An Essay by John Burke – December 8, 2013

In response to the essay: How to Put God in a Movie*

By Albert J. Bergesen, Professor of Sociology – University of Arizona

***

Many people who are unfamiliar with the genre think that Science Fiction, whether in books or movies, is sterile and Godless. Many are ignorant of the essential part spirituality has played in the concepts of morality featured in many of the most popular Science Fiction stories. The problem seems to lie with the prejudicial concept of God in the Judeo-Christian tradition. There are any number of manifestations of God, and spirituality in general, in many (but certainly not all) Science Fiction.

The problem seems to lie with the prejudicial concept of God in the Judeo-Christian tradition.

The most famous non-Christian manifestation of God in movies is probably ‘the force’ in ‘Star Wars’ (wr./dir. George Lucas), but this certainly isn’t the only example. In ‘The Matrix’ (wr./dir. by the Wachowski brothers), Thomas Anderson (Keanu Reeves) is resurrected from the dead to become Neo, a God figure not unlike Jesus. In ‘Dune’, a series of novels written by Frank Herbert, Paul, the orphaned son of a revered leader from the heavens, becomes the messiah (Mahdi) of prophesy predicted by the Fremen, desert dwellers of the planet Dune (Arrakis).

In the 1951 movie ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’, (wr. Edmund North/dir. Robert Wise) a Jesus figure (Michael Rennie) descends from the sky preaching of peace. (The man is literally named Carpenter.) When he is killed by American soldiers, he is resurrected by a God (in this case portrayed by a monstrous robot), and warns the people of Earth about their violent ways before he leaves, ascending slowly into the sky. In the wildly popular film ‘Avatar’ (wr./dir. James Cameron), the religion of the primitive Navi is a stand-in for any one of a number of Mother Earth religions that warn of environmental degradation. These and many other examples of spirituality in Science Fiction can run the gamut from Orthodox Judean mono-theism to Wiccan pan-theism to Buddhist enlightenment. It seems only those who choose to look at these stories from a strict perspective of unwavering Christian faith that have a problem seeing the spiritualism evident everywhere in Science Fiction.

A good example of this kind of Judeo-Christian religious prejudice can be seen in the essay ‘How to Put God in a Movie’* published by Albert J. Bergesen, Professor of Sociology at the University of Arizona. (You can read the essay in its entirety *here*.) To set the tone from Professor Bergesen’s essay, I have selected a quote from his introduction:

“. . . religion arises from experiences of grace, where something happens in human affairs that cannot be attributed to the normal workings of the world, hence suggesting the presence of a larger and more powerful presence, like God. Such grace experiences, which are sprinkled throughout life, are captured in symbols and passed down through the generations in story form, which would now include movies. But the process is more complicated, for not every kind of movie is comfortable with hints of God’s presence.”

“But the process is more complicated, for not every kind of movie is comfortable with hints of God’s presence.”

Professor Bergesen then proceeds to analyse a number of movies, all of which he purports have a spiritual or religious aspect. In ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’(wr. Arthur C. Clarke/dir. Stanley Kubrick), scientists discover evidence of aliens on the moon and a group of astronauts (including Keir Dullea and Gary Lockwood) are sent on a dangerous mission to investigate. In ‘Groundhog Day’(wr. Danny Rubin/dir. Harold Ramis), an arrogant weatherman (Bill Murray) is forced to repeat February 2 until he ‘gets it right’. In ‘Oh, God!’(wr. Larry Gelbart/dir. Carl Reiner), a dull supermarket manager (John Denver) encounters a little old man who claims to be God.

In ‘Field of Dreams’(wr./dir. Phil Alden Robinson), an (again) dull Iowa farmer (Kevin Costner) is instructed by a disembodied voice to build a baseball diamond in his corn field. In ‘Breaking the Waves’(wr./dir. Lars von Trier), a slow witted woman (Emily Watson) claims to speak regularly to God. In the first two of these films, which I classify as Science Fiction, God, if he is represented at all, is only implied. In the other three films, which I classify as fantasy, God is an overt presence. (A figure, a voice, or a beam of light that is clearly delineated on screen as representing the divine.)

