AI and the Hollywood Labour Strikes

***

“We’ll do all the things that … Robin Wright wouldn’t do.”

— Jeff (Danny Huston), The Congress

***

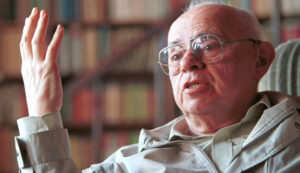

One of the more unusual aspects of the current labour disputes in Hollywood is the frequent reference to a little known (in America) science fiction writer from the cold war. The man in question is Ukrainian/Polish writer and philosopher Stanislaw Lem (1921-2006). Lem’s most famous work is Solaris (wr.1961), a science fiction masterpiece in which an astronaut must investigate a planet whose ocean exhibits conscious will over the scientists manning an orbiting research station. Solaris was so popular, it has been adapted for film three times; Solaris (1968) (wr. Nikolay Kemasky/dir. Boris Nirenburg), Solaris (1972) (wr. Friedrich Gorenstein/dir. Andrei Tarkovsky and Solaris (2002) (wr./dir. Steven Soderbergh).

At the time of his death in 2006, Lem had long given up on science fiction, focusing instead on his philosophical works. But before then, he had tallied more than two dozen novels and short-story compilations, most translated into dozens of languages. Seen as a science fiction visionary at the level of American novelist Philip K. Dick (especially by other sci-fi writers) he foresaw many things we now see as inevitable, including Artificial Intelligence, virtual reality, and the blending of truth and fiction.

Lem’s most obvious connection to the Hollywood strike is his 1971 satirical novel Kongres Futurologiczny (The Futurological Congress). After accidentally being exposed to an experimental psychoactive drug, the main character, Ijon Tichy, is thrown into a bizzaro world where everyone on the planet is under the influence of these synthetic drugs, making it nearly impossible for him to distinguish fantasy from reality. While the novel itself has no direct reference to artificial intelligence, the 2013 film adaptation of the book brought a different perspective to the story. That film, The Congress (wr./dir. Ari Folman) doesn’t cleave to the narrative of the book, with the writer/director suggesting it was more an inspiration than an adaptation. The film, a combination of live action and animation, shows (among other things) the consequences of performers losing control of their likeness and personality.

The focus of the conflict in The Congress is how technological advancement disrupts established norms, undermining the validity of legal contracts based on those norms. The problem usually comes when technology advances in unpredictable ways, sometimes benefiting the ‘owners’ over the ‘creators’; owners who find ever innovative ways to monetize their ‘intellectual property’. This has led to the ridiculous extreme of owners, whether individual or corporate, insisting on production contracts that allow them exclusive use of this intellectual property for the rest of all time in the universe. (Seriously.) Despite the clear contradiction to long-existing copyright laws, ‘in perpetuity’ clauses have existed for decades in Hollywood productions for understandable reasons, preventing a single performer or musician holding the producers hostage by tying them up in litigation every time a film was distributed, claiming rights to their image. But as technology advances, the concepts of ‘ownership’ and ‘authorship’ become increasingly slippery and ill-defined. The question then becomes: Do the original artists, despite their contracts, have any say in how their work is used in technological processes that were in no way conceivable when the contract was signed? And do they have any right to future profits from their work when new revenue streams are found?

The question then becomes: Do the original artists, despite their contracts, have any say in how their images are used in technological processes that were in no way conceivable when the contract was signed?

In the world of visual arts, the clear answer is no. Selling art for profit without compensation to the original artist is a tradition going back to pre-Roman times, and it wasn’t until modern times when anyone thought to question the practice. When collectors sell rare paintings or sculptures for millions of dollars, the original artists or their estates are in no way entitled to a cut of that profit, though there is a clear moral reason why they should. A commissioned work is traditionally the property of the one commissioning it, and they are usually responsible for its theme and subject matter. Edison didn’t invent the light bulb; he commissioned someone to invent the light bulb and took sole credit (and all the profit) for it. (1) A film can only be defined as a commissioned work but, unlike a light bulb, a film has no traditional mechanical function. Neither does a Rembrandt painting or a cathedral. Human endeavour has never been defined purely by the mechanical. No one credits Pope Julius II (1443-1513) for creating the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, though in the mindset of many film producers, they should.

No one credits Pope Julius II for creating the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, though in the mindset of many film producers, they should.

