he was politically naive would be a big stretch. I doubt there was ever a moment where he did not know full well this required the extermination of hundreds of thousands of civilians. As the movie states, the fire-bombing of Dresden and Tokyo killed more people than the bombing of Hiroshima. What difference does it make to the dead how they were killed? It’s hard to imagine that Oppenheimer ever forgot the purpose of his mission, that of creating a ‘gadget’ capable of ending the Nazi scourge that had plagued Europe for the past decade. As such, it’s hard not to think that revenge played a factor in Oppenheimer’s motivations during the Manhattan project, and, to a point, that would be a reasonable reaction. For a Jew like Oppenheimer, robbed of the opportunity to punish Nazi Germany, the ‘Japs’ were necessarily a poor substitute. After all, as atrocities go, the impersonal death of 100,000 Japanese civilians pales in comparison to the very personal efforts of a few Nazi Party bureaucrats with some poison gas and a cremation oven.

Let’s not kid ourselves into believing Oppenheimer was any kind of a hero. At no point did he suggest not using the bomb to end the war. Though he was an unquestioning patriot, he understood the power such a weapon represented; that it would make America the unquestioning ruler of the world, or so they dreamed. For Truman and Strauss, the idea that it was about anything other than megalomania and world domination is delusional. And the reason for communist paranoia in the 1950s was because there was an element of American society who saw the danger of world domination by anyone. No such question arose when it came to the idea that America deserved such a position, and anyone who questioned that was considered a traitor.

It might be interesting to speculate what might have happened if people like Oppenheimer would have been allowed to speak their minds, but the truth is that once Russia detonated their own bomb, no amount of reasoning by ‘crybaby’ scientists would have stemmed the tide of the resulting Cold War. As such, Oppenheimer could never be taken seriously as a pacifist. His about-face after the war would have prevented him from having any real impact on the development of the cold war, whether he had kept his security clearance or not.

Physicist Joseph Rotblat deservedly won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1995 in his stead. After Germany surrendered, Rotblat refused to work on the Manhattan Project any longer, later organizing the 1957 Pugwash Conference on nuclear disarmament. It was no coincidence that the town of Pugwash, Nova Scotia, where the international conference was held, is only an hour’s drive north of Halifax; a city that knew first-hand the consequences of an explosion of that scale. (8)

***

You could accuse Turing and Oppenheimer of being naive by today’s standards, but that wouldn’t be fair or even accurate. No one could have foreseen the effects of miniaturization, whether in bombs or computers. Even the best science fiction writers of the day saw powerful computers being the size of cities and bombs requiring gigantic airplanes and rockets to deliver them. The atomic bomb, once a weapon of superpowers, is now a device that can be created for a few million dollars and fit into a suitcase, affordable by any reasonably ambitious dictator. The creators of the bomb could have never seen the threat of suicide bombers delivering an atomic bomb into an unsuspecting city during peace time. Today, our greatest nightmare is a terrorist with a cell phone and a suitcase bomb, sealing the legacy of both Oppenheimer and Turing in one stroke.

Our only ray of hope is if Artificial Intelligence really is superior to us, not just intellectually but morally.

Even fewer could have recognized that the code breaking effort at Bletchley Park during the war years would eventually rival nuclear weapons as an existential threat to humanity, not even Turing himself. It now seems that the fruition of Alan Turing’s work, the realization of machine intelligence, has become inevitable. But the people who have built upon his work are now hidden behind anonymous corporations. There is no articulate spokesman advocating for the cautious use of these discoveries, someone who understands the imminent dangers of what’s being created. The fact is that with Turing’s thinking machine, it could only be a matter of time before even more imaginative methods of destroying ourselves come along. Our only ray of hope is if Artificial Intelligence really is superior to us, not just intellectually but morally. Because if we teach AI only what we know, then there’s nothing to prevent it from behaving just as badly as we have. If AI can’t be taught to be moral, then Turing’s ‘bomb’ might well be far more destructive than Oppenheimer’s ‘gadget’.