If my interpretation of the essay is correct, Professor Bergesen is suggesting that the Science Fiction genre is not capable of dealing with spirituality unless you “break the form” as he suggests Stanley Kubrick did in ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’**. He states that, “To attain something extraordinary, … to hint at something spiritual or religious, requires violating the integrity of the science fiction premise. It is difficult to have hints of the supernatural intrude into films with a deep commitment to a believable everyday reality.” He also states that “The passive aggressiveness of science fiction would have absorbed any effort at hints of the extraordinary … because it is always possible that there is some natural thing out there that is the cause … the rest of the movie turns into a technical game of figuring out how this extraordinary experience is, in fact, part of the laws of some physics somewhere. (T)he conclusion isn’t that this is a hint of God’s presence, but that this is simply a world so advanced that we as yet don’t understand its operating principles.”

“How can anyone suspect God when it might be some alien force or some parallel universe or some cosmic time warp?”

But why is it outside the realm of possibility that the farmer in ‘Field of Dreams’ is hearing voices inside his own head because he might suffer from mild to severe schizophrenia? Why is it assumed to be the voice of God without any investigation? Is it not possible that the supermarket manager in ‘Oh, God!’ suffers from hallucinations? Would this not be the simplest explanation for these experiences, much further inside the realm of possibility than a physical manifestation of God would ever be. The reason that these dim-witted characters react with anger and dismay to a “reality not following its own rules” (as Professor Bergesen put it) is their ignorance. They are insular and conservative and do not have the tools to deal with something so far outside their experience, not unlike the ape-men at the beginning of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ who treat the monolith as a messenger from God because they haven’t the capacity to understand what they are looking at. Professor Bergesen states that “… since the characters can’t suspect (alien intervention) (every time something extraordinary happens), they are left with a hint of God.” He also poses the question “How can anyone suspect God when it might be some alien force or some parallel universe or some cosmic time warp?” If the Professor could only read his own statement in context, it shows pretty clearly that “suspecting God” is completely unnecessary.

The ‘Groundhog Day’ example used in Professor Bergensen’s essay can be used to counter the entire argument of the essay itself. The basic story of Groundhog Day is straight out of science fiction, and mimics an episode of the most famous science fiction television show ever broadcast, The Twilight Zone. (That series defined Science Fiction on television long before Star Trek came along.) Prof. Bergensen assumes it is his Judeo-Christian God that has caused the weatherman’s dilemma and that he is in some form of purgatory. But the movie never explains anything about the means by which the weatherman is stuck in time, which is why, to me, the movie seems to be nothing more than an extended episode of the Twilight Zone. The giveaway that ‘Groundhog Day’ is a Science Fiction story and not a religious story was that the weatherman used scientific experimentation to figure out the rules of his new reality. He figured out what those rules are and began to follow them, ultimately escaping his prison. It’s hard to find a more blatant example of the rational scientific method, exactly the same scientific method I would expect the scientist-astronaut in ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ would apply to his circumstance. But a technological explanation for the weatherman’s experience in ‘Groundhog Day’ would come only if you classified the film as Science Fiction and therefore his being “stuck in time” would have a technological, not a religious, explanation.

In the other films mentioned, there was an attempt by the filmmakers at anthropomorphizing God in the realm of the real, but it’s puzzling why this would lend any more credence or approachability to the existence of God. The single radio pulse to Jupiter in ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ could easily be equated with the sound of the bells at the end of ‘Breaking the Waves’, being no less ethereal and no less mysterious in its origins. How could the air be filled with the sounds of non-existent bells? The Iowa farmer in ‘Field of Dreams’ is a very similar character to the grocery store manager in ‘Oh, God!’. He purports to have been contacted by God and God told him (improbably) to build a baseball diamond in his corn field.

Easy. It’s God. How could an inert slab send a radio message to Jupiter? Easy. It’s God.Professor Bergesen writes that “Ray doesn’t suspect (aliens) either, nor his mental health.” Well, for starters, the possibility of mental illness never occurs to the mentally ill. (When I read the story line for that film, it was the first thing that occurred to me.) No self-respecting human being with an ounce of curiosity should simply accept these events as divine intervention, regardless of the genre of the film presenting them.