The introduction of ‘in perpetuity’ clauses on contracts was instigated for the very same reasons why actors and writers are periodically forced to organize a strike. The first major instance was the development of the re-run on television in the 1960s. Writers, directors and performers suddenly saw producers gaining almost endless advertising dollars by re-running their work over and over, with nothing compelling them to provide compensation to the creators. Feature film writers, directors and actors also found themselves out in the cold when producers ran movies endlessly on television, and eventually sold the rights of those films for video distribution. The major Hollywood strikes of 1960 and 1981 saw some remedy, providing residual payments to the artists whenever their work was licensed, though calculated by ever-diminishing percentages over time. The strikes showed artists were unwilling to stand for such technological loop holes in their contracts.

The advent of Artificial Intelligence takes the dangers of such exploitation one giant step further, allowing producers to take this kind of profiteering beyond anything seen so far. With no laws or precedent, it becomes the responsibility of the producers to protect the integrity of the performer and to reduce unfair enrichment. However, film producers in particular have a reputation for exploiting just such vagaries for exactly that purpose, making actors and writers justifiably wary of their motives. In the most egregious example, the cast of 1979’s Caligula (wr. Gore Vidal and Tinto Brass/dir. Tinto Brass) found this out the hard way. It’s certain that Malcolm McDowell, Sir Peter O’Toole, Dame Helen Mirren and Sir John Gielgud would never have agreed to appear in Caligula if they had known it would become a soft-core porn film in post production.

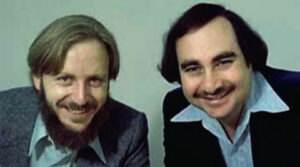

When Dan O’Bannon and Ron Shusett submitted the screenplay for Alien (wr. Dan O’ Bannon and Ron Shusett/dir. Ridley Scott) to the offices at Brandywine Productions, producers David Giler and Gordon Carroll knew they had something special on their desk. But that didn’t prevent them from feeling the need to ‘improve’ it in unimaginative ways, nor did it stop them from (badly) rewriting it and trying to claim credit for the idea. O’Bannon only discovered this by finding a copy of his script with his and Shusett’s name removed and replaced by those of the producers. In a ham-fisted attempt to make the characters ‘relatable’, the producer’s decided on a love story between Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) and Captain Dallas (Tom Skerrit), which was thankfully cut from the final script. The only significant thing the producers added to the story was, unsurprisingly, the story line about corporate intrigue by a robot spy. The Writer’s Guild of America agreed that Giler or Carroll had absolutely no claim for writing credit for Alien. (2)

But, in a weird way, this is what’s so inspiring about working in the film industry: Even the most black-hearted, tit-grabbing, money-grubbing producer is susceptible to optimism; dreaming of the day their genius for storytelling will be recognized around the world.

But, in a weird way, this is what’s so inspiring about working in the film industry: Even the most black-hearted, tit-grabbing, money-grubbing producer is susceptible to optimism; dreaming of the day their genius for storytelling will be recognized around the world. So much so they take full credit for any project in which they were even peripherally involved. Even a personal story ground out by a starving writer, whose realization was slaved over by directors, production designers and cinematographers, acted out with excruciatingly painful emotional fidelity by highly trained actors, whose performance is tuned to perfection by empathetic editors and composers, all can be denied credit by the people whose only significant contribution was to recognized the value of the enterprise and not get in the way of its creation. (3)

This is not to say that producers shouldn’t challenge their filmmakers, but there’s a very fine line between challenge and interference for the sake of ego. In the end, Alien, like Jaws (wr. Peter Benchley and Carl Gottlieb/dir. Seven Spielberg) was successful because of the extra effort by the director and the creative team, something which paid off handsomely for the producers, leading to a seemingly endless parade of sequels. At the time he filmed Alien, Ridley Scott was happy to admit a lot of the creative masterstrokes in that film were the result of budgetary and technical challenges more than pure inspiration. He and his crew were forced to be creative, making the movie much better for the effort. The decision not to show too much of the alien wasn’t some visionary flash but a practical one, in the same way that Steven Spielberg had to shoot around his relentlessly malfunctioning mechanical shark Bruce. The alien costume — like the shark in Jaws — didn’t look that great when seen from head to toe. As Scott said, “In the end, it’s just a bloke a rubber suit.” The unintended consequences of this was that much of the suspense in the movie is based on the fact that you can’t clearly see the creature, whether the shark or the alien. And like Jaws, this was the primary reason it was so terrifying.