***

1) A friend of mine described his previous effort, Tenet (wr./dir. Christopher Nolan) as a mind-fuck without the orgasm.

2) I’m talking about you, James Cameron, and you, Quentin Tarentino. I don’t think I’m the only one who misses the filmmaking economy of Terminator (wr. James Cameron and Gail Anne Hurd/dir. James Cameron) and Reservoir Dogs (wr./dir. Quentin Tarentino).

3) I understand that Oppenheimer’s interaction with Einstein in the film is one of the few outright fabrications, the gist of it having been an exchange between Oppenheimer and Arthur Compton, head of the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago, who was instrumental in the extraction of uranium and plutonium from raw ore. Speaking to the New York Times, Nolan said that he changed Compton to Einstein because Einstein “is the personality people know in the audience.” Other than cowing to the audience, he doesn’t really justify the change in any other way, thinking the audience wouldn’t understand who Compton might be. Such catering belies all his efforts to make the movie as realistic as possible. Einstein has been so badly portrayed in so many films by now that even the most sincere portrayal borders on parody. Einstein essentially warns Oppenheimer that he will never be forgiven for succeeding. Attributing such profound wisdom to Einstein was unnecessary, even cartoonish, especially factoring Einstein’s pacifism and his opposition to the bomb’s development. Oppenheimer’s opinion of Einstein, expressed earlier in the film, was that the man’s ideas were 40 years out of date. I think replacing Compton with Einstein was little more than catering to the idiot brigade. The thing is that Nolan already had an existing character in which Oppenheimer could have confided, in the person of his friend and former teacher Niels Bohr.

4) Come on guys, give the little guy a break once in a while. Where would Harrison Ford be today without his bit part in Apocaylpse Now (wr./dir Francis Ford Coppala)?

5) Teller would have gladly backed the use of nuclear weapons in Korea and Vietnam if General MacArthur had been able to convince anyone it was a good idea. And he cooked up hundreds of non-military uses for nuclear materials, dismissing the danger of such materials landing in the wrong hands as well as the long-term effects of radiation. He convinced Ronald Reagan that nuclear missiles could be repelled by the right anti-weapons systems, making the likelihood of a nuclear strike from Russia (again) ‘almost impossible’ and resulting in the ineffective and hugely expensive Strategic Defence Initiative. He also suggested the use of nuclear weapons in commercial mining and terra-forming the Earth. He even blamed Jane Fonda in China Syndrome (wr. T.S. Cook and Mike Gray/dir. James Bridges) for his heart attack.)

6) The filmmakers did not portray the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki either.

7) I’m reminded of a very funny scene in the television show The Big Bang Theory (cr. Chuck Lorre and Bill Prady) where Sheldon Cooper (Jim Parsons, another victim of ‘mentally challenged scientist’ trope) and Raj ( Kunal Nayyar, ditto.) are working on a supposedly difficult mental problem. The comedy comes from the characters being shown virtually static as they think, but the drama was comically depicted by the eccentric slow-motion camera work accentuated by the power ballad Eye of the Tiger (comp. Frankie Sullivan and Jim Peterik/Survivor) played over it.

8) In 1917, most of the downtown core of Halifax, Nova Scotia was flattened by the largest man-made explosion ever recorded before Hiroshima. After a collision, a munitions ship exploded killing more than 3000 people and blinding thousands of others with flying glass. It was good that Nolan found the time to at least a mention the Halifax explosion, though the sequence where it was discussed hardly clarified the significant role it played in the deployment of the bomb.

***

Oppenheimer (2023, 3hrs)

Writer/Director: Christopher Nolan

Cinematography: Hoyte van Hoytema

Cast: Cillian Murphy, Robert Downey Jr., Emily Blunt, Florence Pugh, Matt Damon

Release date: 21 July, 2023

5,238 total views, 1 views today