‘Field of Dreams’ brings to mind a news report many years ago where a woman in California was convinced that God was talking to her through her Walkman headphones. She had absolutely no doubt that it was God, and took it on faith that the voice on her headphones was from the “other side”. What she didn’t know, and what anyone with any knowledge of electronic devices knows, radio transmissions can resonate within electronic circuits. And what you could see on the report was a Christian Radio Station transmitting from across the street. So, I guess maybe God was talking to her, in a way, but it seems something less than a divine miracle to me.

I believe it is this supermarket manager in ‘Oh, God!’ who has the least credibility of all these characters. A relatively uneducated dim-wit, his only ambition is to get through the day so he can go home and watch television. Every miracle he witnesses is small and in scale to his everyday life, which only suggests that he has not the imagination to go outside his own experiences, even to find God. It is astounding to think that a charming old man in a ball cap doing magic tricks could be more mysterious to him than the entirety of space and time. But Professor Bergesen states that “(He) is shaken to the core and can’t believe what he is seeing.” Of course he is. A cell phone would have befuddled this guy. The problem with the story in ‘Oh, God!’ is that the manager suspects nothing else except that the little old man is God. It is a testament to his ignorance that he believes this old man is doing all this using no method what-so-ever. Any other rational human being would beg the question, “How was that done?”, and yet the manager is totally willing to accept the eccentric old man’s story without investigating it in any way. If the old man is making it rain in the car, then there are two possibilities: The rain is being created by some method (which can be investigated) or the rain is only inside the mind of the supermarket manager (which can also be investigated as a mental aberration). Again, the possibility of mental illness never occurs to the mentally ill.

Prof. Bergensen’s essay seems to ignore the fact that those scenes in space were revolutionary in their time . . .

In ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’, Heywood Floyd’s life is mundane in spite of the setting, and that makes him no different than the supermarket manager in some ways. The whole point of the banal scenes of Heywood Floyd traveling to the moon is to illustrate how disconnected modern people have become from the world they inhabit, and how any sense of awe is lost on them. But that sense of awe is not lost to the film’s audience. Prof. Bergensen’s essay seems to ignore the fact that those scenes in space were revolutionary in their time, in full frame ‘Ci-ne-ra-ma’, and at a time when virtually no one had ever seen what the Earth looked like from space. I’m sure if you had placed the supermarket manager into the same scenes, he would have been completely awestruck, maybe even as traumatized as he was when it rained inside his car.

And yet the world Dave Bowman and Heywood Floyd occupy is not a spiritual world. Using Prof. Bergensen’s criteria, would the supermarket manager not be obliged to assume that God created the space ship and the gadgets on board? Once he got used to it, the supermarket manager would be as bored with his life in space as he was at the supermarket, simply because he’s boring and incurious himself.