Ridley Scott was happy to admit a lot of the creative masterstrokes in that film were the result of budgetary and technical challenges more than pure inspiration.

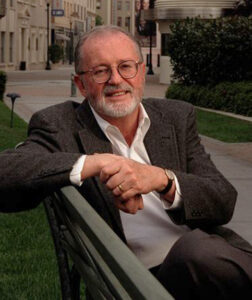

Don’t get me wrong, there are many producers who are well aware of who is responsible for content of a film, for better or worse. Brilliant producer and studio executive John Calley was responsible for a long list of very successful movies during the 1970s and 1980s, but nowhere will you see his name on a movie poster proclaiming credit for the success of the movie. Michael Kuhn was another, who took independent cinema to a whole new level supporting the likes of the Cohen Brothers, Danny Boyle and Terry Gilliam. (4) Jeffery Chernov is another, starting off producing Richard Pryor and Eddie Murphy’s live performances for film and becoming one of the biggest super-hero producers in Hollywood. Most of these producers understood that, when it comes to dealing with creative talent, it’s necessary to allow them creative leeway. It’s mystifying why some producers never learn that lesson, instead trying to turn creativity into the slave of faceless corporate profit and then punishing the creators when the audience rebels.

***

At first glance, it might not seem the SAG/AFTRA (or the Writers Guild of America (WGA)) are asking for anything more tangible than a salary increase. This perception of unrestrained greed is unfortunate but understandable. But when you actually look into it, you realize the vast majority of actors are not paid very much above their day rates, a pittance when compared with even mid-level professional athletes. But the rates of pay are far less important than the consistency. Sure, an actor might get thousands for dollars for a speaking role in a movie, but that doesn’t mean much since it now seems inevitable that technology will make those roles fewer and farther between.

The first major sign of the threat of Artificial Intelligence looming over Hollywood was Titanic (wr./dir James Cameron). Cameron populated the doomed ship with about three hundred digital extras, many of whom were played in performance capture by just a few actors who only got paid for a days work in a motion capture stage. Though it hardly holds up to the viewing standards of today, Titanic might have been justified in this case, since the ship was not built full scale. And, presumably, no one wanted three hundred extras plunging to their deaths in the North Atlantic (or off the coast of Mexico’s Baja to be more accurate). The money savings were staggering. Otherwise, the movie would have literally required legions of actors, a logistical nightmare that would have made the production unmanageable. This was exactly the kind of thing that tanked the movie studios in the 1960s with films like Cleopatra (wr. Ranald MacDougall and Sidney Buchman/dir. Joseph Mankiewicz) with its ‘cast of thousands’ and costing millions of dollars more than it made at the theatres.

Producers came to realize that this same capture data could be used over and over again for hundreds of characters, not only in that movie, but in whatever project that studio makes in the future.

Unfortunately, the most important take-away for the studios was in the scenes where the actors were not in peril, with Cameron choosing to populate even those scenes with virtual background performers. Producers came to realize that this same capture data could be used over and over again for hundreds of characters, not only in that movie, but in whatever project that studio makes in the future. And this goes for all the motion capture data created in all the productions in the past 25 years since Titanic. That’s thousands of performer-days lost to automation. And with AI, those performances can be enhanced and combined to produce virtually any actions at any speed or emotion, over and over again without any compensation to the performer who created it. In other words, some obscure background performer paid for those few days may now have to wait for eternity before their next gig.

Well, what does it matter really if a few extras have to quit the business for lack of work? It turns out, in the long term, it matters a great deal. The primary reason for the solidarity of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG/AFTRA) is that almost every well paid actor today remembers the time when they had to take a part-time job at Starbucks to pay the rent between gigs. Harrison Ford was working as a carpenter while paying his dues in bit parts like Colonel Lucas in Apocalypse Now (wr. John Milius and F. F. Coppola/ dir. Francis Ford Coppola). Another good example of this is Steve Buschemi, who became the king of bit parts before breaking out as Mr. Pink in Reservoir Dogs (wr./dir. Quentin Tarantino). (5) Work-a-day actors get progressively better parts as they get more exposure, something that will be lost if they never have to opportunity to get on set in the first place. Actors and background performers are facing a very different but equally real existential crisis and it could mean the pond of working actors is about to get very shallow indeed.

It could mean the pond of working actors is about to get very shallow indeed.

Actors understand that a performance is no different than any other creative endeavour, whether a painting or a song, a story or a sculpture. It’s a product of the artist and has to be treated as such. Theatre is a good example to take, where performances on any two nights are not the same, due to the dynamics between the performers on the stage. The theatre actor gets paid for each of those performances, not just the one perfected in rehearsals. If the original performers of the motion capture used in Titanic were paid in this way, they would be one of the best-paid supporting actors in Hollywood.

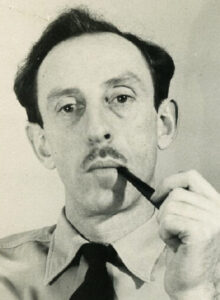

The next big leap after Titanic came with the Lord of the Rings Trilogy (wr. Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens, et.al./dir. Peter Jackson), taking us well beyond what was thought possible with the digital character of Gollum/Smeagol (played by Andy Serkis). Despite the realism of this character, it still depended on a real actor to perform it. Inevitably, though, these techniques were going to applied to real human actors, making ever-more ambitious attempts at spanning the ‘uncanny valley’. This culminated in 2016 with the release of Star Wars: Rogue One (wr. Chris Weitz and Tony Gilroy/dir. Gareth Edwards) where long-dead actor Peter Cushing (1913-1994) and the digital double of soon-to-be-dead Carrie Fisher (1956-2016) made creepy cameos.

This had been done before, of course, in movies like Play it Again Sam (wr. Woody Allen/dir. Herbert Ross) and Forest Gump (wr. Eric Roth/dir. Robert Zemeckis), where the likenesses of dead actors and historical figures were manipulated to have the actors say things they never actually said. But this was a laborious process of hand-drawn animation and digital manipulation of images done with the full cooperation of the estates of these celebrities. On the other side of that trend, public figures have been impersonated in film and on stage since the beginning of time. Ranging from parodies to sincere portrayals, everyone from Rich Little to ‘Weird Al’ Yankovic made lucrative careers out of it. It was rare for the celebrities or their estates to have any control over their impersonations in these situations, but their lack of fidelity made it unlikely anyone would mistake these imitators for the real thing.

And on the other side of this, public figures have been impersonated in film and on stage since the beginning of time.

It wasn’t until the reality of Artificial Intelligence began to force itself into the public eye that the long-term consequences of losing control of an individual’s likeness became a concern, especially with the advancement of ‘deep-fake’ videos that are becoming almost impossible to detect. The question of where the limits of public and private personas lie has never been made clear and the waters have only become more muddied as technology becomes more and more invasive of our private lives. It’s not hard to imagine what such technology could be used for in the hands of unscrupulous producers like Bob Guccione (1930-2010), who produced Caligula. The invasive nature of the unauthorized distribution of private images and video of celebrities can’t be overestimated, from the stolen sex-tape of Pamela Anderson to the hacking of phones by British tabloids. As a result, the steep learning curve for newly minted celebrities has become nightmarish.

***

In The Congress, Robin Wright’s body is scanned in medical detail and her entire life’s history is recorded, allowing the producers to create, with ultimate fidelity, an immortal digital version of the actress. Their stated intention is to continue and even enhance her career without the loathsome burden of aging, allowing audiences to forever experience the Robin Wright of Forest Gump and The Princess Bride (wr. William Goldman/dir. Rob Reiner). And, as quoted above, they would do all the things that Robin Wright, the human being, wouldn’t do.

She sees how this starts to become a personal violation of her own identity.

The result is that they manage to make her digital double a movie star beyond her wildest dreams, but at what price? Years later, she is given the opportunity to renegotiate her contract to allow her digital self to be transformed into a virtual reality avatar. Entering into this virtual reality using a proprietary drug, she finally sees all the potential abuses this could entail. Even though these violations would never actually happen to the person she has become since she was scanned many years before, she suddenly becomes aware of how much of a personal violation this is to her own identity. She questions whether the human reality of Robin Wright, with her solitary life, aging body and ailing son, was worth the price she was paid for her digital transformation. In the film, when the drugs cause her to lose track of reality, the digital fantasy becomes far more appealing. Faced with living in a dystopian world, she instead chooses to stay in the fantasy world, where she is perpetually young and is eventually reunited with her long-lost son. If only performers could look forward to such an outcome ‘in perpetuity’.