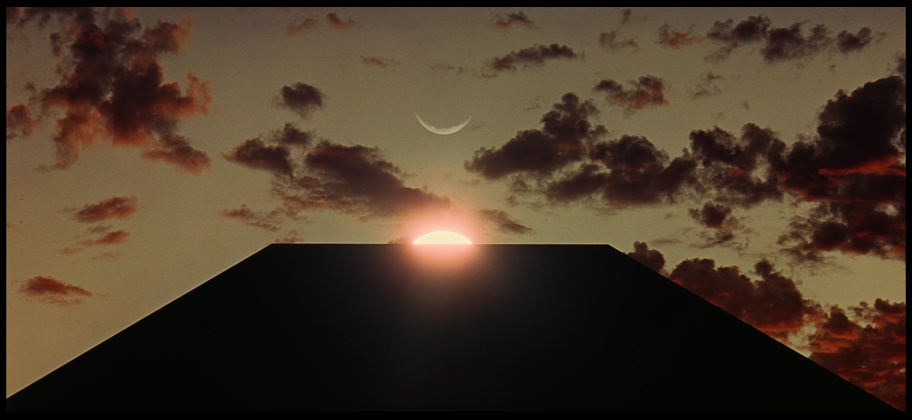

Prof. Bergesen presupposes the “difficulty in creating a sense of awe in science fiction”, and before ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’, he was probably correct to a certain extent. Before Stanley Kubrick took on the project, the technology of movie-making simply didn’t exist to portray such things with any sense of reality. Just the sheer scale of time in this movie is awe inspiring. And reflecting the experiences of the ape-men of the past with the space men of the future would do more to illustrate the scope of God’s will, if such a thing exists, than any overtly ‘religious’ movie with an anthropomorphic God ever could.

The essay seems to imply that if an astronaut found a black monolith on the moon, his first and only thought would be that it was a sign from God. It sends a radio signal to Jupiter? Again, a divine message the source of which is not worth investigating. This implies that our only obligation to such events would be to bow down and worship. Upon reflection, I’m sure the primitive minds of the apes would simply accept that the monolith was a God of some sort, but they hardly have the tools to investigate any other possibility. To the apes, the monolith was God. They never questioned it. It was unknowable. But I hope humans would have evolved significantly since then.

The world of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ is not populated by characters who are uneducated backward Hebrew hillbillies, schlubbing around the dusty streets of ancient Egypt, bowing down to every leaf that falls from a tree. These characters are scientists. Investigation is what they do. Professor Bergensen used lines like “They went to investigate as if it were a natural phenomenon.” His essay reports this like there should be some other way for normal people to react. Of course they investigated it. That’s why they went to Jupiter in the first place. Dave Bowman’s decision to investigate the monolith when he arrived at Jupiter was made years before he left Earth. What would you have him do, abandon his mission, saying that it is completely unknowable? Why would anyone think even for a moment that it was in any way “suicidal” as Prof. Bergensen suggested? The idea that “going off alone to certain death” has never occurred to the character of Bowman. He is a highly trained scientist who presumably studied and prepared for his mission for several years, was taught to expect anything, and when he did run across something he didn’t understand, learned to deal with it in a calm manner. That’s what astronauts do.

But even so, when he goes through the tunnel of light, he is as dismayed and confused as the Iowa farmer or the grocery store manager. He spends almost a full minute on screen in shock, eyes rolled back in his head. (Hardly the image of “calmness” reported by Bergensen.). In that elaborate, windowless hotel room (which is actually a recreation of a real hotel suite Stanley Kubrick had rented while living in New York) it is the first time since we met him that Bowman is struck with awe, forcing him to confront his own humanity, something his training had taken from him.

This “cut-out” character (as Bergensen suggests) shows more emotion here than at any other point in the film. Professor Bergesen states that “… the characters on the screen give no hint that they are in the presence of something divine or unaccountable.” He laments why Bowman’s character doesn’t run around asking an endless stream of redundant questions. He is speechless, not because reality isn’t “following the rules”, but that he doesn’t yet know what the rules are. Besides, he was alone. Who would he ask? The fact that Stanley Kubrick let the visuals tell the story (rather than the actor stating the obvious) is a testament to his skill as a filmmaker and not some shortcoming in his ability to depict the divine in his movie. After his initial shock on arriving at the hotel room, Bowman doesn’t know enough to be fearful. Everything was normal, he can breathe, he had plenty of fine food and nothing threatened him. And, as time passed, he settled in and accepted what he saw as his new reality. As with death, the transition was the shock, but what was on the other side was a world his mind could adapt to.

The fact that Stanley Kubrick let the visuals tell the story is a testament to his skill as a filmmaker and not some shortcoming in his ability to depict the divine in his movie.

The appearance of the monolith as Bowman dies of old age is the most overtly religious symbol in the film, implying this device was responsible for accelerating time around the character of Bowman. The black monolith was an obvious symbol of the undefinable, the unknowable that had come to take him into the unknown. He evolves, as the apes did at the beginning of the film. Kubrick was saying that it’s only after we survive our technological birth pangs that we will ever understand our universe.