***

When the members of the Writer’s Guild of America voted to strike in May of this year, it wasn’t the first time they found themselves at the forefront of the labour dispute with the producers, and for a good reason. Of all the categories of employment in the film industry, writers are most under threat of being replaced by AI. Writers are rarely celebrated and usually long forgotten by the time a movie gets into the theatre or a television show is broadcast. If there is one consistency in film production it is the common desire for producers to bypass the need to employ writers.

At the beginning of every project, every producer is well aware that they are at the mercy of their writers. Even the lucky producers with the best intellectual property understand they do not have a film or a television show until there is a story to tell. Yes, financially successful movies have happened without a script. Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen (wr. Ehren Kruger, Roberto Orci and Alex Kurtzman/dir. Michael Bay) is famous for starting production during the 2008 writer’s strike with nothing more than a ten page outline. And, despite costing $200 million, it made back four times that. To say the wrong lesson was learned would be an understatement. That being said, no producer, not even Michael Bay, chooses to go into production without a serviceable script.

No producer, not even Michael Bay, chooses to go into production without a serviceable script.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not suggesting the producers are the only ones guilty of being hacks. If there has been one sickness in the Hollywood movie system it has to be the incredibly high rates of pay for cynically bad writers. (6) There’s the Hollywood truism that states that while hundreds of bad movies have been made from good scripts, there has never been a good movie made from a bad script and there are far more terrible movies made from bad scripts. Of course, no writer sets out to write a bad screenplay, just like no director sets out to direct a bad movie. But sometimes the well runs dry, and storytellers have to resort to questionable means to justify their position, cribbing ideas from obscure sources; changing a few words to make it their own.

Probably the most abused when it comes to this kind of cribbing is science fiction, a genre that is interesting mostly for its original ideas. It used to have the advantage of being relatively obscure, with little appeal to the general public. But the phenomenon of Star Wars (wr./dir. George Lucas) changed all that. While giving the original Star Wars its due (7), it is hardly a representative example of the depth of ideas science fiction has to offer.

While giving the original Star Wars its due, it is hardly a representative example of the depth of ideas science fiction has to offer.

Because of his international popularity and his relative obscurity in North America, Stanislaw Lem has been imitated and even plagiarized more often than most. Many would acknowledge Lem’s un-credited influence over the movie The Matrix, (wr./dir. Larry and Andy Wachowski, now Lana/Lilly), where the main character lives in an artificial internal world (much like the final chapters of The Futurological Congress) that masks the dystopian reality of the real world. (8) Ideas from Lem’s Pirx the Pilot books found their way into the hit movie series Pacific Rim (wr. Travis Beacham and G. Del Toro/dir. Guillermo del Toro). The clanking colossal robots with human operators inside are virtually identical to the industrial robots used by Pirx on the Saturnian moons. Authors like Edgar Rice Burroughs (John Carter of Mars, 1917) and Frank Herbert (Dune, 1965) have suffered the same fate, their works being picked so clean of ideas that it makes adaptations of their work almost impossible. John Carter (wr. Mark Andrews, Michael Chabon and Andrew Stanton/dir. Andrew Stanton) tanked at the box office, as did the original Dune (wr./dir. David Lynch), not because they weren’t interesting, but that they were perceived as being pale imitations of what had come before.

But science fiction is hardly the only genre ripe for this exploitation. A prime example is Nic Pizzolatto, the creator, writer and producer of the first season of the HBO series True Detective. The character Rust Cohle (played by the ever-greasy Matthew McConaughey) spouts dialogue that is almost verbatim taken from The Conspiracy Against the Human Race by nihilistic horror writer Thomas Ligotti, counting on the fact that the source was so obscure that his apparent plagiarism would go unnoticed. But with the internet, it didn’t take too long before he was exposed. Given HBO’s bank of copyright lawyers, Ligotti probably saw the futility of trying to argue the point in court, and no doubt the cost of such a fight would have bankrupted him. Fairness rarely triumphs in such cases.

Another famous example is author Alex Haley’s account of his ‘ancestry’ that resulted in the 1976 book and the ABC miniseries Roots (wr. Alex Haley and James Lee/dir. Marvin Chomsky, John Erman, et.al.). This ‘personal’ story of the legacy of African American slavery turned out to be a fictionalized account probably cribbed from the 1967 novel The African by the decidedly white anthropologist Harold Courlander.

And then there’s the untapped resource of foreign films. Other than the Matrix, the Kevin Spacey film KPax (wr. Charles Leavitt/dir. Iaia Softley) is probably one of the most egregious examples, having far too many similarities to the Argentinean film Hombre Mirando al Sudestem (wr./dir. Eliseo Subiela) to be coincidental. Guillermo del Toro’s Shape of Water (wr. Vanessa Taylor and G. Del Toro/dir. Guillermo del Toro) has striking similarities to the Soviet era Russian film Amphibian Man (wr. Alexandr Ksenofontov, Akiba Golburt and Aleksei Kapler/dir. Vladimir Chebotaryov and Gennadi Kasansky), making it difficult to accept his claim that he had never seen or even heard of the film. Also there’s Black Swan (wr. Mark Heyman, Andres Heinz and John McLaughlin/dir. Darren Aronofsky) having a suspicious similarity to the Japanese Manga film Perfect Blue (wr. Sadayuki Murai/dir Satoshi Kon). A comprehensive case list would go on for pages.

Of course there are situations where writers demand credit for something they clearly had no hand in creating. Famously, Harlan Ellison sued James Cameron for The Terminator (wr. Gale Anne Hurd/James Cameron/dir. James Cameron), claiming the idea as his own. The notoriously litigious Ellison insisted it too-closely resembled a story he created for the 1960s television drama The Outer Limits (cr. Leslie Stevens) called Soldier (wr. Harlan Ellison/dir. Gerd Oswald). Though sharing certain story elements, the actual stories are hardly the same. Much to Cameron’s dismay, the producers settled the claim in Ellison’s favour and to this day, he has a title credit at the end of the Terminator movies, acknowledging his alleged contribution.

In most cases, the courts have repeatedly found that you cannot copyright ‘ideas’, only their execution in a particular medium. No doubt a close examination of Ellison’s writing would find countless references and creative similarities to previous works. That’s no reflection on Harlan Ellison, it’s just the way creativity works. Ellison in no way ‘invented’ the idea of time travelling warriors, nor did he ‘invent’ the idea of a cyborg with a metal skeleton. I am normally all for writers getting credit where it is due, but this kind of legal underhandedness ends up stifling the creative output of every other writer for fear they might get sued if their idea even remotely resembles the IP of an entity with a few idle lawyers at hand.

No doubt a close examination of Ellison’s writing would find countless references and creative similarities to previous works.

Writers of television series are sometimes guilty of rehashing scripts from rival shows and conforming the story to their characters, sometimes with only a cursory attempt at disguising it. (9) Most shows have a bland similarity about them that lends them to this kind of pastiche, reworking old ideas using fresh faces. With the availability of many archives of series scripts online, it’s certainly easier today than ever to create a television show based on existing scripts. This practice has a lot to do with why people are so startled when they encounter true originality. With the rise of premium cable, there are only a limited number of true creatives to go around. It seems anyone with even a glimpse of success is showered with lots of money and attention, and then put into a creative meat grinder until they’re spent. And when this creative ‘genius’ eventually faces an empty page, he or she dreads the possibility that the well has run dry. And if the well does run dry, who could blame them for turning to chatGTP or some other AI systems for fresh ideas? Nothing wrong with that, as long as they’re using their own IP to generate those ideas. But if they started raiding other’s people’s IP, that’s when it gets contentious.

Pastiche, like forgery, is rightly seen as a form of fraud. It’s arguably the greatest insult you can impose on a creative writer. Which is why it’s startling to witness the naivety of the creators of AI experiments like chatGPT when they freely admit to using the intellectual property of thousands of creative artists to train their AI systems to imitate the creative process of those very artists, without getting permission or giving credit. Did they really think that world-renowned authors like Margret Atwood would stand still and allow them to use their creative output to enrich themselves? (10) If any human being worked this way, they would be rightly called out on it, or even prosecuted. It speaks volumes about the inflated self-importance of technology companies that they freely admit their unwillingness to adhere to long established laws of copyright.

Pastiche, like forgery, is rightly seen as a form of fraud. It’s arguably the greatest insult you can impose on a creative writer.