Is the monolith God? The implication in Bergensen’s essay is “No”. But why not? Is it because the European Christian tradition only sees God as a human-like figure? Or a beam of light? And yet the entire hotel room is lit with what could be called ‘divine light’ from the glass floor. Why is this ‘light show’ not God, but the representations of God as light in the other films are accepted as such.

Mr. Bergensen’s essay presupposes that Kubrick tried (and failed) to illustrate a Judeo-Christian style God, which I don’t believe he had any intention of doing in the first place. The movie was written by Mr. Kubrick and Arthur C Clarke, two of the most intelligent men ever to work in film. Anyone who knows anything about Mr. Kubrick knows that the ending of the film, like all his films, is exactly what he intended. It is absurd to imply, as Prof. Bergensen has, that he was somehow stuck for an ending and tacked on this “collage” because he couldn’t think of anything else. It’s only Bergensen’s limited idea of the possibility of what could constitute God that causes such a thin critique of one of the most spiritual films ever made. The end sequence of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ is one of the most imaginative sequences ever placed on film, illustrating the long passage of time from the character’s arrival until his rebirth. Once the process begins, it becomes normal for Bowman, settling in until he gets some hint of what is actually happening to him, which happens when he is reborn as the Star Child. The montage (the proper term) is brilliant in how it realistically conveys how a person would actually react to something that they can’t comprehend.

The end sequence of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ is one of the most imaginative sequences ever placed on film . . .

Nothing shows the severe restrictions placed on God by the Judeo-Christian doctrine than when filmmakers try to use real imagery and sound to illustrate his/her presence. Many filmmakers take the easy way out, using the inevitable well-worn images that have been developed little since the ancient Hebrews walked away from their Egyptian overlords four or five thousand years ago.

God as a human figure has been around since before Moses, repeatedly being described has a having regular sized human-like body, with arms and legs. The reliance on the ‘little old man’ imagery has been in place since long before Michelangelo painted him on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. The imagery of sound and light has also been used since the beginning. Even films with explicitly Biblical subject matter have always had the same problem whenever an attempt is made to actually render these images in the non-poetic world. Religious epics have been produced since the beginning of cinema and, invariably, there is a human figure that represents God, waving his arms like an orchestra conductor as he makes “miraculous” events occur through obvious camera trickery. One hundred years or so later, to our eye, they seem like childish magic tricks. Whenever you present the “miraculous” events of the Bible in a real setting as described, there is no longer the sense of epic scale and Earth-shattering significance implied in the text. In fact, there’s very few of the miracles of the Bible that we can’t achieve today using technology. This inevitably come across as disappointing to say the least, a very long distance from the divine.

George Burns is undeniably adorable as God. (Though I do prefer Alanis Morissette or Audrey Hepburn, both having played God in movies and both being marginally more plausible than George Burns.) But any representation of God as a human being, whether in body or voice, hardly evokes the divine. And light as a representation of the divine, while amazing, is literally a daily occurrence by the very definition of ‘daily’. Such imagery is lazy, where the filmmakers choose to use the mundane to represent something that is, by definition, not prone to representation. The literal properties of filmmaking itself make spiritual imagery difficult to render, and show that any attempt to interpret the Bible literally is a fool’s errand.

The literal properties of filmmaking itself make spiritual imagery difficult to render, and show that any attempt to interpret the Bible literally is a fool’s errand.

In his essay, Professor Bergesen poses another question: “. . . the science fiction format, in naturalizing everything in its path, now leaves no room at the end of the movie for the intended spiritual, mystical, religious, or cosmic conclusions. (T)hen how does one put a hint of God in a movie?”

Well, the answer to that question is obvious: Spirituality is everywhere in Science Fiction, and has been part of its appeal since Mary Shelley invented the genre 200 years ago. Professor Bergensen is suggesting that the Science Fiction genre is too rigid to accept his narrow definition of God, but I believe that it is the Professor’s definition of God that is rigid, unable to encompass anything other than the images fed to him by his belief structure. On the one hand, he describes God as unknowable, and on the other, he retreats to the most obvious, small-minded characterizations of what a supreme being could be. Science Fiction refuses to simply bow down to the restrictive concept of God inherent in the Judeo-Christian tradition. Science Fiction challenges God to be something more sophisticated than the misogynist, violent, bipolar individual that was described in the ancient scriptures; an insular, spiteful God who spawned three equally hate-filled worldwide religions.