Film has been and always will be a hand-crafted medium, a bespoke creation of individual minds with a specific vision; with all parts of the process generated per spec, based on the individual creativity at all levels of the process. There might well be specific situations where AI could be used for creative work, but it’s inevitable such things would be familiar in all the wrong ways. Contrary to some opinions, there are few situations where off-the-shelf creative decisions could work. Movie productions still use lights created for the purpose, despite the fact that there are thousands of different lights available for use in the modern world. A corporate identity graphic can be created from a pastiche of real-world designs, but it takes the individual creativity of a Production Designer and a graphic artist to create a design that generates meaning within a story. Many would question why a filmmaker would ask for sets to be built when they could simply find a suitable location. More would question the need for costumes when real clothes would do. Some would question the need for a crane or a helicopter shot. Some (like Michael Bay) might even question the need for a writer. But, as you can imagine, such decisions make it less and less likely that anything of interest would come from the production.

When producers insist on such formulaic releases, the audience is very soon onto them. The reason that shows like Seinfeld (cr. Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld) was such a hit with audiences and critics was because the premise — ‘no hugging, no learning’ — was almost exactly counter to the usual sit-com formula. The writers made no effort to make the audience like the characters, who were in all petty and despicable. The show Rick and Morty (cr. Justin Roiland and Dan Harmon) has the same attitude, with every character at some point showing their self-centered attitude toward survival, a refreshingly honest approach hardly seen in today’s day and age. The writers on these series walk a fine line, sometimes verging on hate speech and sexism, between satire and offense. This kind of thing has not really been seen since the 1970s where standard family situations were turned on their head.

Shows like All in the Family (dev. Norman Lear), Fawlty Towers (cr. John Cleese and Connie Booth) and Sanford and Son (dev. Bud Yorkin). (11) It’s a revelation to watch some of the more over-the-top episodes of All in the Family. No one walked that tightrope better than Carroll O’Conner and Norman Lear, (except possibly Bea Arthur in Maude (cr. Norman Lear and Bud Yorkin).

Because of their originality, such television shows could never be created by Artificial Intelligence. Just like an AI system could never write a script for Alien because it doesn’t know what it’s like to be frightened. It couldn’t write The Big Lebowski (wr./dir. the Cohen Brothers) because it would have no idea why such a thing would be funny. Computers could never write The Breakfast Club (wr./dir. John Hughes) because they were never teenagers. AI could never write a screenplay for Showgirls (wr. Joe Eszterhas/dir. Paul Verhoeven) or Pink Flamingos (wr./dir. John Waters) because it could never understand sleaze and camp.

There is one thing that AI can never replicate and this might be the saving grace of writers and actors and any other creative person – sincerity.

There is one thing that might be the saving grace of writers and actors and any other creative person, something AI can never replicate – sincerity. No matter how advanced AI might become, it can never embody the sincerity of human experience. A pastiche could never induce such a thing. If there is one thing that movie goers can sense immediately is a filmmaker’s lack of sincerity. It’s why actors destroy their bodies for a role. It’s why designers work unpaid for hours into the night to get the details right. It’s why musicians labour over a single word or musical phrase. It’s why cinematographers spend hours and thousands of dollars to light a set properly. It’s why Teamsters get up at 3:00am to move the trucks to location. And it’s why writers distil the tragedy and joy of their lives into their stories.

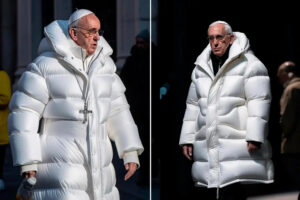

AI might be able to create an image of the Pope in a white puffy coat, but it didn’t create the coat, or the Papacy, or the medium of photography, nor did it instigate the need to create the image of the Pope in a puffy coat in the first place. It takes humans to do this because these things fill a human need. Without human input, AI cannot create anything. Any artist who has faced a blank canvass, any writer who has faced a blank page, any designer who has faced a blank stage, any actor who must create a character from scratch – every one of us knows the seeming impossibility of clearing that first hurtle; that of making the decision to create something from nothing.