Science Fiction challenges God to be something more sophisticated than the misogynist, violent, bipolar individual that was described in the ancient scriptures . . .

But the biggest problem I have with Mr. Bergesen’s restrictive Judeo-Christian ideas of God is the problem of scale. These representations of God are invariably on an individual human scale. Much is made of a Jesus-like figure that effects the life of one individual, ignoring the plight of the other 7 billion people on the Earth. The unswerving faith of this one person (usually a man), who reports with childlike certainty that he will be ‘saved’ by some eternal force that follows none of the well established rules of the world, but no one else will. These ‘miracles’, a word that becomes ever increasingly harder to define as our knowledge of the universe increases, are only seen as such by the uneducated and ill-informed, and their faith is meant to trump every known fact that humanity has earned from hard experience since the species evolved.

Faith is willful ignorance and shows nothing of human spirit, human emotion and human intelligence, in fact diminishing all three. You cannot know the mind of God. Anyone who claims to know is wrong by default. But the “unknowable” God causes a problem for those like Prof. Bergensen, those who lack the imagination to go outside their restricted idea of God. You cannot have wars based on this kind of God. You cannot set political policy. It is, as defined, unknowable. If the only acceptable representations of God are at such a minute scale in relation to the universe as we now know it, then we have to concede that maybe the Jewish/Chistian/Islamic idea of God is narrow, misguided and just plain wrong. With regard to this small scale version of God, I like the idea that Carl Sagan put forward, that if you are not awed by the sheer size and complexity of the universe, then you are not reachable by God or anything else.

***

The foundations of Science Fiction were not abandoned at the end of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’, as Bergensen states. It is Science Fiction at its best. The mystery, the question being posed, is “What is the next step in the evolution of humanity?” And the obvious question that Mr. Kubrick is posing is exactly to whom we are asking this question? To God? To ourselves as a species? To our individuals selves? The monolith easily represents each of these questions far better than a little old man in a baseball cap. The spiritual metaphors in ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ beautifully illustrate how to introduce spirituality into a technologically rigid film, with the “unknowable” substituted for God. For me, the clear meaning of the ending of the film is that, eventually, we will understand the universe and our place in it. But we must first evolve.

Prof. Bergesen’s essay implies that willful ignorance is a prerequisite to spiritual awakening of any sort, and the moment rational investigation is applied, any chance of spiritual enlightenment is lost. But just because the universe is beyond our comprehension at present does not mean it is beyond all comprehension. If the next step in our evolution brings us to enlightenment, then the meaning of the Star Child at the end of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ will become clear. We have to evolve as a species, or we would still be scratching in the dirt like our primate ancestors at the beginning of the movie.

***

FOOTNOTES

* Published in a book of essays: “God in the Movies”, by Professor Albert J. Bergesen and Rev. Andrew M. Greeley, ISBN:0-7658-0020-9, (c.2000 Transaction Publishers)

** It is unfortunate that some of Professor Bergesen’s arguments are based on misremembered details of the film ‘2001: A Space Odyssey.’ Dr. Heywood Floyd, who Prof. Bergesen described as a scientist, is in fact a bureaucrat and has presumably been in space dozens of times, hence the banality of his behaviour there. (How many business class fliers, after years of flying, are awe struck by the view out their airplane window?) Also, the signal was sent to Jupiter by the monolith, it did not come from Jupiter. And when he arrives on the other side of the star-gate, Dave Bowman is in shock for a very long time, hardly the blasé attitude Prof. Bergesen implied in the essay. And there is no ‘marble floor’ in the rococo hotel suite, it is glass and lit from below. Finally, two versions of Bowman never appear on camera at the same time and he never “sees himself walking around” the suite.

1,379 total views, 1 views today