AI might be able to create an image of the Pope in a white puffy coat, but it didn’t create the coat, or the Papacy, or the medium of photography, nor did it instigate the need to create the image of the Pope in a puffy coat in the first place. It takes humans to do this because these things fill a human need. Without human input, AI cannot create anything. Any artist who has faced a blank canvass, any writer who has faced a blank page, any designer who has faced a blank stage, any actor who must create a character from scratch – every one of us knows the seeming impossibility of clearing that first hurtle; that of making the decision to create something from nothing.

There is no doubt that AI will become the ultimate ‘bad Hollywood writer’ and there is nothing the Writer’s Guild of America and SAG/AFTRA can do about it. All AI writing encountered to date, while sometimes surprising, is nothing but pastiche, the cloying together of details of other stories with no regard for the creativity that produced them. And on the whole, they are usually pretty awful, requiring human writers to make them even slightly serviceable. The writers at the WGA have little to fear there.

There is no doubt that AI will become the ultimate ‘bad Hollywood writer’ and there is nothing the Writer’s Guild of America and SAG/AFTRA can do about it.

But the opposite is far more dangerous, where a serviceable script is distorted in order to strip credit from its creator, something AI is currently very good at, and getting better. Writers face the prospect of producers feeding their scripts through an AI system until all literal correspondence to their work is scrubbed away, allowing producers to claim writing credit and never having to pay writers residuals or even acknowledge their effort. Producers have to understand that teaching computers to cleverly steal from artists will effectively kill the process of creativity, effectively cooking the goose that lays golden eggs. And if the artists are not supported, then there is no one from which their IA can steal in the first place.

***

1. Actually, Edison bought the patent for his carbon filament light bulb from a pair of Canadian inventors, Matthew Evans and Henry Woodward (Patent #3738).

2. The problem was that, unlike O’Bannon and Shusett, neither producer had any experience or previous affinity for horror or science fiction. Steeped in decades of science fiction, O’Bannon and Shusett were able to pull elements from a number of sources including writer H.P. Lovecraft, a story from the 1951 edition of the Weird Science comic book called Seeds of Jupiter (wr. Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein) and a Roger Corman film called Queen of Blood (wr./dir. Curtis Harrington). In a stroke of genius, they based the alien’s morphology on the art of H.R. Geiger and the life cycle of parasitic wasps.)

3. My favourite credit on movie posters is ‘From the producers of –insert hit movie name here–!” Always with an exclamation mark! Well, I have to run and see that, no question.

4. Kuhn’s rise and fall role as head of Polygram Filmed Entertainment is documented in the brilliant documentary 100 Films and a Funeral (wr. Denis Sequin, Michael Kuhn and Michael McNamara/dir. Michael McNamara). He was largely responsible for the British film revival of the 1990’s.

5. I’m betting he didn’t make millions for his brilliant performance in Reservoir Dogs, but it led to cameo as the waiter ‘Buddy Holley’ in Pulp Fiction (wr./dir. Quentin Tarantino), getting him on set serving John Travolta and Uma Thurman. In the interim, he might well have been working as a real waiter. Who would have guessed he would become an Emmy Award winning character actor unless he was given the opportunity to be on set that day?

6. According to Wikipedia, the three writers of Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen were paid as much as six million dollars for their efforts.

7. Star Wars excelled at what it was, a pulp science fiction adventure film. Attempts since to try to impose any intellectual rigor to it or the rest of the series is an insult to what it aspired to be. It’s interesting that no such intellectual rigor has been applied to the equally pulpy Raiders of the Lost Ark (wr. Lawrence Kasdan/dir. Steven Speilberg) or the rest of the Indiana Jones franchise.

8. I’ve written before of how the Matrix movies had allegedly stolen so much material from Ghost in the Shell (wr. Kazunori Ito/dir. Mamoru Oshii) that the live-action remake (wr. Jamie Moss, Ehren Kruger and William Wheeler)/dir. Rupert Sanders) unfairly ended up looking like the imitator.

9. After 32 years in the film industry, I’ve personally witnessed writers for one television series rehashing scripts from another show. It’s unfortunately common practice.

10. And why has it become the responsibility of the writers to object to this? Don’t the publishers have just as much at stake, and just as much to lose?

11. Interesting that both All in the Family (based on ‘Til Death Do Us Part, cr. Johnny Speight), and Sanford and Son (based on Steptoe and Sons, cr. Ray Galton and Alan Simpson) were based on British television series. Fawlty Towers, of course, could never be made in America, even by the most right-minded tight-rope walker.

***

518 total views, 2 views today